Everyone’s at the front line. Penal colonies in Russia are closing down: there’s nobody left to ‘do the time’

The war in Ukraine has seen tens of thousands of Russian prisoners recruited to the battlefields.

By Olga Prosvirova, Olga Ivshina.

A sharp decline in prisoner numbers has brought about the closure of a number of Russian jails. It has nothing to do with humanitarian reforms, however, and everything to do with the war in Ukraine, now in its third year.

Convicts have been heading off for the front lines since summer 2022, initially recruited by the Wagner private military company. The process is now handled under the auspices of the Ministry of Defence. The prisoners who aren’t recruited, and are left behind, are then transferred to other jails – and often to worse conditions.

‘Tanbridge’ 091

"One of our fellow countrymen was killed during the Special Military Operation on the territory of Ukraine.” The social media post, published in the ‘I’m from Ulan Ude’ VKontakte group, is typical of its kind: the dead man is described as a ‘hardworking, conscientious and responsible’ tractor driver.

His record was unblemished and he had done his obligatory military service before signing up to Wagner. But Rustam Valiulin, from the village of Enkhor in Buryatia, wouldn’t come home alive.

The post closes by saying he left behind a brother and a son. The authors might have added that the one person he didn’t leave behind was his mother. Because he had killed her.

Just before New Year’s Eve eight years ago, Valiulin had quarrelled with his mother, accusing her of drinking too much and too often, and recalled his father’s death – she had ‘killed him with a knife’, according to a claim that was not contested during Valiulin’s trial.

He hit his mother in a rage, several times and with considerable force. She reached for a knife on the table. He noticed her move, seized it first, and stabbed her in the side. She tried to get away, but Valiulin caught up with her and kept on stabbing. The killer blow was to her chest. It punctured a lung and caused internal bleeding. Valiulin dragged her to the kitchen, leaving her face-down on the floor, before climbing up to the hayloft to sleep that night.

In the morning, he scrubbed up some of the blood and went to a shop for a bottle of vodka, which he drank.

Shortly afterwards, his brother found his mother’s body in the kitchen. The court records tell the whole story, and Valiulin was sentenced to almost 10 years in a high-security prison colony, IK-17 in Krasnoyarsk, roughly 1,500 kilometres from home.

Wagner picked up more than 140 men from IK-17. The BBC and Mediazona knows the recruitment figures for all of Russia’s jails thanks to a document listing compensation payments for the dead which we have seen and analysed. We have call signs, dog tags and death dates. [See this article for details.]

As still-living convicts, the men were promised a presidential pardon and a hero’s release if they survived a six-month contract. Rustam Valiulin had three years left of his sentence for matricide and the Wagner offer was compelling. He was assigned the nickname ‘Tanbridge’, and the dog tag number K252-091. The ‘K’ is presumably for ‘colony’ – kolonia in Russian – while 252 is the Wagner code for the prison in question, and 091 is the order in which he was recruited from the total who joined up from IK-17. Valiulin was killed on March 4th, 2023.

Changes afoot in the "Torture Region"

Krasnoyarsk region is known to be among the harshest, perhaps the cruellest, of the regions where Russia’s penitentiary system flourishes. Videos of torture and prisoner abuse at IK-17 have surfaced. 46 of the inmates who signed contracts with Wagner were killed in the war.

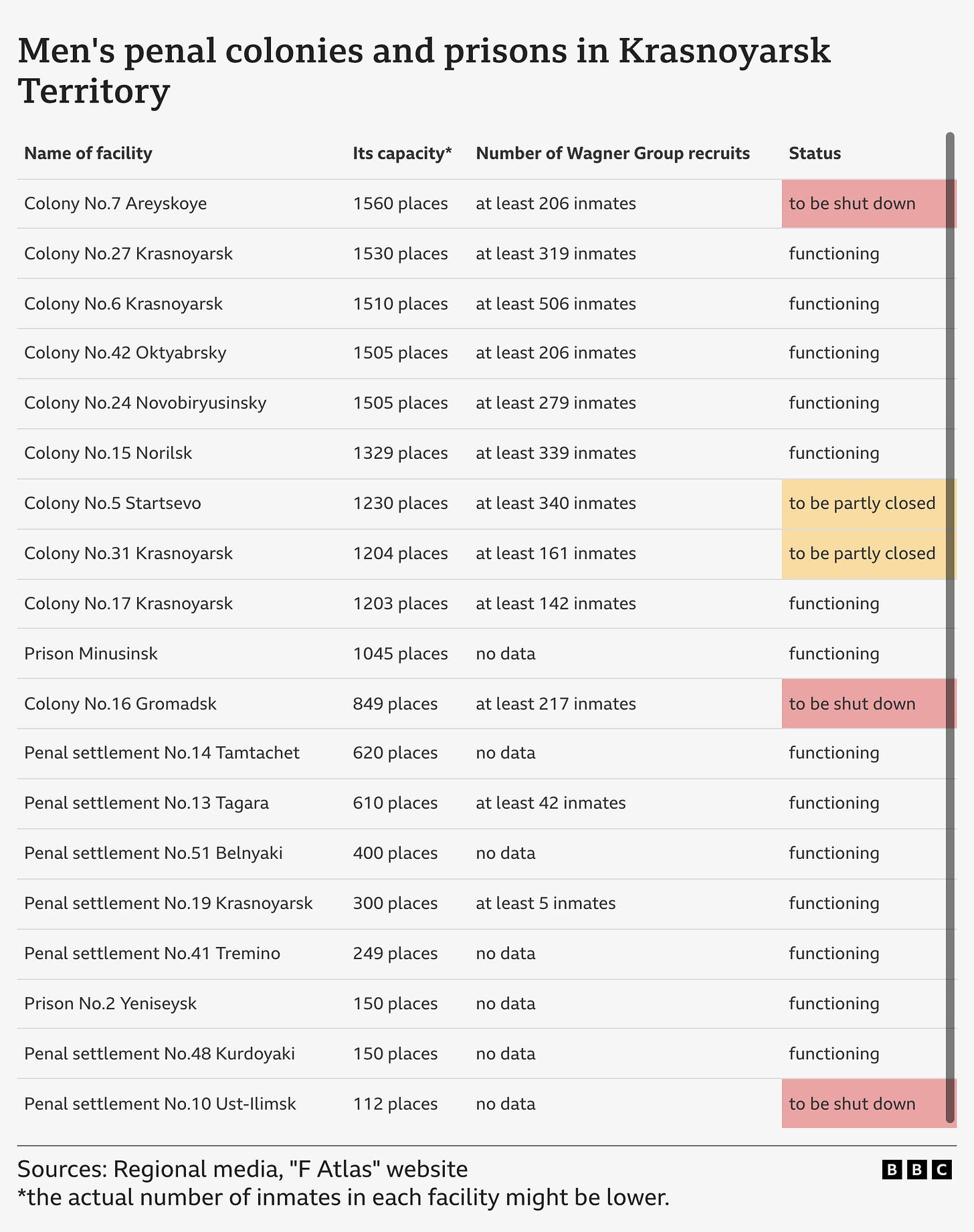

Last September, there were rumours the Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN) was planning to close another Krasnoyarsk jail, IK-7, in the village of Areyskoe, for ‘lack of prison population’. The rumours were confirmed by the regional human rights ombudsman, Mark Denisov, who linked the decline in convict numbers to the war effort. As of January 2024, he noted, the region’s FSIN institutions had seen a 17.5% drop in numbers of inmates – from 15,182 in 2023 to 12,530.

The law allowing prisoner recruitment was passed in June 2023, and its provisions were expanded this March to lift a ban on those guilty or accused of particularly serious crimes. Wagner took on more than 2,800 men from Krasnoyarsk institutions alone.

As well as IK-7, the regular regime prison IK-16 in the village of Gromadsk was also closed. The combined capacity was 2,409 men. Plans are in place to shut down IK-10, parts of IK-31 and IK-5, and the hospital at IK-5.

We spoke to a former IK-7 inmate, who wished to remain anonymous, about visits from Wagner and the defence ministry recruitment teams.

“It was a simple matter: every man made up his own mind and weighted up the risk. Some went and fought, and some survived, and some didn’t come back. I asked one guy if he was sure he knew what he was doing. He had served half of his 10-year sentence. He said he was: ‘Well, it’s 50-50. I will either survive or I won’t.’ I recently heard he died near Bakhmut.”

The head of IK-16, Pyotr Antsiferov, told a news outlet that the prisoners left over were being transferred to other colonies and the staff offered jobs elsewhere, too. There were more than a hundred, only a quarter of whom were from Gromadsk. Antsiferov said he himself didn’t know what job he might end up with.

The last of the IK-7 prisoners were sent over the spring to the notoriously abusive IK-17 where Valiulin had served. Head and shoulders above other local prisons for recruits, however, was IK-6, situated in the regional capital city, Krasnoyarsk itself. The maximum security jail was designed for 1,410 inmates, with another 100 beds for pre-trial detention. More than 500 left for the front line – the personnel number of the last dead man on our list is 506. We know that 136 men died there.

It's not about humanitarian reform

Russia’s prison population has been in decline in recent years. Olga Romanova, the founder of the ‘Rus’ Sidyashaya’ – ‘Doing Time in Russia’ – charity, says this is in part due to the decriminalisation of some articles of law, such as those on domestic violence.

The authorities also began to develop different formats for detention and punishment. Even before the war in Ukraine, the plan was to lose 10% - 88 – of FSIN’s 900 institutions. A 2021 policy document said the target was for a colony population of 400,000 by 2024 and between 250-300,000 by the end of the decade.

On the eve of the invasion, the official figures were 465,000 prisoners across Russia. By autumn 2022, FSIN had stopped publishing a detailed breakdown of prison data – the same time as convicts started to be recruited.

On January 1st 2023, an update was at last published: 433,006 inmates across the FSIN system. But then in October, less than 10 months later, the deputy minister of justice put the total far lower, at an astonishing 266,000. There was some discussion about whether the bureaucrat, Vsevolod Vukolov, had been misquoted, but a video recording of the meeting shows this is not the case. The discrepancy has yet to be clarified officially.

"FSIN classified the number of prisoners in 2022 in such a way that no one could work out how many were recruited," says Olga Romanova of ‘Doing Time in Russia’. What’s more, she says, recruitment is no longer happening in big bursts of activity as under Wagner, but more like a steady drip feed that draws less attention, but which in effect picks up a greater number of recruits. Some such men, she adds, have been through the system more than once, and are therefore even harder to keep count of.

“Plus, from the start of the prisoner recruitment campaign, they were taking them from remand centres, where they had yet to be convicted. It used to be illegal, but since September 2023, it isn’t. And it’s hard for me to keep track of them if they haven’t been convicted of anything.”

Romanova estimates that around 200,000 convicts may have been sent to the front. The figure fits well with the one mentioned by Vukolov, the deputy justice minister. It would mean that the closing down of prison colonies is not a function of more humane criminal justice practices in Russia, but of the despatch to war of the men who had filled them.

More than half of them are empty

A number of Russian prison colonies have already been confirmed closed. Among them, IK-44 in Belovo, in Siberia’s Kemerovo region. It was designed to hold 1,210 men.

Vladislav Kanyus was one of them. He was convicted of the murder of 23-year-old student Vera Pekhteleva. It took him three hours to kill her.

In court, he protested his innocence and refused to cooperate with the investigation, but was found guilty and sentenced to 17 years. He didn’t stay long in Belovo, though, but joined up with Wagner, survived the fighting, and was pardoned by President Putin. As Kremlin press secretary Dmitry Peskov said, guilt can be “redeemed with blood in assault brigades, if shot at, or under shellfire.”

In Sverdlovsk region last year, four correctional colonies were closed, allegedly because they were ‘no longer cost-effective’. Another two will shut up shop later this year. Wagner alone took at least 1,388 prisoners from this part of Russia.

In Nizhny Novgorod region, the FSIN authorities refused to confirm if a prison closure there was connected to prisoners leaving for the front. A facility for first-time offenders in Komi Republic is also being closed up: as part of measures to ‘reduce crime’, they say.

Last summer, the finance ministry in Moscow proposed shutting down 57 colonies because of ‘unnecessary expenditure’. In some prisons designed for 1,500 men, there might be as few as 300 prisoners, for example. The idea was to build hybrid prisons that also served as remand centres, thereby reducing transportation costs. Yet the budget for building only the first three such facilities has already been set at 53 billion roubles, as the justice minister reported to Vladimir Putin.

Transportation costs between colonies won’t disappear either: the criminal code allows the removal of a prisoner to a different location if there is no suitable jail locally, or if space has run out in it, or if the man faces a threat to his safety. In practice, according to a Moscow lawyer who wished to remain anonymous, prisoner well-being has nothing to do with it: the system operates according to bureaucratic logic and a prisoner transfer often ends up taking the inmate to an even worse place.

"In pre-trial detention centres, for example, there’s a ritualised 'torture' procedure for new inmates,” he said to the BBC. “They are constantly moved from cell to cell, kept from being allowed to 'nest,' or get used to one place. They are kept in a state of discomfort... And it’s not a matter of law but pure psychology. In some cases, a transfer may turn out for the better, but it’s pure luck.”

Hybrid colonies will in theory mean more courtrooms, prosecutor offices, observer rooms and lawyers based in prisons. Judicial hearings in the colony grounds, as in the case of Alexei Navalny, will be more common. But that will mean it will be harder for relatives, human rights activists and journalists to get access to the jails and remand centres once they have been removed from city centres.

"The consequences of war"

The biggest factor in the reduction of convict numbers is the war, says a lawyer from the Siberian Federal District: “Everything else comes second.”

Yulia Tay, another lawyer, agrees. "The FSIN, like any government agency, will never reduce the size of its 'flock' or the extent of its powers. So the reason for the reduction in the number of prisoners is definitely not inspired by the FSIN itself."

Accurate information about exactly how many convicts have gone to the front is not available. Wagner recruited around 50,000 men, but then the Ministry of Defence took over the process, and prisoners no longer have to fight for half a year, but to the end of the war, whenever it may come.

Private military companies like Wagner disclose data on recruits and casualties, but the defence ministry does not. Our work with Mediazona showed that as well as Krasnoyarsk region, the top suppliers of convicts to the war were Irkutsk, Volgograd, Transbaikal and Orenburg regions.

None has reported prison ‘reductions’ yet, but there are rumours in Volgograd that IK-5 will be closed soon. It is a high security facility for almost 1000 inmates. And in Orenburg, discussions have begun to merge two high security prisons, one for first time offenders and another for those returning to a life behind bars.

The war is also supplying fresh prisoners into jails and investigative isolator units. The Verstka news site estimates that in the past 12 months, more than 107 people have been killed at the hand of a soldier returning from the front line. A similar number have been seriously wounded. The figures were based on court databases in the public domain.

Artyom Samedov was jailed in 2020 for robbery, assault and bodily harm – he beat up four women during an attempted theft. He had previously been convicted of violent crimes and grievous bodily harm. The sentence this last time was seven years, but he joined Wagner and was pardoned by Putin.

When he got back home, drunk, he started flirting with an 18-year-old girl. When she resisted his advances, he stabbed her repeatedly with a knife. She survived, because passers-by heard her cries for help, and the ‘hero of the special military operation’ fled the scene.

In court, he tried to explain his action as the “consequences of war”. The court took this into account, as well as his service awards, and handed him a reduced sentence of six years this time round.

It is no longer necessary for a trial to be completed if you are ready to go to war: law enforcement officers encourage criminal suspects to volunteer for the front if they want their cases suspended.

Mark Denisov, the human rights ombudsman in Krasnoyarsk, called into question this new practice:

“The Special Military Operation will end at some point, and everything will go back to square one because the structure of society has not changed. In five years from now, we will have limits on violating the rights of convicts. Therefore, painfully, and at triple the cost, we will again begin building new prison facilities in our region.”

BBC is blocked in Russia. We’ve attached the story in Russian as a pdf file for readers there.

Read this story in Russian here.

Translated and edited by Chris Booth.

‘Immoral but effective.’ How the ‘Wagner’ private military company lost 17,000 prisoners in the assault on Bakhmut

BBC Russian continues its investigation into the Kremlin’s war dead in Ukraine.

Surviving Storm V – the brutal reality of life on the frontline as a Russian convict fighter

A disturbing firsthand account of how a convicted drug dealer from Moscow went from prisoner to frontline soldier and now asylum seeker in France.

I wonder how bad you have to have been in previous lives to collect the karma that results in being born in Russia?

(/snark)