Ukraine war: What do we know about Gazprom’s private army

The Wagner group is not the only private military company fighting in Ukraine. Tensions are rising with rival mercenary groups apparently linked to energy giant Gazprom.

By Elizaveta Fohkt and Ilya Barabanov.

For several weeks media outlets and Russian pro-war bloggers have been reporting tensions between Wagner mercenaries and private military companies linked to Russia’s giant state gas producer Gazprom. Wagner boss Evgeny Prigozhin confirmed the existence of three groups called Stream, Torch, and Flame at the end of April. Since the start of the year, Gazprom has been building its own private military organisation. The BBC asks what we know about the PMCs linked to Gazprom, and their involvement in the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

On April 21st, “Call Sign Bruce,” the Telegram channel of Russia’s Federal News Agency employee Alexander Simonov broadcast an interview with Evgeny Prigozhin. The Wagner Group founder was complaining about the other private military companies involved in the invasion of Ukraine.

“People with money think it’s an amazing idea, establishing their own PMC,” a clearly riled Prigozhin said. “That’s how they started to multiply. Gazprom has Stream, [billionaire] Andrei Bokarev has Redoubt, – the animals are going in two by two.”

In the interview he discussed how mercenaries from other PMCs had been sent to cover the flanks near Bakhmut, where Wagner was advancing, only to abandon their positions due to poor training and supplies.

“They want to tell the Kremlin how f**** cool they are, they’ve made their own army. But they’ve got no aviation, no artillery, no EW [electronic warfare], no signal intelligence. There’s no ammunition, no drones, no medics. That’s half the problem. The main problem starts when they realise they’ve got no control over what they’ve created. To fight properly, you need tactical commanders.”

According to Prigozhin, Stream mercenaries are being paid huge salaries: “enough to knock your socks off.”

In one video clip filmed by Simonov, Prigozhin is berating a group of unidentified mercenaries for abandoning their positions in Bakhmut, where many Wagner fighters were killed. The mercenaries complain about poor communication, ammunition, and chaos in the chain of command.

Prigozhin’s outburst was the first public reference to military units created with the support of Gazprom. But when the interview aired, many observers pointed to the fact that back at the start of this year, Prime Minister, Mikhail Mishustin, had given Gazprom’s shell company Gazpromneft permission to set up a private security organisation. It was founded in Omsk under the name Gazpromneft Guard [Gazpromneft Okhrana], and headed by Stanislav Bauman, former acting head of the Ministry of Internal Affairs for Arkhangelsk region.

Another company called Staff Centre [Staff-Tsentr], also registered in Omsk, was listed as a co-founder. Staff Centre is owned by a StPetersburg-based security firm, which has been run by Sergei Tochilin since the beginning of the war. He is thought to be same Sergei Tochilin who previously held the position of assistant chief of the FSB for Omsk region.

The government said that the private security company was needed to “protect Gazprom’s facilities.” But Ukrainian intelligence had already categorised the company as a private army, created in Wagner’s image.

The link between Gazprom’s PMC and Stream has not been officially confirmed, but after Prigozhin’s interview, more evidence appeared on social media that the groups he referred to really do exist.

Mercenaries complain to Putin

On 23 April a video message from Stream mercenaries to Putin himself was broadcast on the Telegram channel “War Commander Evgeny Linin.” In the footage, masked men in camouflage claim that Stream allegedly was founded by “department security personnel” at Gazprom, and had been dispatching fighters to Bakhmut from early April onwards. They joined flank positions, replacing Wagner fighters.

In their message to Putin, the mercenaries complain about the supply shortage and the “irresponsible” command of Stream. The group allegedly had to retreat as early as 17 April, at which point they said their commanders had used “death threats” to block their exit into the safe zone.

The mercenaries also complained that they’d been promised contracts with the Ministry of Defence, but once in Ukraine they were managed by Redoubt PMC (also mentioned by Prigozhin.) The name Redoubt appears in a video interrogation of a Russian prisoner, which was circulating on social media in late April.

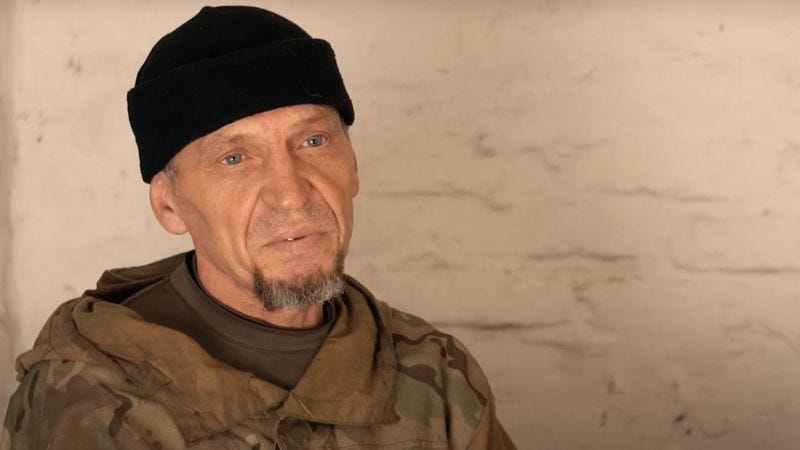

The footage shows a man with facial wounds thought to be Orenburg local, Alexander Tkachenko. The fighter says he was sent to the front with Stream under the command of Redoubt PMC. He says that Gazprom has two more PMCs: Torch, and Flame, controlled by the Ministry of Defence. According to Tkachenko, Gazprom established combat divisions right at the beginning of the war, using “security men from all over Russia.”

The soldier claimed that these mercenaries were trained at “Tregulai,” a camp in southern Tambov specialising in electronic warfare.

The BBC found Alexander Tkachenko’s social media pages. According to his profile on the Odnoklassniki site, he was born in 1996 and worked at “Gazprom Mining Orenburg”. His profile doesn’t say what his position in the company was, it does show that he was also a member of a closed group on Odnoklassniki called the “Orenburg Security Division”.

The group’s logo uses the symbol of the Volga Interregional Gazprom Security Department, which would fit the claims that Stream was formed from Gazprom’s internal security. Judging by Tkachenko’s social media activity, he likes weapons and is interested in all things military.

Tkachenko’s relatives did not respond to the BBC’s requests for comment.

PMC Redoubt which Prigozhin referred to, and the Stream mercenaries have in fact been operating for several years and previously were involved in providing security in Syria for the Stroitransgaz corporation, owned by billionaire businessman and Putin associate Gennady Timchenko.

Unlike Wagner, Redoubt didn’t participate in large scale attacks or offensives whilst in Syria, carrying out security activities instead. Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Stream was a minor organisation in comparison to Prigozhin’s group.

Several months ago the first reports appeared that Redoubt were actively recruiting, and sending fighters to the Ukraine front. There is a Redoubt Telegram channel which regularly posts pictures from the frontline, and recruitment announcements.

The Russian independent news outlet Vazhnie Istorii has been collecting data on fighters who went to Ukraine and committed crimes on their return to Russia. It found a court case in Valuysky region which mentioned Redoubt. Rostov citizen Kirill Topchev, sentenced for a drug offence, was recorded as a member of Redoubt who had been sent to Ukraine last spring.

Pro-war bloggers, including the Telegram channel Rybar, claim that Redoubt is linked to the Ministry of Defence. Gazprom doesn’t officially acknowledge the PMCs it supposedly runs, and nor does the Ministry of Defence. Even the pro-war bloggers – who tend to be franker about the course of the war than officials – only make guarded references to these groups.

Alexander Kots, a well-known military correspondent with the pro-war Komsomolskaya Pravda news outlet, broached the issue in an interview with the outlet’s radio channel.

“Gazprom apparently runs three PMCs: Flame, Stream and Torch,” he said. ”They recruit volunteers and transfer them to the Ministry of Defence. I don’t know whether this is true, and I can’t say what their future hold.”

“Setting up a PMC is not enough by itself. To be effective it has to be fully equipped, armed, and ideologically prepared, like Wagner. You can’t just throw in volunteers to plug the holes and call them a PMC, we already tried that with mobilisation.”

The dispute on social media between Prigozhin and the Gazprom-linked PMCs remains ongoing. In early May, the Wagner chief escalated matters further – he threatened to withdraw his fighters from Bakhmut, which has been besieged for six months, because of the crisis in the supply of mercenaries.

In multiple videos on Prigozhin’s channel, he complains that the flank units run by the Ministry of Defence and Gazprom are retreating. On 9 May a furious Prigozhin claimed that at least half of Torch fighters had refused to take up their positions.

“Why are you wasting state funds to recruit people and send them out as cannon fodder?“ said Prigozhin, in one recent diatribe apparently aimed at Gazprom bosses. “Their mums are going to come and make you pay for this. It’s time to stop this nonsense. This is a real war!”

The position Prigozhin claims that Torch fighters are refusing to take over is the bridgehead [fortified enclave] which Russia’s 72nd motorised rifle brigade have held since early May.

In one video, the Wagner chief claims that brigade fighters have actually retreated. This was confirmed by the Ukrainian command, and later by the spokesman for Russian Ministry of Defence, Igor Konashenkov, who announced on May 12th that the brigade had retreated several kilometres, leaving the Northern Bakhmut positions undefended and, as a result, opening the Bakhmut-Chasiv-Yar road to Ukrainian forces.

‘A true defender of the Motherland’

The scale of losses in the PMCs linked to Gazprom remains unknown. So far only one death has been officially acknowledged.

Erast Yakovenko, a 53-year old from Kabardino-Balkaria was killed in Bakhmut on 24 April.

Five days later an obituary posted on the site of the Prokhladny city education board under the headline “A Hero of Our Time”, said Yakovenko had died “performing his duties as part of the Stream detachment.”

This obituary and open sources suggest that Yakovenko, who was sent to the front in early April 2023, had a long association with the military. In the late 1980s he served [in a Soviet army detachment] in Poland as an artillery scout, before joining the transport police, later fighting in the Chechen wars in the 1990s, and leaving with the rank of lieutenant. After his retirement, Yakovenko was involved in the “patriotic education of the youth”. There are multiple photos of him online, teaching hand-to-hand combat to cadets. He also joined the Tersk Cossack army.

“Erast Yakovenko was a true defender of the motherland all his life!” Yakovenko’s obituary said.

The BBC contacted his relatives, who refused to comment.

In 2016, Yakovenko stood unsuccessfully for the LDPR party in elections in Orenburg. According to his candidate’s card, which was archived on the database of the electoral monitoring group Golos, at this time he was working as a senior security guard for Gazprom’s Southern Interregional Security Department.

Yakovenko’s story ties in with what both the mercenaries who have appeared on camera, and Tkachenko the captured Stream fighter have said previously. It appears that Gazprom is recruiting fighters from its own internal security divisions rather than going down the route used by both the Wagner group and the Defence Ministry of recruiting from the prison system.

A prisoner serving time in Bashkiria recently told the BBC that “hundreds’ of his fellow inmates had joined up to fight in Ukraine following two recruitment drives by Wagner, and another at the end of April by the Ministry of Defence. But, he said he had never heard talk of a PMC linked to Gazprom. Nor did the BBC find any reference to Gazprom on social media forums run by relatives of Russian prisoners who volunteered for service in Ukraine.

Ordinary Gazprom employees also seem unaware of any recruitment drives by PMCs. A BBC source in one of the gas giant’s many divisions in central Russia said there was no discussion of “corporate” PMCs, “even at a rumour-level.”

“Gazprom collects money for the army,” the source told the BBC, “And it’s unclear where that ends up. But unlike a lot of state-financed organisation, it’s not even advertising contract army service for volunteers [under the Ministry of Defence.]”

The BBC asked Gazprom’s press service for a comment, but received no reply.

Additional reporting by Ksenia Churmanova.

Translated by Pippa Crawford.

Read this story in Russian here.

LONG READ - Prison, war and revenge killing: the inside story of the Wagner ‘sledgehammer murder’ case

By Elizaveta Fokht and Anastasia Lotareva. In the summer of 2022 a Russian prison inmate serving a 28-year sentence for murder, volunteered to go to fight in Ukraine. He ended up dead, but not on the battlefield. The story of the life and …