Ukraine war: Tuva and Buryatia pay the highest price, but latest BBC Russian casualty figures show poverty not ethnicity the key factor

What do BBC Russian and Mediazona's latest Ukraine casualty figures tell us about which Russian regions and ethnic groups are sustaining the highest losses and why?

By Olga Ivshina.

BBC Russian and Mediazona’s ongoing count of confirmed Russian casualty figures in Ukraine has now reached almost 40,000 names. A breakdown of the numbers reveals that Tuva and Buryatia are the regions sustaining the highest proportionate rate of casualties, but it’s poverty and not ethnicity that’s the key factor at play.

On 7 June this year, a poignant post appeared on a social media page dedicated to the memory of fallen serviceman in the Republic of Tuva.

It announced the death of 54-year old Alima Lopsanei a much-loved mother and grandmother who passed away just four days after burying her son Aidash, 28 who was killed fighting in Ukraine.

"Alima Bolat-oolovna's heart couldn't bear it,” the post said. “She couldn't come to terms with the death of her only son."

Alima’s son was just one of hundreds of young men from Tuva, and the neighbouring Republic of Buryatia, to die in Ukraine this year.

These are some of Russia’s poorest regions: places where many young men see the army as their only chance to earn a decent living. And it’s these places that are now paying a disproportionately high price as Russian war casualties continue to rise.

November toll

Since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, BBC News Russian has been working with the independent news outlet Mediazona, and a group of volunteers to keep a count of Russia’s war dead based on open source information.

As of the end of November, our count has reached 37, 686 confirmed names.

The actual number is of course much higher as many deaths are not announced or acknowledged publicly.

We asked Alexey Bessudnov a sociologist from the University of Exeter, to look at our data and try to draw some conclusions about who is being killed and which Russian regions are most affected.

Regional differences

At first glance it’s clear that in terms of the absolute number of deaths, the regions with the highest losses are Krasnodar Krai, Sverdlovsk Oblast, Bashkortostan, and Chelyabinsk Oblast.

However, when we compared the number of deaths with the number of men aged between 16 and 61 living in each region, a more nuanced picture emerged.

We looked at how many military deaths each region had sustained for every 10,000 men living there.

Using this calculation Tuva emerges as the region with highest number of deaths - 48.6, followed by Buryatia (36.7), the Nenets Autonomous Okrug (30), the Altai Republic (26.5), and Zabaykalsky Krai (26.2).

By comparison, St. Petersburg has 2.5 deaths for every 10,000 men, and Moscow has just one. So if you are a man of military age, living in Russia’s two biggest cities, your chances of being killed in Ukraine are ten times lower than for your contemporaries living in Siberia and the Far East.

"A significant portion of the losses falls on predominantly poor regions experiencing a shortage of natural resources," says Alexey Bessudnov in his paper “Ethnic and regional inequalities in the Russian military fatalities in Ukraine: Preliminary findings from crowdsourced data”, which he wrote analysing our data.

Tatarstan, with its developed oil industry, shows a significantly lower number of losses per capita compared to economically less developed regions like Buryatia, Tuva, Altai, and North Ossetia.

One exception to this rule is the Nenets Autonomous Okrug which has a thriving oil extraction industry, but nonetheless still has very high death rates per 10,000 men.

In a recent interview with the ‘People of Baikal’ news site, Buryat activist and researcher Maria Vyushkova, now based at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, said the reason for this apparent discrepancy was simple:

“The oil industry doesn't bring anything to the indigenous population. On the contrary, it destroys the environment and what they live on - reindeer herding and fishing. Consequently, being in a dire economic situation, people are forced to join the army."

Ethnic divide

Calculating how many soldiers are being killed for every 10,000 men gives a sense of the overall cost of the war to individual regions, but it doesn’t tell us which ethnic groups are sustaining the highest casualty levels.

The proportion of ethnic Russians in different regions and republics varies considerably, so a region sustaining high losses does not necessarily mean that the titular ethnic group in that area is hit hardest.

In Buryatia, about 60% of young men are ethnically Russian, while in Tuva, the proportion of Russians is around 10%, and in Chechnya and Ingushetia, it's less than 1%.

One way to try to understand more about the casualty levels being sustained by different ethnic groups, is to look at the names and surnames of soldiers killed in action.

Of course this isn’t always a 100 per cent reliable indicator. Some ethnic groups like the Chuvash and Komi peoples tend to have Russified last names, and ethnic identity is obviously not just determined by people’s names.

But Aleksey Bessudnov at Exeter University has developed an algorithm to give approximate estimates based on the names on casualty lists, and by doing so he has been able to confirm some assumptions about who is fighting and dying in Ukraine.

The first notable trend is that the majority of soldiers who have been killed in Ukraine are Slavs - and primarily ethnic Russians. The number of ethnic Russians in casualty lists more or less matches the overall proportion of ethnic Russians as opposed to other national groups in the male population of the Russian Federation.

It's challenging to conduct a more detailed breakdown here because based on information from names and surnames, it's difficult to distinguish Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians: many Ukrainians have Russian-origin surnames, and vice versa.

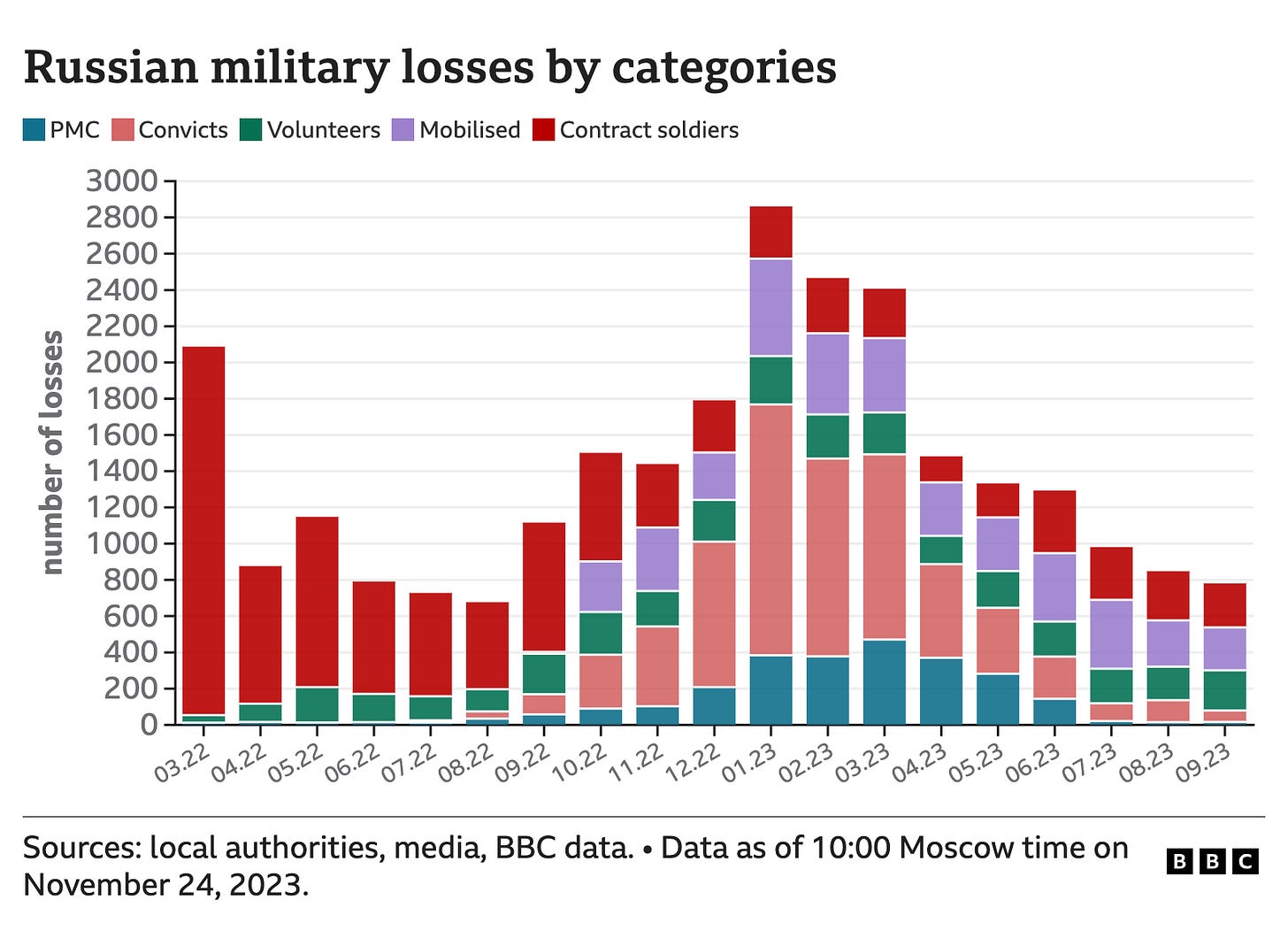

As the war continues, the percentage of Slav names among the dead is increasing. In the spring 2022, it was at 75%, and a year later, it rose to 85%. Researchers attribute this to mobilization and the enlistment of prisoners to the front lines.

The second trend Bessudnov has been able to shed more light on is that while Buryats and Tuvans are clearly dying in disproportionate numbers compared to their share of the overall population, the numbers of young men from the two regions being killed as a percentage of the overall casualty figures is gradually decreasing as more ethnic Russians sign up to fight.

This decline is also particularly noticeable in the North Caucasus, where Bessudnov notes that the percentage of men being killed has fallen from 11 per cent of the total to two per cent.

So as the war grinds on it seems that what’s really at stake here, is not ethnicity but socio-economic status.

What’s happening in the Russian army, mirrors the situation in the US army in Vietnam, Korea and Iraq, where young men from poorer states and disadvantaged communities were more likely to join the army and thus more likely to be killed in action.

It’s clear to see from the casualty figures that most of the Russian soldiers fighting and dying in Ukraine are men from the periphery - from small towns and villages all over Russia.

Whether you are from Buryatia, or Chelyabinsk Oblast, you have fewer opportunities to find a stable job than someone from a big city, so there’s a bigger chance that you will join the army, and consequently there’s a bigger risk of getting killed in Ukraine.

And if you compare how many ethnic Buryat or Tuva soldiers are being killed in Ukraine, compared to ethnic Russians from Buryatia or Tuva, then the difference is “statistically insignificant”, says Aleksey Bessudnov.

Since the start of the war in Ukraine, BBC Russian has been working with Mediazona, and a group of volunteers to keep a count of Russia’s war dead. We use open source information - the media, social media posts and cemetery records.

Read this story in Russian here.

Read an overview of the project in English here.