Russian volunteer casualties outnumber deaths among convict soldiers

A new dynamic at the frontline – and what it tells us both about Russia’s losses, and the manpower available to continue the war on Ukraine.

By Olga Ivshina.

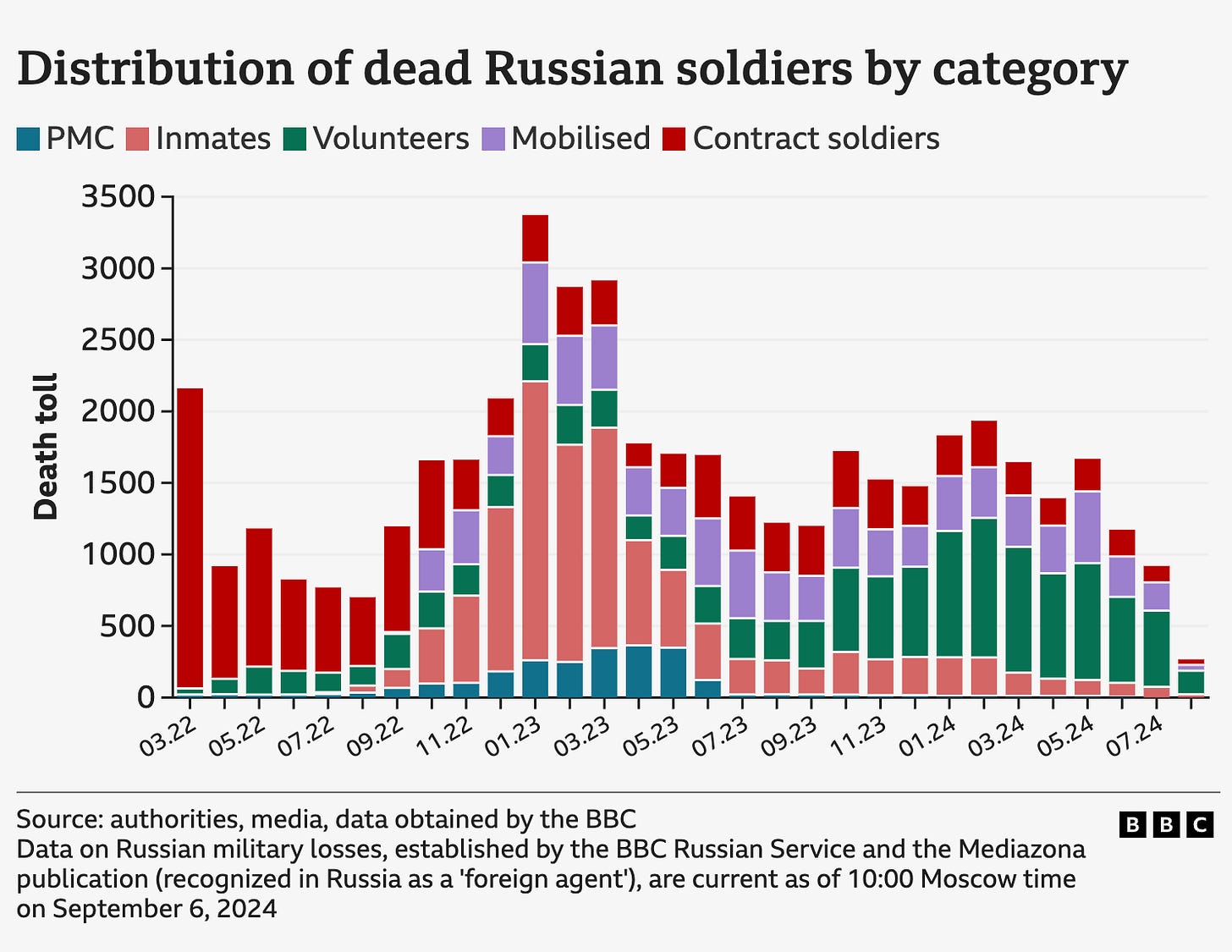

The majority of Russians killed at the front in recent months had nothing to do with the military when the full-scale invasion began. But if till now the largest cohort of casualties was composed of convicts recruited from Russia’s prisons, the dynamic has just shifted: volunteers who signed up after the start of the war in Ukraine now top the death toll.

According to the BBC’s calculations, overall losses on the Russian side may have reached almost 150,000 men. The number of seriously wounded who cannot return to the battlefield may amount to three times more – 450,000.

One in five – a volunteer soldier

Open data analysed by BBC Russian, in collaboration with‘Mediazona’ and a team of volunteers, has now identified the names of 68,011 Russian soldiers killed during the war inUkraine. Among them, we have been able to confirm the deaths of 13,152 volunteers – 20%, or one in five.

For the first time since the full-scale invasion, casualties among volunteers now exceed other categories, including prisoners (19% of all confirmed deaths) and mobilised soldiers (13%).

Obituaries and statements by relatives of the dead allow us to infer that most of those who signed contracts after the war began did so voluntarily. There are exceptions, especially among conscripts, when individuals say they were pressured into signing up: in Chechnya, some men joined to prevent mistreatment of their families, while some convicts and remand prisoners have also spoken of threats and coercion.

Training for men who have hitherto worked in the civilian sector can be as brief as ten days, and sometimes only three, before they are despatched to battle. Since October last year, weekly casualty figures of volunteers have not dipped below 100 men – and in some weeks, we have recorded more than 310 deaths.

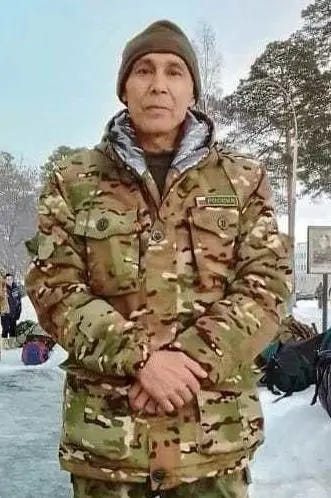

"After completing school, he did not continue his education and did not serve in the ranks of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation" — this line from the obituary of Rinat Khusniyarov is typical of many dead volunteer soldiers. Khusniyarov, from Ufa in the Russian republic of Bashkortostan, worked at two jobs to make ends meet - at a tram depot and a plywood factory. He was 63 years old when he signed his contract with the Russian army in November last year.

In a photo taken before he was sent to the front, Khusniyarov was pictured wearing modern camouflage trousers with knee pads and a jacket with a fleece-lined hood. Not all recruits are so well equipped. But Khusniyarov lasted less than three months of fighting: he was killed on February 27th.

Most of the volunteers dying at the front are aged between 42-50. They number 3,874 men in our list. The oldest volunteer killed was 71 years old, and a total of 209 contract soldiers above the age of 60 have died in the war.

Up to 150,000 war dead

Real losses are clearly much higher than we can establish through open sources. Military specialists suggest our analysis of Russian cemeteries, war memorials and obituaries captures 55-70% of the true death toll – suggesting that losses range from 97,158 to 123,656 men killed in action.

The numbers increase sharply if we include deaths in the so-called ‘people’s militias’ of the self-proclaimed Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics. Their data is either no longer published or was never published in the first place. However, obituaries and reports of searches for men missing in action lead us to conclude the Donbas units have lost 21,000-23,500 men.

That brings the total death count on the Russian side to between 118,158 and 147,156 troops killed in the war.

On top of that figure we must add those so badly injured that they cannot return to the fighting. The most conservative estimate, made by journalists at Meduza, was based on compensation payments doled out in 2022. They calculated that the wounded vs. killed ratio was at least 1.7-2.0 to 1. Most military experts believe the ratio is more like 4:1 – numbers confirmed by witness accounts from the front.

Including those missing in action, we believe the number of men no longer able to participate in the war comes to between 360,000-450,000.

A top-down recruitment plan

While exact figures are impossible to come by, we can extrapolate trends from the thousands of obituaries and statements we have analysed.

Rising casualties among volunteers is in part down to their deployment to the most difficult sectors of the frontline, notably in the Donetsk region, where they form the backbone of reinforcements for depleted units.

Russia’s ‘meat storm’ strategy – headlong assaults on heavily defended positions with no regard to the number of men killed – continues unabated. Sometimes, hundreds of men are killed on a single day. In recent weeks, the Russian military have made desperate (if unsuccessful) attempts to seize Chasov Yar and the town of Pokrovsk with such tactics. We have seen three times more obituaries and other reports during this period than the average for 2024 to date.

The Russian government is anxious to avoid a new, official mobilisation, and is therefore ramping up the call to volunteer for service – along with the incentives to do so.

Remarks by regional officials suggest they have been tasked from the top with a recruitment plan from the areas under their administration. To fulfil it, they advertise on job vacancy websites, contact men who have debt and bailiff problems, and conduct recruitment campaigns in higher education establishments.

Most of the men signing up come from small towns in parts of Russia where stable, well-paid work is rare. Some are barely literate and do not understand the contracts they are signing: they hope to serve a year and return home, even though all contracts are now essentially termless, and will last at least until the cessation of hostilities.

Trawling prisons and detention centres

As the supply of convicted prisoners drains away, thousands of men facing criminal prosecution are now joining the army, taking advantage of legislation introduced last year. Investigating officers are keen to ensure suspects are aware of the provision, which ensures the case will be closed permanently if the contract is completed, a state medal is awarded, or the soldier is discharged for health reasons.

"Currently, the only ones not being accepted into the war are those accused of terrorism, treason, sabotage, especially serious crimes, or certain sexual offenses,” one investigating officer told the BBC previously. “Everyone else is being sent off to the special military operation very quickly."

According to an order from the Ministry of Defence, the Ministry of Justice, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs, detention centres are now required to send regular lists of inmates to military recruitment offices.

"The military takes almost everyone, except for those who are clearly unfit for health reasons,” the investigator said. “For example, they’ll sometimes take drug addicts, so long as they are not officially registered as such. And many aren't, because their families had been treating them in private clinics."

Such cases are classified in our database as volunteers, since they have not been convicted of a crime.

A small number of the volunteers killed were foreigners: we have identified the names of 265 such men, many of whom were from Central Asia - Uzbekistan 47, Tajikistan 51, and Kyrgyzstan 26.

Last year saw reports of recruitment for the war in Cuba, Iraq, Somalia, and Zambia. The governments of India and Nepal have formally called on Moscow to stop sending their citizens to Ukraine and repatriated the bodies of the fallen. Nepal asked for all of its mercenaries to be returned from the front. So far, the calls have not been acted upon.

The Russian authorities often use a foreigner’s official immigration status as leverage: those who agree to ‘work for the state’ are promised they will not be deported, and will enjoy a simplified route to citizenship - assuming they survive. Many such men cannot read the paperwork they are expected to sign.

Cash bonuses – but poor quality kit and minimal ‘training’

Salaries that are 5-7 times higher than the regional average, plus social benefits, are a serious incentive to sign up for service. A study by Novaya Gazeta Europe found that the recruitment bonus has increased 80 times since the start of the war.

Our research shows that 12 Russian regions significantly increased such payments over the summer. Krasnodar raised the bonus three times this year, and Chelyabinsk twice – both are among the leaders in absolute losses.

A soldier who signed a contract with the Russian army in November last year told the BBC he was promised two weeks of training at a shooting range before deployment to the front. There he would enjoy three months of coordination in the rear.

"In reality, people were just thrown out onto the parade ground, and dished out some gear, half of which was made in China. There were three days of drills we didn’t understand, two shooting sessions at the range — and that was it,” he said. “We were loaded onto trains and sent to the front. About half of us were thrown into battle straight out of the carriages. As a result, some people went from recruitment office to the frontline in just a week."

Soldiers say new recruits are taught how to hold a weapon and conduct an assault, and nothing more.

"There is an element of knowledge, sort of understanding what's going on around you, understanding when you can and cannot stand up fully, for example, where you should and should not go to the toilet. They might sound like relatively straightforward things, but there are basic skills that are supposed to be taught to soldiers so that they understand these things and they don't needlessly expose themselves. So if the recruits aren't receiving that kind of training then they might make quite simple mistakes for a military that lead to them being targeted,” notes Samuel Cranny-Evans, an analyst at the Royal United Services Institute in the UK.

“They probably do not receive the level of training that is required to get those kind of survival skills. For example, basic understanding of things like camouflage and concealment or how to move quietly at night, how to move without creating a profile for yourself during the day. Those things are generally taught as basic infantry skills."

By comparison, soldiers sent by the USSR to Afghanistan were trained for four to six months.

While the government is willing to raise salaries for recruits, supplying proper equipment remains a genuine problem:

"What are they issuing now? Well, it varies, but most often it's some random set of uniforms, standard boots that wear out within a day, and a kit bag with a label showing it was made in the mid-20th century,” one solder says. “A random bulletproof vest and a cheap Chinese helmet. It's impossible to fight in this. If you want to survive, you have to buy your own equipment."

Survival on the battlefield is lower still because few recruits have a grasp of first aid, and those assigned a medical kit do not know how to use it. An official study by the Main Military Medical Directorate of the Russian Ministry of Defence says that 39% of their soldiers die from limb injuries – and that mortality rates would be significantly improved if first aid and subsequent medical care were better.

Our method of calculation

New names of the dead and photographs from funerals are published every day throughout Russia. The identities are disclosed by the heads of Russia’s regions, representatives of district administrations, local media, educational institutions where the deceased had studied, or by relatives.

BBC Russian, Mediazona, and a team of volunteers examine this information and add it to the database we have been compiling since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. We consider death confirmed if its announced by an official Russian source or the Russian media, or if it is made public by relatives. Other sources are also counted if they are accompanied by photos of the funeral.

Generally we do not include losses by the DNR and LNR “republics”, though if a Russian citizen has volunteered to go to war for such units, we do count him.

The kind of military unit concerned is determined either by reports of where the deceased served or by the insignia on his uniform. While conscripts, volunteers and convicts are not separate types of troops, we categorise them independently in order to compare losses against those borne by professional fighting units of the regular army.

The category “Other troops” in our graphics covers air defence servicemen, Nuclear Biological and Chemical troops, communications specialists, air force ground troops, Interior Ministry servicemen, transport troops and the military police.

Read this story in Russian here.

English version edited by Chris Booth.

Everyone’s at the front line. Penal colonies in Russia are closing down: there’s nobody left to ‘do the time’

The war in Ukraine has seen tens of thousands of Russian prisoners recruited to the battlefields.

Раньше - лет 20 назад - ведущие мировые информационные агентства не опускались до уровня желтой прессы.

С ее безапеляционным враньем, передергиванием фактов, разгоном отрицательных эмоций до истерии. Поздравляю, BBC - вы полностью дисквалифицировали себя, как профессиональные журналисты. Не пресса- помойка! Одни названия статей чего стоят: "Жена оккупанта" - вы это пишете для задуривания граждан Украины?

Так они и так из-за переформатирования мозгов набрекрень - давно с историей и логикой и не дружат. В России, понятное дело, на таких эпитетах получишь только обратное фак. Вы о себе и своей стране побольше пишите. О том, как хорошо развивается в Америке промышленность, выпускающая оружие.

И ваше оружейное лобби отлично убивает не только жителей Украины, но и своих сограждан.