"Desertion is a political act." Should Russians escaping the army be seen as victims of the war in Ukraine?

BBC Russian spoke to one of the Russian soldiers who deserted from the war in Ukraine and just arrived in France, where he is claiming asylum.

By Amalia Zatari.

By the start of this month, six Russian deserters who had fled the war, and initially sought refuge in Kazakhstan, finally made it to France. It was the first case of a group of ex-soldiers receiving entry papers to Europe.

But not all men who desert the Russian army were opposed to the war when it started. And finding out what they did at the frontlines is hard to verify. Should they be left to their fate?

Or are they a ‘forgotten category’ of asylum seeker? Should they be seen as political activists of some sort? Do such men – many thousands of them – deserve our sympathy, and better treatment?

BBC Russian spoke to one of the deserters who has just arrived in France – as well as with the human rights activists who are struggling to make the voices of men like him heard.

At the age of 18, Anton (we have changed his name at his request) desperately wanted to get away from home - but never really wanted to join the military. His great-grandfather had been a soldier, however, and his family encouraged him to follow in his forebear’s footsteps. Anton enrolled in a military academy.

But as the classes wore on, he began to lose faith in the Russian army. “I realised things weren’t how they seemed on TV,” he says.

Anton began to sympathise with the opposition, and wanted to quit the academy. But he was pressurised to stick with it, and graduated with the rank of lieutenant.

He was 23 when Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine was launched. Even before it started he’d officially objected to joining military exercises scheduled for annexed Crimea in early February. The choice was legally not Anton’s to make: the decision depended on his commanding officer.

“He drew a penis on my paperwork and said ‘You’re going. No other option.’”

Half way through the exercises, Anton recalls, “some generals began to show up at the training ground – conducting drill inspections, checking troops’ uniforms, yelling at the commanding officers. That was the first alarm bell that worried all of us.”

Like everyone else, he had been following the news. But he didn’t think a real war would start. “We all talked about the exercises, but we assumed it was just for show.”

At night on the 24th, the soldiers were formed into columns, given grid coordinates, and ordered forward. And at some point the road signs turned into Ukrainian ones. This was how Anton, as a member of the Russian army, found himself over the board and on the territory of Ukraine.

Back in Russia, there was a theoretical chance to resign from the army. But in Ukraine it was practically impossible, Anton says. “If you went to an officer asking to be discharged, they’d just ask ‘Are you a moron?’ I tried more than once to get back to Russia by faking illness, but it was hopeless.”

Anton was to spend almost six months in Ukraine. He says his job was working on communications for the military based in Zaporizhzhia. “My job was going up cell phone towers, and setting up satellite links.”

He was sent on leave in late August. On the day he got back, Anton decided to leave the country. Within 24 hours, he was in Kazakhstan. He got phone calls from his military unit – they wanted to despatch him to Ukraine again. “To begin with, I answered the calls and said ‘Sorry, I’ve been off drinking,’” he says, hoping to buy time so his commanders would not think he was absent without leave.

In Kazakhstan, he busied himself getting hold of certificates showing he had no criminal record from the Russian state information portal. He knew he needed them before he was put on a ‘wanted’ list. In November, he found out that a criminal case had been opened against him – Article 337, unauthorised leave from his military unit, with a maximum punishment of ten years in jail. Soon afterwards, he was declared a wanted man.

“Being sent to Ukraine doesn’t mean you don’t deserve help...”

Russians don’t need a passport to enter Kazakhstan – just an ID. After the war began, the country became a magnet for Russians escaping the country. At first, it was the political opposition and those opposed to the war in principle. But when Putin announced mobilisation, those at risk of being ordered to the front (conscripts or professionals like Anton) started to head to the country.

In the capital, Astana, Anton met Artur Alkhastov, a local human rights advocate and lawyer from the Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights. He had begun to support those leaving Russia, and help ensure they were not extradited back. At the same time, Alkhastov was making sure the stories they told him checked out. He wanted to weed out infiltrators from the Russian security services, and to identify which deserters may have been involved in war crimes.

“Not enough people understand that desertion at a time of war from the army of the aggressor state – that’s a political act. And it is followed by political persecution”

“I don’t think that just because someone was in Ukraine, they shouldn’t receive help.” Alkhastov says Russian deserters are also victims of war.

"The guys who were in the exercises back then [before the war]—I don’t see how they can be blamed. They were transported to manoeuvres, which are a routine part of military service,” he says. “Nobody from the military command asked them, ‘Do you agree to enter Ukrainian territory now?' Of course that wasn’t going to happen.”

A former Russian soldier, Alexei Alshansky, has been helping Alkhastov verify deserter stories. Now 28 years old, Alshansky quit the army in July 2022 with the rank of sergeant-major. He had served more than five and a half years.

When the war began, he was stationed near Moscow in charge of a training ground – meaning he was unlikely to be called to the front any time soon.

"I had subordinates, contract soldiers, sergeants, plus some people who came with the division to the training ground. We would just gather in my office, sit silently on the couch, staring at the wall like idiots, smoking a lot of cigarettes," Alshansky recalls about the early days of the conflict.

He started offering help as a consultant to an independent analytical group based abroad, Conflict Intelligence Team, that uses open source information to assess Russian military activities in Ukraine. His familiarity with army structures and operations meant his value was quickly evident. He resigned his army position and soon became a full member of the team.

When mobilisation was announced, Alshansky immediately bought tickets and left for Kazakhstan, knowing that as a recently discharged former contract soldier he would likely be among the first to receive draft papers.

In Kazakhstan, he came across Alkhastov and began to work with him: just like the opposition figures who fled the country, he believes Russian deserters should be thought of as political activists.

“Not enough people understand that desertion at a time of war from the army of the aggressor state – that’s a political act. And it is followed by political persecution,” he says.

Alexei Alskhansky met Anton in person in Kazakhstan to verify Anton’s account of his time in the army. Quitting his military job before mobilisation began meant Alshansky had been able to get a new passport in Kazakhstan and was free to travel to Europe. Anton’s situation was different: he had no passport (it had expired), he couldn’t get a new one (because of the criminal case against him) and he risked arrest and extradition to Russia (because of the international warrant).

“We cannot prove someone is an FSB agent. But we can sense if he’s suspicious”

Successfully passing verification himself, Anton joined Alkhastov and Alshansky, in checking out the backgrounds of other deserters. As well as with those who fled to Kazakhstan, they also work with men who ended up in Armenia, which can also be entered with an internal Russian ID, and countries like Serbia, Georgia, and Montenegro. Entering these three requires a foreign passport, but some who escaped mobilisation managed to keep hold of theirs.

“We cannot prove that someone is an FSB agent, but we can sense when someone seems suspicious - and then we tell human rights defenders to be extremely careful with them. You get some like that,” says Alshansky.

“To start with, we go through the documents the person has. Then we interview them and find out their story, asking questions and checking it as we go. I know some military bases myself, so if someone is from that area, I might ask, ‘Where’s the dining hall located?’ or ‘When you go in, you know that memorial there?’ And they go ‘yeah, yeah’, but I know there’s no memorial at all... it’s details like that,” Alshansky says.

Anton recounts meeting Alshansky in person several times. “Probably it was a month that I was going through all the details with him. We talked for a long time. And he ran me through his databases.”

“Let’s say a reputable organisation starts helping a deserter obtain a visa, and it later turns out that he was involved in the massacre in Bucha - it would be the end for both the organisation and this entire process”

“There was one guy who volunteered to fight, signed up, got to a training base, and only there realised what he had got himself into – because he saw there on Russian soil, at the training ground, the pits dug in the earth where they put those who refused to fight,” Alshansky shares. “He got in touch with us, having deleted his social media accounts. He didn’t realise we could see archived copies. They were full of slogans like ‘For Truth!’ and ‘Strength in Truth’ [in Russian the slogans play on the Z and V letters that came to symbolise war propaganda]. It showed he was into that shit. But when he saw what it meant in reality, he got scared and ran for it.

“But we don’t care about his views because at a minimum, he didn’t act on them – he never made it to the front. Do we know for a fact he wasn’t there? Yes. Do we know what kind of guy he is? Yes – not the nicest kind. But he deserted, and that’s a concrete refusal to take part in the war. And that doesn’t need further justification.”

It is harder to verify is someone has been involved in war crimes. “We look at the unit they served with,” Alshansky says. “If I know the unit wasn’t a part of the invasion at the time, and he says he didn’t participate in the war but deserted, then it speaks in his favour. But if we get a guy from some parachute regiment that we know was identified as taking part in the atrocities near Kyiv, for example, then you have grounds for suspicion.”

Verifying the accounts of those who were at the front for a brief period, and fled as soon as they could, is easier than with those who returned to the fight several times – perhaps after leave or hospitalisation, and possibly at different locations. Alshansky adds that what they did in their unit matters: “If they were a communications specialist, that’s one story. But if they were an assault trooper, that’s completely different.'

“Even If there are stains in a person’s history, they still need help and support if they refused to participate in the war and are being persecuted for it. For us, it's just important to understand what we can do with them next - refer them to human rights activists to help obtain European visas, or put them in touch with local human rights lawyers [in Kazakhstan or Armenia].”

Anyone suspected of committing war crimes has no chance of getting an entry visa. That probably includes all former assault troops, Alshansky says, given the nature of their job.

"It’s something we have to talk to human rights groups about. Let’s say a reputable organisation starts helping a deserter obtain a visa, and it later turns out that he was involved in the massacre in Bucha - it would be the end for both the organisation and this entire process. No European country would want to engage with this problem anymore," he concludes.

InTransit is a group based in Germany that helps anti-war Russians get out of the country and obtain European visas. Their coordinator (who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons) says it is impossible to be 100% certain that a soldier who fought in Ukraine did not commit war crimes there.

"But this is the point of the verification process: it is a tool that greatly aids in further work on obtaining visas and applying for asylum. The fact that these people have already undergone systematic verification by specialists allows the foreign ministry [of a European country] to trust them more. The bureaucrats who make the decisions see that their story has already been verified, so they have fewer doubts about the person."

A forgotten category of people

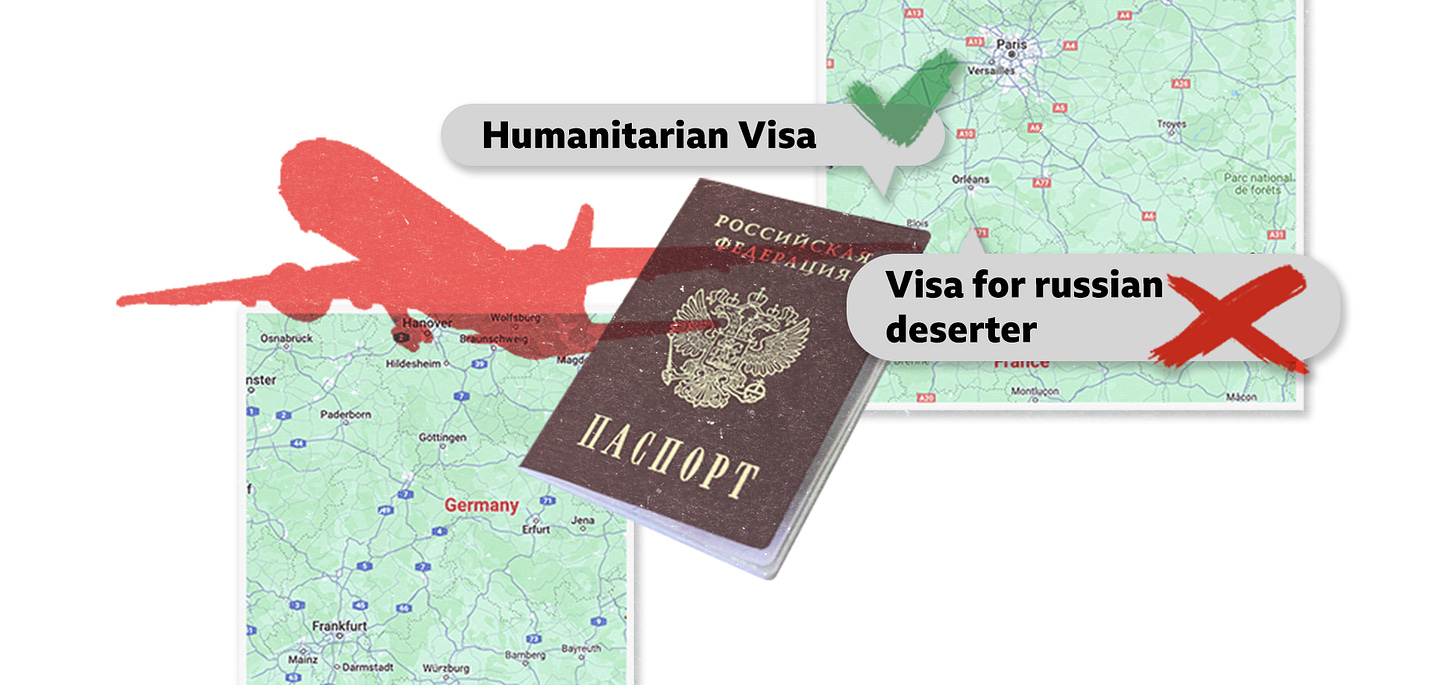

When the war began, some European countries, including Germany and France, started issuing humanitarian visas for Russians opposed to the war who might be persecuted at home. But deserters fall into none of the categories for such persons. Those who have managed to end up in Europe, whose stories were reported in the media, did so illegally or using existing travel documents.

Human rights advocates from organisations like InTransit, and France’s Russie-Libertés, have been lobbying European governments to admit anti-war deserters who have not been implicated in war crimes.

They are a "forgotten category of people,” according to Olga Prokopieva, the president of Russie-Libertés. She says human rights activists have been knocking on doors for a year, trying to work out at least some sort of system to assist those at greatest risk to leave Shanghai Cooperation Organisation countries (of which Russia was a founder, and Kazakhstan is a member) who are not involved in war crimes in Ukraine.

Last year, the French National Court of Asylum ruled that deserters from the Russian army and Russians fleeing mobilisation could be granted refugee status. The French news agency AFP reported in June this year that the court had granted refugee status to 102 men who fled mobilisation – but that there were no deserters among them. The reason is that you cannot file for asylum unless you are already in France. Without international passports, deserters have no hope of getting there.

A farewell to arms

After verification, Anton kept in touch with some of the deserters, whose numbers were increasing in Kazakhstan. "Some wanted to apply for asylum, some were looking for ways to legalise their status in Kazakhstan - and some wanted to move elsewhere,” he says. “We formed a community where everyone talks to each other, knows each other, and helps each other with advice and everyday matters."

Last summer, they launched the ‘Farewell to Arms’ project to show other Russian soldiers that there’s an alternative to taking part in the war. They recorded a video burning uniforms with the ‘Z’ letter sewn into them – including Anton’s uniform. So far, it’s the only video posted online: they are still in Kazakhstan, still with criminal cases against them, and still at risk of deportation.

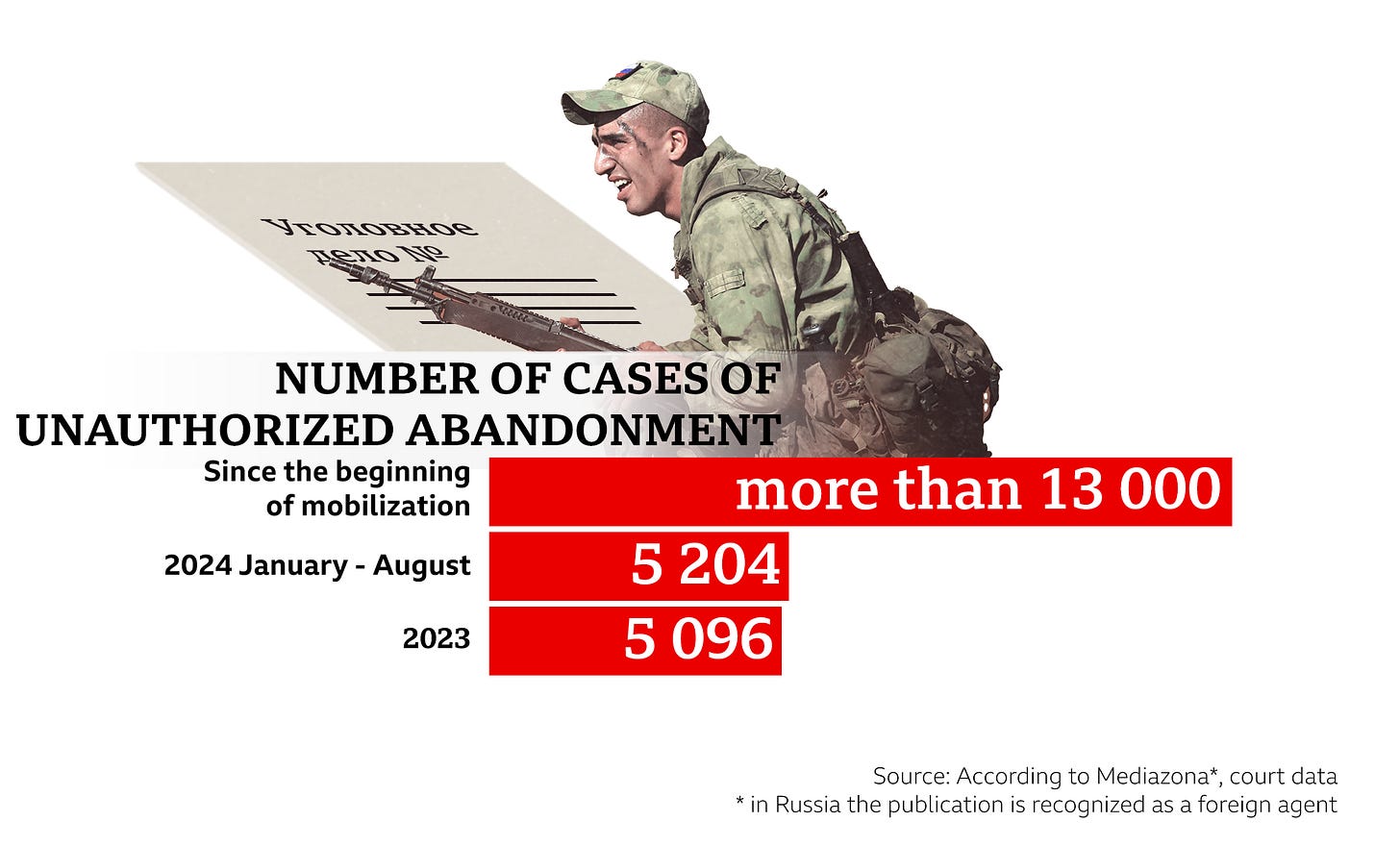

According to the ‘Mediazona’ news outlet, by August, roughly 5,200 criminal cases related to desertion were filed in Russian military courts this year – more than for the whole of last year. In total, since mobilisation began, over 13,000 cases related to refusal of service – absence without leave, disobeying orders, or desertion - have reached the courts.

"Desertion is a tough decision. I talked to some of my comrades who are now in Ukraine. They don't quit because they just don't see the point. Most of them are there for the money”

There are currently hundreds of Russian deserters in Armenia and Kazakhstan, according to Grigory Sverdlin, the founder of ‘Idite Lesom’ – Go by the Forest - an organisation that assists Russians who don’t want to participate in the war. These countries cannot be considered safe: in both, there have been cases of men fleeing the army who have been detained by Russian security service agents.

Anton and his colleagues continue to inform Russians about the option of desertion, via journalists or by directly reaching out to those at Russian bases or at the front. “I have personally contact them to convince them to flee Russia,” he says. “But they were very reluctant.”

"Desertion is a tough decision," Anton says. "I talked to some of my comrades who are now in Ukraine. They don't quit because they just don't see the point. Most of them are there for the money. Some can't handle the idea of being labelled as traitors and are scared of not being able to go back to Russia. Everyone has family in Russia, and some can't imagine life in another country. Many have never been abroad."

“As for some of the officers in my unit, they understand the choice precisely. If a man has been in the army for ten years or more, he’s a stone’s throw from his pension. If you’re not likely to be called to combat, it makes sense to sit out your service instead of deserting and go to some other country.”

After his escape, Anton kept in touch with some of his former comrades. They said they would have made the same choice as me. More than half of his platoon has been killed, they said.

The fact of desertion is not enough

Anton and five other men from Farewell to Arms were in May granted paperwork to enter Europe. “It doesn’t cover all the deserters in Kazakhstan, but it’s the first group case – six men at once,” says Artur Alkhastov. “We have been fighting for this since 2022, and finally we have some successes, even if only partial.”

Previously, only one individual case is known of a Russian deserter getting leave to enter Europe from Kazakhstan. He had retrained in IT, found a job, secured a visa, and left for Germany last summer.

Of the six men given visas in May, only Anton had served in Ukraine. The others were career officers and mobilised men. Together, the cases were clearly articulated and consistent, says Olga Prokopyeva of Russie-Libertés – the mere fact of desertion would not have convinced the European authorities.

Earlier this month, all six, including Anton, had reached France and were filing for asylum.

The number of requests for help coming to Go by the Forest continues to grow. In January 2023, fewer than 30 military personnel had asked from assistance. A year later, the monthly number of calls for support has grown more than tenfold.

"I have never regretted my decision to leave," Anton concludes. His family, however, were strongly opposed, and now see him as a traitor. "I tried for years to explain to them why I wanted to leave the army. Even after military operations started, I attempted to talk to them, but it was useless," he says.

Anton no longer speaks with his mother, and has stopped communicating with nearly all his other family members.

Read this story in Russian here.

English version edited by Chris Booth.

“My husband, the occupier"

The changing relationship of Russian military wives to the war in Ukraine – and to the men they love.

From the Moscow Conservatoire to death in a prison cell in Russia’s Far East

Pianist Pavel Kushnir’s fatal hunger strike went unnoticed as the West exchanged prisoners with the Kremlin.