How long can a Russian prisoner survive at the frontline in Ukraine? A BBC investigation

BBC Russian's analysis suggests those recruited to defence ministry units are dying increasingly quickly.

By Olga Ivshina.

“Good afternoon. My brother died on March 6th, 2023. He had been on the front line since November, after he left a prison colony. He phoned only once. We don't know anything about what happened to him since - not where he died, or how. No one has responded to any of my enquiries yet. It feels like there’s no one left alive.”

“Hello. My condolences to you. We’ve got the exact same story. It didn’t matter how much I searched for information about my son, there was nothing, like he just vanished. They didn't even tell me he had died. I myself had to write to the group where they provide information about casualties. The first time I wrote to them was in January, and they told me he was not listed among the dead, so I calmed down. And then it turned out that my boy had been killed back in December. They brought me some sort of empty coffin. But told me not to open it, just bury it, saying there wouldn’t be anything more in any case.”

You can see conversations like this every day in the chatrooms where relatives of prisoners who went to the war in Ukraine meet each other online. Hundreds of families are looking for information about those they love. From time to time, former prisoners who survived the front also show up in the chats:

“Only a few are coming back alive now. And they are usually ‘300s’ [the military shorthand for wounded men],” writes Vladimir from Karelia in one such chatroom. He had fought for six months before being pardoned. “Many die, some get taken prisoner. Assault operations are very tough. The chances of surviving them are about 25%.”

The casualty figures in this article are based on a list of confirmed dead Russian military personnel which the BBC has maintained since the start of the full-scale war together with the Mediazona publication and a group of volunteers. The database is compiled from open-source information.

To try to work out how long a prisoner can actually survive the war, we analysed the obituaries of prisoner-soldiers who have been killed in Ukraine – 9,327 of them. 7,417 had fought with the ‘Wagner’ private military company, and 1,910 were soldiers in ‘Storm’ combat units.

Representative of Wagner, including its late leader Yevgeny Prigozhin, recruited prison inmates from June 2022 to the end of January 2023. The deal was simple: two weeks of training, then five and a half months at the front in return for freedom, a clean criminal record and a monthly wage of around 100,000 roubles.

The Ministry of Defence took over prisoner recruitment from February 2023, and the contract conditions stayed the same until August. Then they changed significantly: the salary went up to 250,000 roubles, along with full military contractor benefits and a conditional release. The Duma changed the law to legalise the process, and regional governors even began posing with prisoners for snapshots. But there was a catch – instead of six months’ service, prisoners are now bound to fight until the war comes to an end.

But how long can a recruited prisoner expect to survive at the front? We selected a group of 1,040 men from the almost 9,000 dead for whom we have both a contract starting date and a date of death. The information comes from published obituaries and information from relatives.

Roughly half the group were Wagner members, the other half defence ministry ‘Storm’ unit fighters. Our analysis shows that deaths among Wagner fighters were evenly distributed while ‘Storm’ prisoners met their end more quickly after arriving at the front. Half of the Wagner men we identified had died within three months of signing a contract. For prisoners recruited by the MOD, half were killed in under eight weeks – a third less than their Wagner comrades.

Our figures do not prove that half of all convicts sent to the front died in the conflict. Our dataset is incomplete because we do not know the exact number of war dead and how many of them set off to fight from prison colonies.

The New York Times managed to get hold of a list of prisoners who were sent to Ukraine in October 2022 from Correctional Facility No. 6 in Chelyabinsk. Of the 196 individuals sent to war from that contingent, more than two-thirds survived. Many suffered serious injuries, however, including the loss of limbs.

But we spoke to two sources in Wagner who were involved in recruiting prisoners, and they said those despatched to war in subsequent batches were more likely to be killed. Their assessment is borne out by the data we have gathered from open sources.

From January to early March 2023, confirmed weekly losses of Wagner members never dropped below 300 men. The largest single-day losses suffered by Wagner occurred on March 24th-25th - 182 men were killed, of whom 141 were prisoners. These figures are merely what we can establish from open sources: the real numbers are likely far higher.

Wagner boss Yevgeny Prigozhin put the casualties among his men in the fighting for Bahmut at 22,000 dead. We have accurate information about the names of 10,348 of them, or slightly less than half. The NGO ‘Rus’ Sidyashaya’ - ‘Doing Time in Russia’ - believes Wagner sent almost 50,000 prison inmates to the front. Prigozhin himself, as well as Pentagon officials, mentioned similar numbers.

Meanwhile, human rights activists reckon the defence ministry may have despatched more than 60,000 convicts to the fighting by March this year. The survival rate among them is not known. But the prisoners themselves believe that between 50-70% of those serving in MOD units perish.

Why are prisoners killed so quickly?

One reason why defence ministry recruits die faster than Wagner-contracted prisoners might be a lack of preparation. All newly-contracted prisoners are supposed to be trained away from hostilities for a two-week period. Given that we did not find anyone who was killed in two weeks or less among the Wagner contingent, the procedure appears to have been observed. But we found more than a dozen convicts killed in that timespan from the ‘Storm’ units – in other words, at a time when they had been told they would be at a training ground. Relatives of prisoners confirm such cases:

“My husband just had signed his contract on April 8th and was in a stormtrooper unit by the 11th already. That is, at war,” says the wife of a ‘Storm-Z’ convict. “At the time, I was calm, because I was sure there would be the two weeks of training they talk about, and there’d be nothing to be scared of till the end of April. I waited for him to call me. And on April 21st, he died! And there had been none of it, no training at all.”

Men who have fought in ‘Storm’ units say defence ministry-recruited convicts are usually taken for training and combat unit allocation to the self-proclaimed Luhansk and Donetsk ‘people’s republics’ in occupied Ukraine. On arrival from prison camps, they often find they are refused the basic items for soldiering: shovels for digging trenches, first aid kits, and even serviceable rifles.

Watch Olga Ivshina’s report from 4’04”

“Many soldiers got guns that were unfit for battle, and completely broken – for example, with a mechanically damaged barrel, or lacking sights,” wrote the pro-war blogger Vladimir Grubnik, who was involved in supporting ‘Storm’ units. “When the commanding officer found out that Ivanov or Petrov’s rifle was unsuited to combat and needed replacement, he would say it was impossible: the weapon had already been assigned to someone, and the strict military bureaucracy can do nothing about it. What a soldier is supposed to do on the frontline without a first aid kit or shovel, and with a busted rifle, remains a mystery!”

Ukrainian intelligence officers wrote a report on Wagner tactics that noted “assault groups never retreat without orders... Unauthorised departure of the unit or a retreat without sustaining injuries is punishable by on-the-spot execution.” This also leads to additional personnel losses.

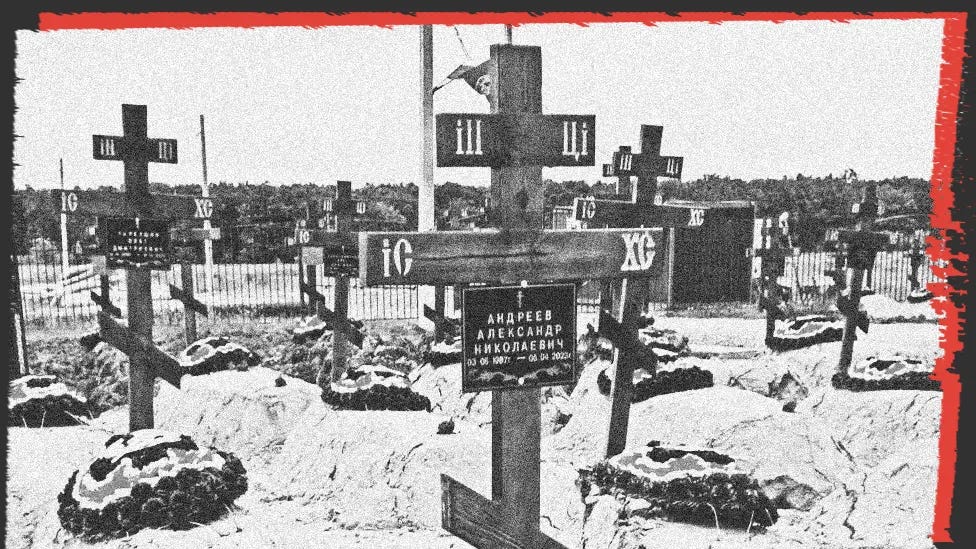

Insubordination or an apparent attempt at escape can also result in immediate execution by shooting, followed by burial in a cemetery in Luhansk region. The relatives of five dead Wagner members told the BBC that in such cases salaries were not paid and the bodies not returned. They had had to go to Luhansk at their own expense to retrieve their deceased loved ones.

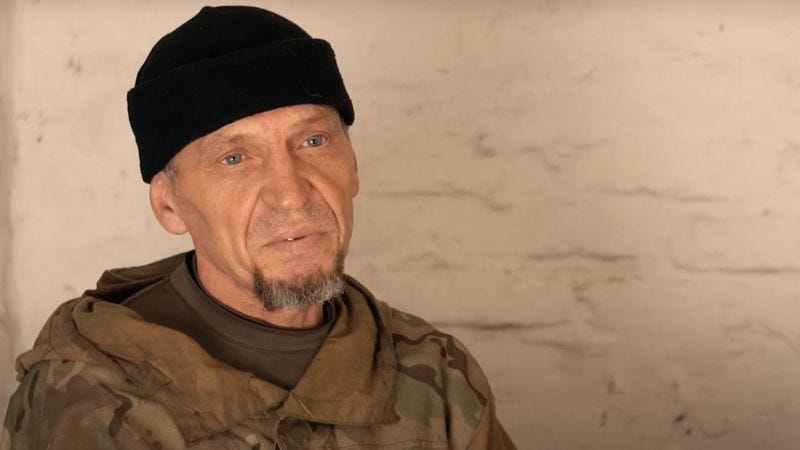

The most infamous case of punishment within Wagner was a video of a man being murdered with a sledgehammer. Yevgeny Nuzhin had surrendered to Ukrainian forces, saying he wanted to fight on their side, but was returned to the Russians in a prisoner exchange. The gruesome killing took place shortly afterwards.

LONG READ - Prison, war and revenge killing: the inside story of the Wagner ‘sledgehammer murder’ case

The story of the life and death of Yevgeny Nuzhin is a grim illustration of how Russia is increasingly using its prison population as a source of new blood on the deadly frontline in Ukraine.

How effective are combat prisoner units?

More and more, the Russian army is organising waves of attacks with small assault groups, just as the Wagner group did during the storming of Bahmut.

Prisoner units are used to attack fortified Ukrainian army positions, forcing the Ukrainians to open fire and reveal the locations of their artillery and gunners. The Russians then shell the positions or attack them with drones. The tactic is moderately effective, experts say, but leads to high personnel losses.

“One characteristic feature of this war is the huge number of drone strikes and artillery attacks,” notes Samuel Cranny-Evans of the Royal United Services Institute. “To survive in such conditions, it is necessary to constantly maintain high manoeuvrability of combat units, and good coordination with neighbouring ones. However, poorly trained soldiers - primarily prisoner units – are incapable of this."

Prisoners are thrown into the most difficult frontline spots, he explains, to maximise the preservation of elite units that suffered heavy losses during the early stages of the invasion in 2022.

For as long as the frontline remains unstable, prisoner unit operations will be relatively effective, however. Ukrainian soldiers say they are increasingly short of ammunition, and in such circumstances they will be less ready to expend it on small, scattered targets.

Compared to the first months of the war, Russia has significantly altered its operational tactics. Complex airborne assaults or sabotage operations have been abandoned in favour of ‘meat storms’.

“It eventually works to the advantage of the Russian army,” says Cranny-Evans. “They gain small territorial acquisitions, but at the expense of significant human losses.”

Every time a Ukrainian village is captured, the military commanders responsible get the glory. With manpower reserves made up of convicts, they can well afford the price of such incremental advances at the front.

BBC is blocked in Russia. We’ve attached the story in Russian as a pdf file for readers there.

Read this story in Russian here.

English version edited by Chris Booth.

50 thousand confirmed killed. What we can say about Russia's losses in Ukraine to date

By April this year, the true number of war dead may have reached almost 125,000.