LONG READ - Prison, war and revenge killing: the inside story of the Wagner ‘sledgehammer murder’ case

The story of the life and death of Yevgeny Nuzhin is a grim illustration of how Russia is increasingly using its prison population as a source of new blood on the deadly frontline in Ukraine.

By Elizaveta Fokht and Anastasia Lotareva.

In the summer of 2022 a Russian prison inmate serving a 28-year sentence for murder, volunteered to go to fight in Ukraine. He ended up dead, but not on the battlefield. The story of the life and death of Yevgeny Nuzhin, a killer, a mercenary, but also a husband, father and grandfather, is a grim illustration of how Russia is increasingly using its prison population as an expendable source of new blood on the deadly frontline in eastern Ukraine.

This is an updated version of an award-winning BBC Russian story first published on November 17, 2022.

Warning: the text contains descriptions of violence.

The last time Ilya and Nikita Nuzhin spoke to their father Yevgeny was on a video call from prison in August 2022. Nuzhin senior had been in jail since 1999, serving a 28-year sentence for murder, and this was the family’s main means of communication.

Yevgeny seemed scared and lost, says Nikita’s wife Anastasia, who agreed to speak to the BBC on behalf of the family. He said a recruiter from the Wagner Group private military company had visited the prison, and he had decided to join up to fight in Ukraine.

“All his relatives were against it," Anastasia remembers. "His wife was crying. But he said: no, I’m going anyway.”

Although the family didn’t know it at the time, Nuzhin was about to become one of thousands of serving Russian prisoners who would volunteer to join the Wagner Group, and risk all in the hope of a pardon in exchange for fighting on the frontline.

In the four months since that family video call, BBC Russian has been able to confirm the deaths of at least 240 serving prisoners killed fighting in Ukraine. What was initially a secretive recruitment process, is now something that is openly acknowledged at the highest level in Russia.

But it was the story of the life and eventual terrible death of Yevgeny Nuzhin that first brought the issue into the open and was to become a symbol of the grim fate awaiting so many of these new volunteers.

The road to prison colony number 3

Yevgeny Nuzhin was born in Kazakhstan in 1967. As a child he and his parents moved to Russia, where he grew up, did his compulsary military service, and then stayed on serving with the interior troops, until 1995. He then settled in Nizhny Novgorod, where he got married and had a family of his own.

In the lawless 1990s, as organised crime took hold across many parts of Russia, Nuzhin was involved in a shoot-out which left one man dead and another injured. “It was a case of either I shoot them or they shoot me”, he said later. In 1999 he was found guilty of murder and given a 24-year prison sentence.

He spent time in various prison camps, including a high-security penal colony in the Northern Urals, where after a failed escape attempt his sentence was increased by four years, meaning he was not due for release until 2027.

By 2009 Nuzhin had been moved to prison colony number 3 in the town of Skopin, in Ryazan Oblast, which housed many former Interior Ministry employees.

Anastasia Nuzhina says conditions in the prison were good and her father-in-law “lived very well” and was respected by fellow inmates.

He was also able to get access to a tablet and phone, which not only made communications with his family easier, but also enabled him to get online and find out more about the world outside his prison walls.

He opened accounts on VKontakte – the Russian equivalent of Facebook. It was here he later posted photos of his wedding to his second wife Olga, who he met online and married in the prison chapel, in a ceremony complete with Orthodox wedding crowns and candles.

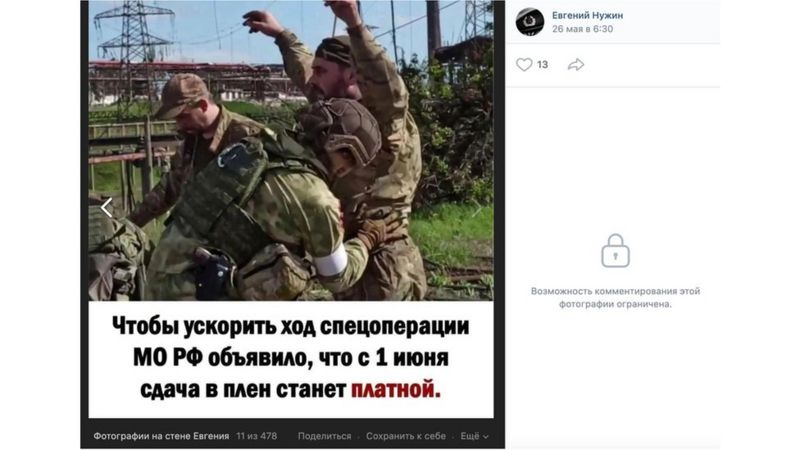

Nuzhin’s social media accounts are still accessible and offer a window into his life and mindset before he decided to join the Wagner group.

Along with the wedding photos are posts about his family – his two sons, Ilya and Nikita, who he refers to as his “Eagles” and his wife –“My love”. There are also quotes about resilience of the Russian spirit and Orthodoxy, and Imperial flags alongside nostalgic photos of the Soviet past.

Nuzhin made very little reference on social media to either politics or the war in Ukraine. In May he reposted a video of a Catholic priest in Poland praising Putin for his ability to withstand the ‘world government’ and discussing Ukraine’s ‘denazification’. He also reposted a couple of images containing ironic comments about the ‘special military operation’ and criticizing some Russian MPs.

In short there was nothing to indicate that Nuzhin had any strong views either for or against the war in Ukraine, and nothing that might help his family understand why someone with just four years left to serve of a 28-year sentence, would volunteer to go to war. For that, the Nuzhin family had to wait until the next time they would see their father on camera – in a series of videos recorded after he was captured in Ukraine. And even then, what he had to say would raise more questions than answers.

The first interview

Ukrainian war correspondent Bohdan Papadin was on an assignment in Donetsk region in early September when he got a call one night from a contact in the Ukrainian army asking if he would be interested in interviewing a Russian POW.

The man was a fighter from the Wagner military group who’d been captured near the town of Soledar, and wanted to tell his story to the media.

Broadcasting interviews with POWs is prohibited by the Geneva Conventions, but despite this many captured Russian soldiers have appeared on camera in Ukraine speaking about their experiences. While it is impossible to know if they are speaking freely, it’s clear that many have used the opportunity to let their families know they are still alive.

Papadin had already filmed several interviews with Russian POWs, but never with a Wagner fighter.

“The Russians don’t usually want to take back Wagner fighters in prisoner exchanges”, he said. “And they don’t have any interesting information, anyway.”

He agreed to film the interview and was taken to a village where the prisoner was being held in the basement of a house.

The man, dressed in military fatigues and sitting on a red striped mattress, introduced himself as Yevgeny Nuzhin. He appeared well treated, says Papadin, but what was most striking about him was how calm he was.

It was a big contrast to the POWs he had previously encountered all of whom had had what he describes as “some sort of animal fear in their eyes from not knowing what would happen to them next”.

Papadin set up his camera and over the course of the next half hour a clearly exhausted Yevgeny Nuzhin spoke in detail about himself and how he had ended up on the frontline in Ukraine. Papadin shared the footage with a popular Ukrainian YouTube channel Butusov Plus where it was uploaded in full, on 15 September.

We love you dad

Nuzhin’s interview attracted a huge amount of attention in Russia. Among the hundreds of thousands who watched it were his family back home in Nizhny Novgorod.

It was the first news they’d had of him since the video chat in August, and for them it was confirmation at least, that he was still alive.

Anastasia Nuzhina says the family frantically contacted the authorities to try to find out more. But they hit a brick wall.

The Russian Defence Ministry told them it wasn’t a matter for them because he was a serving prisoner. The prison colony in Skopin where Nuzhin had been serving his sentence said they couldn’t help. The Red Cross had no information.

In desperation Anastasia started posting messages for her father-in-law on the Butusov live YouTube channel.

“Dad we all love you and we’re waiting for you,” she wrote. “We’re so worried about you. Hang in there however long it takes. We’re all praying for you. Your grandchildren are asking when grandad is coming back. We don’t judge you for anything. Hold on, that’s the main thing. You’ve been through so much, and you just need to keep going for a little bit longer, Dad. Your daughter-in-law, Nastya.”

‘The Motherland is in danger’

The story Nuzhin told to Bohdan Papadin described how the system for recruiting prisoners worked.

Back in July 2022, he said, a helicopter had landed on open ground next to the prison colony. The prisoners were lined up in the square, and out came Yevgeny Prigozhin, the St Petersburg businessman and close associate of President Putin, who heads the Wagner group. He was wearing a ‘Hero of Russia’ medal. “The Motherland is in danger,” he told them, offering them the chance of a big salary and a pardon if they volunteered to go and fight in Ukraine.

Nuzhin was one of 92 people who signed up on the spot. A month later, Prigozhin returned and on 25 August the volunteers were transported to an airbase near Rostov before being flown by helicopter to Luhansk region.

In his interview with Papadin, Nuzhin claimed that the real reason he had joined up was because he sympathised with Ukraine.

"I wanted to fight on the Ukrainian side — that's why I surrendered,” he said. “I made my decision a long time ago, while I was still in prison. Because it wasn’t Ukraine that attacked Russia — it was Putin who attacked Ukraine,"

He said he had watched lots of Ukrainian bloggers on YouTube and had formed a plan to join a legion of Russian volunteers fighting on the Ukrainian side.

He also told Papadin that he had family in Ukraine – an uncle in Ivano-Frankivsk, and a sister and niece in Lviv. “How can I fight against you when I have relatives here?” he said.

Nuzhin's son Nikita was quoted by the Russian independent media outlet Holod as saying his father had told him privately that he was against the war in Ukraine. But Anastasia, his daughter-in-law takes a more sceptical view.

"A man who was in prison for 23 years suddenly went and agreed to something like that? He had four years left to serve, a tiny proportion of the time he’d already spent there... Either he was tricked, or I don't know what happened."

Filling in the blanks

From the Butusov Live interview, and from subsequent conversations on camera with other reporters the Nuzhin family were able to fill in some of the blanks about what had happened to their father after he left prison.

At the Wagner base in Luhansk, he told Bohdan Papadin, he and his fellow inmate-volunteers were given ‘a stack of papers” to sign. They were issued with kit and AK-74 rifles and spent a week doing basic military training before being transferred to a frontline area on 2 September.

Discipline in the Wagner group was brutal, he said, with new recruits made to understand that: “If you don’t do what you’re told, they shoot you.”

Nuzhin was assigned to the 7th Assault Squad.

“What was the purpose of these assault squads?” Papadin asked him. “As far as I could understand it, we were just cannon fodder,” Nuzhin replied.

Nuzhin said he was part of a group of 17 convicts assigned to retrieve the bodies of soldiers killed on the frontline. On 4 September they were driven to a wooded area and made their way on foot to trenches from where they were told to head out under cover of darkness to look for dead bodies. In the confusion that followed, Nuzhin said that he managed to get away from others and headed for the Ukrainian side to surrender.

As the weeks went by, there were other interviews in other locations. At one stage he even spoke to the New York Times, although the paper did not publish anything. In each video Nuzhin looked clean and well cared for and seemed to be in good spirits.

In one, Ukrainian journalist Ramina Eshakzai read out the YouTube messages Anastasia had left for her father-in-law. A tearful Nuzhin called on his sons, and other Russian prisoners not to go to war.

He told Eshakzai that he was still hoping he would be able to join up to fight for Ukraine. “I’d like to do at least something against Putin, in sum, to do something worthwhile in this life," he said.

In another video on 1 November on the Butusov live channel a smiling Nuzhin sent greetings to his family, telling them ‘everything will be alright’.

All this gave Anastasia and the rest of the family some cause for hope.

But those hopes were soon to be dashed.

The hammer of revenge

On the night of 13 November, a video was posted on Grey Zone, a Russian Telegram channel linked to the Wagner group. It was called ‘The Hammer of Revenge’.

The video begins with clips from Nuzhin's Ukrainian YouTube interviews, in which he can be heard saying he surrendered voluntarily to fight for Ukraine. Then he appears in the frame, lying on his side. A bright light is shining in his face, and his head is taped to a stone block.

"I, Yevgeny Anatolyevich Nuzhin, born in 1967, went to the frontline with the aim of switching sides and fighting against the Russians.,” he says. “On September 4, I carried out my plan and crossed to the Ukrainian side. On November 11, 2022, on a street in Kyiv, I received a blow to the head and lost consciousness. I woke up in this cellar where I was told that I would be tried.”

Then a person in the background smashes a sledgehammer into Nuzhin’s head and kills him.

Two versions of the video were posted on social media. In the first, the last few seconds have been blurred out. In the second they have not. The video ends with a caption calling Nuzhin a traitor who "received the traditional primordial Wagnerian punishment."

Although it has never been independently verified, the video is widely believed to be genuine.

The video made headlines around the world, prompting many expressions of shock and revulsion. It also raised many questions for both the Russian and Ukrainian sides.

Had the Wagner Group really executed one of their own fighters on camera? What were the Russian law enforcement authorities going to do about it? And how did someone who was being held as a POW in Ukraine, and who had been allowed to publicly voice his opposition to Putin’s war, end up back in Russia?

Two months on from Nuzhin’s murder, many of these questions have still not been fully answered.

Bravado, defiance and silence

Yevgeny Prigozhin responded to Nuzhin’s murder with his now trademark mixture of bravado and defiance.

The day after the video appeared his press service issued a statement calling it “excellent directorial work", and suggesting a better title for it would be “a dog’s death for a dog”.

He went on to write to the Russian Prosecutor General Igor Krasnov calling for an investigation into the case and sharing his own intentionally implausible version of events, suggesting Nuzhin was CIA spy and had been kidnapped and killed by "US intelligence agencies".

And to further underline his contempt for the case, at the end of November Prigozhin’s press service reported he had sent a sledgehammer with the Wagner logo, covered in fake blood and packed in a violin case to contacts in Brussels for onward presentation to the European Parliament after the EU put the Wagner group on its terrorist list.

People close to the Wagner group, have told BBC Russian (on condition of anonymity) they are not surprised by the Nuzhin video, and they know of at least three similar cases of violent reprisal killings. None of these incidents have been made public, and the BBC is unable to confirm the details.

But one earlier killing involving Wagner fighters did make the news. In 2017 a group of Wagner fighters in Syria filmed themselves killing a Syrian army deserter with a sledgehammer and then dismembering and setting fire to his body. The incident was reported in detail by the Novaya Gazeta newspaper in 2019. The perpetrators were identified and the victim’s family supported by human rights groups tried to get the Russian courts to prosecute them. Appeals were lodged with the head of the Investigative Committee, Aleksandr Bastrykin, but the case was never pursued.

Mr Bastrykin has been similarly unresponsive to the Nuzhin case.

He ignored a call from Russia’s Human Rights Council on 14 November, to look into the circumstances around Nuzhin’s death and in particular what the legal ramifications were of the apparent murder of someone still technically the responsibility of the Russian prison system.

Neither Mr Bastrykin, the Investigative Committee or the Russian Prosecutor’s office responded to requests for comment from the BBC.

President Putin’s press spokesman Dmitry Peskov told journalists the Kremlin had no comment to make about the video. "It's not our business," he said.

‘What Russians do to Russians is not our problem’

On the Ukrainian side officials have been less reticent, but statements about the case have often been contradictory.

Official Ukrainian policy is that no Russians who voluntarily surrender should be forced to return home. Early on in the conflict a special ‘I Want to Live’ hotline was set up to give advice to soldiers wanting to lay down their weapons. Ukrainian officials, including President Zelensky have repeatedly stressed that POWs will be treated humanely under the terms of the Geneva Conventions.

So was Nuzhin returned to Russia as part of an official prisoner exchange, and if so, did he agree to be sent back?

In the immediate aftermath of the video appearing it was clear that there was much confusion over his status as a serving prisoner and Wagner Group mercenary, and whether this legally entitled him to the same treatment as regular soldiers.

On 15 November Ukraine’s Coordination Headquarters for the treatment of prisoners of war – part of the Intelligence Directorate of the Defence Ministry, issued a statement about the case, saying Nuzhin had not been on the list of captives "who surrendered voluntarily".

"Nuzhin was serving a sentence for a serious crime in a penal colony of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs,” the statement read. “To get out of prison, he agreed to participate as a mercenary in Russia's war against Ukraine, was on our country’s territory as a member of the abhorrent Wagner group, and before the war was a supporter of the policy of the aggressor state.”

However, in an interview with the BBC at the end of November Ukrainian presidential aide Mykhailo Podolyak sought to clarify the situation, saying Ukraine did not distinguish between people fighting for private military companies like Wagner, and the regular Russian army.

“To us they are all combatants and the conventions applied to prisoners of war cover all of them.”

Podolyak told the BBC that prisoner exchanges were negotiated by the Ukrainian Intelligence Directorate with the involvement on the Russian side of the Defence Ministry, the General Prosecutors Office and the Investigations Committee. He said it was his understanding that Nuzhin had agreed to be returned to Russia as part of a regular prisoner swap.

“As far as I know, Nuzhin went through all the correct procedures and was exchanged through the framework of a voluntary exchange agreement,” he said.

Podolyak suggested that the BBC ask the Intelligence Directorate for further clarification.

No response has been forthcoming.

Just two days before the video of Nuzhin’s murder emerged, the head of Ukrainian president’s office, Andriy Yermak announced that a regular prisoner swap had successfully taken place and that 45 military personnel had been brought home.

There was no official confirmation from the Russian side. It’s not known how many Russian POWs were returned, and no evidence has emerged so far to suggest that Yevgeny Nuzhin was one of them.

However the pro-Kremlin blogger Anastasia Kashevarova claimed that the prisoner swap had taken place with the involvement of the Wagner group, who she said “had their own exchange pool”.

A source in Kyiv, with close knowledge of prisoner swap negotiations told BBC Russian that the Wagner group did indeed sometimes take part in exchange talks.

Speaking on condition of anonymity the source said the Wagner chief, Yevgeny Prigozhin had previously succeeded in negotiating the return of five of his captured soldiers in exchange for the bodies of Ukrainians killed in action.

In Nuzhin’s case, the source claimed that Wagner had offered ‘very good terms’ for his return to Russia.

There has been no official information about what these terms might have included. But in days after the video emerged, many commentators in Ukraine, including Ramina Eshakzai, one of the journalists who interviewed him in captivity, and presidential advisor Olexiy Arestovich referred to “twenty” Ukrainian servicemen being freed in exchange for Nuzhin.

Asked by the BBC to comment on Nuzhin’s subsequent fate, the source close to the negotiations said Ukraine’s first priority was always the return of its own personnel.

"What Russians do to another Russian – that’s your Russian problem," the source said.

But the murder of Yevgeny Nuzhin does seem to have given some Ukrainian officials pause for thought.

Presidential advisor Mykhailo Podolyak told the BBC that he did not think any “catastrophic” mistakes had been made in the way the case was handled, but acknowledged that strategy, tactics and communications were inevitably subject to “correction” as the war progressed.

“Of course, some incidents – and not just the incident with Nuzhin, but others too, change our understanding of how Russia reacts, how the world reacts to some of our initiatives,” he said. “And of course, we make corrections.”

Were there lessons to be learned from the case, the BBC asked.

“We are good at learning lessons,” Podolyak replied.

Hoping for a decent burial

Back in Russia, Yevgeny Nuzhin’s family are still in shock about their father’s death.

They found out about it the same way as everyone else, by seeing the video on social media.

His wife Olga, couldn’t bring herself to watch it to the end, says daughter-in-law. Anastasia. “She just cries all the time.”

Olga tried calling the prison where her husband had been serving his sentence, but to no avail. After the video they stopped returning her calls, says Anastasia, and eventually they just blocked her number.

No-one from either the police or the Investigative Committee has been in touch. The FSB made one call to a family member asking about Nuzhin’s sons Ilya and Nikita. But the brothers didn’t respond, fearing for their safety.

"We are under a lot of pressure from the outside," says Anastasia. "People are divided 50/50. Some say we should all be killed, others offer their condolences.”

The family do not believe their father would have agreed voluntarily to return to Russia.

"How could he sign something when he’d already said too much during his interview," asks Anastasia.

“He wanted to stay in Ukraine. They exchanged him, knowing what would become of him – how can that even happen? It’s totally incomprehensible.”

The family feel bitter about what they see as the lack of sympathy from some of the Ukrainian journalists who interviewed him, and in particular Ramina Eshakzai, who after his death called Nuzhin “a wonderful actor’ and said it was at least a “positive thing” that more than 20 Ukrainian soldiers had got their freedom in return for his.

"She interviewed him, smiled in his face, earned money from him,” says Anastasia. “And then she said: so what if he died."

Nuzhin’s family hopes that those responsible for Yevgeny's death "will be punished, no matter the cost”.

The family would also like to say goodbye to Yevgeny properly, Anastasia says: "We would like to retrieve the body. But we understand that whoever gives us the body will certainly have blood on their hands, will have been involved in his murder. That’s why I think it's impossible right now."

"We just want to understand what happened," she adds. "And since this is how things have turned out, we’d like to at least give a human being a decent burial. The things that happened are on the conscience of those responsible. Everything will come back on their own heads."

Makeshift morgues and pardons

In the months since Nuzhin’s death, fighters from the Wagner group have been playing a key role in the fighting in eastern Ukraine, and in particular in the gruelling Russian assault on the town of Bakhmut.

At the end of December the US National Security chief, John Kirby, said he believed more than 900 Wagner fighters had been killed.

Over the New Year holiday a video appeared on Russian Telegram channels showing Yevgeny Prigozhin visiting a makeshift morgue in Bakhmut where piles of dead bodies were clearly visible.

In January another video emerged showing Prigozhin congratulating the first group of prisoners to return home from the frontline after completing six months of service, and apparently being given their freedom. “Don’t drink, don’t do drugs, and don’t rape any women,” was his parting message to them all.

The BBC and other media outlets have identified at least two people with convictions for violent assault and murder among them. Neighbours of one of them described him as “a terrible person”.

When Bohdan Papadin’s interview with Yevgeny Nuzhin was posted on YouTube in September it was billed as a ‘shocking video’ exposing how Russia is using prisoners to fight in Ukraine.

In the intervening period the involvement of prisoners has become almost mainstream.

Despite questions from lawyers and human right activists there has been no official clarification of the legal basis on which serving prisoners are recruited to fight in Ukraine, or freed on their return.

Yevgeny Prigozhin said the first group of prisoner returnees were granted pardons by Vladimir Putin. The president does have the constitutional right to issue pardons. But no information has so far been released about whether that right is being exercised in this case.

Back in Ukraine, Bohdan Papadin says he watched the video of Nuzhin’s killing and was shocked to see the same expression of complete calm in his eyes, that he had been struck by during the September POW interview.

“I guess that’s what being in a Russian prison for 23 years does to you,” he says. “You no longer have any sense of fear left.”

Additional reporting by Ilya Barabanov, Olesya Gerasimenko, Anastasia Soroka and Svyatoslav Khomenko; editing by Jenny Norton.

Translated by Camilla Yermekbayeva.

Read this story in Russian here.