“My husband, the occupier"

The changing relationship of Russian military wives to the war in Ukraine – and to the men they love.

By Oleg Boldyrev.

When Andrei brought his call-up papers home from work, Ekaterina tore them up. She immediately grabbed her husband’s passport and military ID from him, and thought about ripping them up, too. At the last moment, she stopped herself – a passport is too personal a thing. She thought she might break his leg instead. But that would mean involving other people: she wasn’t strong enough to do it herself.

It is hard to come by reliable sociological data in wartime. Building an accurate picture of how the relatives of Russian soldiers feel about the war is difficult. But some among them bear a triple burden: they are against the invasion of Ukraine; worried for the ones they love at the frontline; but they have stopped understanding their partners. The four women we spoke to for this story fall into this category. Their names have been changed for their safety but are known to the BBC.

In the end, Ekaterina gave back both the passport and the ID card, but when Andrei was about to head off to the draft office, she bolted the flat from inside. “I’m gonna rip the door off its hinges,” he warned. She backed down.

"Not because I was worried about the door,” she says. "If I could have been sure that it would make a difference, I would have stood my ground. But it seemed... how should I put it? That there was something fated about it. When the draft papers arrived, there was just no way out. To hide would have been shameful, unseemly, and beneath his dignity.”

Kristina lives in one of the southern regions of Russia that borders Ukraine. She was against the war from the very start. Russia agreed to the 1994 Budapest Memorandum respecting the territorial integrity of Ukraine, she recalls: “You can't first sign some paper, and then say ‘I changed my mind, let's forget it’. Or sell a car to your neighbour and then go to take it back because you don't like the colour the neighbour painted it. That’s just not right.”

Alexander, her husband, got his draft papers in September 2022. Prior to that, he had shown no enthusiasm for the frontline, and had convinced Kristina that everything would be dealt with by contracted professional soldiers and fighters from private military companies.

“He talked me through the weapons at Russia’s disposal, and how I didn’t understand a thing – it would all be over very quickly. I only said ‘just make sure they don’t call you up.’ In September, I reminded him of those words.”

Lena is 29, and married to Yevgeny, three years her senior. She says that the question of Ukraine didn’t bother her much in the run-up to the full-scale invasion in February 2022. The annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the fighting in the Donbas had caused a few minor inconveniences - because of the sanctions and Moscow’s counter-sanctions. But the topic didn’t really interest her. A few months into the war, she still thought there was bound to be a decent explanation for what was happening.

"And then, probably in the middle of the summer, it became clear that these were full-scale military operations, and I began to understand that this was not what they were telling us about on TV," Lena says. "After the mobilisation, I started to feel extremely negative about what was happening. Radically."

She had been living with Yevgeny for just over a year when the mobilisation was announced. He also thought running from war was shameful and difficult to do. And, Lena adds, he was used to trusting the state. To begin with, she had hoped his relatives might talk sense into him, but she was to be disappointed. “They just said ‘Oh, well, good for you! Have you packed your things yet?’”

Yulia and Igor met each other about three years ago. When he was 20, in December 2021, he signed a contract for military service and almost immediately found himself on the Ukrainian border. He told her he had been posted there for exercises. Initially they just wrote to one another, but in time their relationship grew closer – albeit mostly at a distance. Now they have a daughter.

“It started to seem that our president had been in power for far, far too long - and that everything was somehow a result of that.”

Yulia is three years older than Igor. She worked as a teacher before going on maternity leave in the spring of 2023. She shielded her students as much as she could from patriotic, pro-war activities, she says.

"When they tried sending us all these propaganda manuals, I ignored them as much as I could. I wasn’t going to push this nonsense we were forced to promote on the kids, I’m afraid. It was clear to me that I couldn’t change the situation fundamentally. But I could change it within the small circle I found myself in."

But with Igor, her husband, it was more difficult. On his rare visits home, conversations about what the Russian army was doing in Ukraine would often blow into arguments. A while back, they talked about whether Igor was ready to come back from the frontline if he was permitted. To start with, he said he was. Soon after, he informed Yulia he was the happiest guy in the world – with the best job, too.

She cannot tell if he was being serious or not.

The route chosen

Support for the war (or at least non-opposition to it) among those with relatives at the front is going down – from 70% in May 2022 to 59% in January, according to one piece of research. The independent ‘Chronicles’ project added that the proportion of convinced, motivated supporters of the war among relatives - those who oppose a ceasefire until the operational goals have been achieved - has also lowered over the same period: from 63% to 33%.

‘The Way Home’, a movement among wives of mobilised soldiers calling for their return, came to prominence in the autumn of 2023. Many of the participants were quick to state that they were not against the war itself – they simply wanted their husbands replaced with other military men and brought back home.

The interviewees in this article, however, are unequivocally opposed to the war.

Ekaterina and Andrei became friends in the late 2000s, and met playing football in their local neighbourhood team. They are from a village in southern Russia’s ‘Black Earth’ region. By the time they were married, Russia had annexed Crimea and the conflict in the Donbas was well underway. For Ekaterina, it remained nothing more than background noise. Questions about Putin, and the Russian state, came later when reforms to the pension system were introduced - and following another round of manipulated elections.

“It started to seem that our president had been in power for far, far too long - and that everything was somehow a result of that. Then I found out more about Crimea and what was happening there. It's not that I had a complete about-face, but I started to take more interest in what was going on and read more on the internet."

Ekaterina was not thinking about going to demonstrations. But she did feel Russia was moving towards dictatorship. She rarely talked politics with Andrei. “When he went to the polling station, I said ‘Make sure you don’t vote for Putin’. But elections are secret, so I don’t know who he voted for that time.”

During the March presidential vote, the re-election of Putin, Andrei was home on leave. She asked him to spoil his ballot. He said he had voted for one of the alternative candidates.

But in order to get leave to come home in the first place, she says, Andrei had to bribe one of the commanding officers – her guess is about $500, but she doesn’t know for sure. A few months ago, she lost her job in marketing. The only consolation, she says, is that she is no longer paying taxes to fund the war.

What would count as victory?

Kristina’s husband Alexander quickly found out that stories at the draft office about the newly-mobilised getting light duties guarding already conquered positions were false. Aged 30, he was soon at the front. He has been involved in regular ‘storm’ operations, but she doesn’t want to talk about the details of what her husband tells her about the assaults - or about politics in general. Fear seems to make her keep her sentences vague.

What’s clear is that she cannot see the point of the war anymore. "People went there with the understanding that they would achieve something and then come back home. But now it's not clear what's going on, and people don't understand — what are we doing here?” she says.

“There’s not even any explanation of what the goal would be that, if we achieved it, would allow them home. What would count as victory? Nobody knows. How many attack operations does a man have to survive before he can return home?”

In a year and a half of fighting, her husband has been on leave twice. When he gets back, he sits in the kitchen, drinks beer, and talks about those who didn't make it on the latest mission. Kristina listens. She says it's better for him to do this at home than elsewhere, where he might be drawn into a fight.

"We would sit, drink. I listened about the guys who died, who have left behind them wives, their kids, their elderly mothers. This utter hopelessness: he knows he has to go back, but doesn’t know what to do when he gets there. It’s a kind of despair. You want to help, but there’s nothing you can do. I sat and listened. A person needs to get this stuff out of their system."

Kristina talks abstractly about when she and Alexander disagree. "Recently, there was a very tragic event. Many people died. He said he supports the official explanation. I didn't contradict him, but hinted — maybe you should look at it from all sides? But he said: ‘No, it's the official explanation, you don't understand, and that's just how it is." She didn’t argue with her husband.

Yulia gets straight to the point, and names the event Kristina alluded to – the Crocus City Hall massacre in March, in which almost 150 people lost their lives. The attack was claimed by Islamic State: the Kremlin blamed it on Ukrainians.

"I said, 'Listen, how could it happen that the Crocus tragedy occurred, and our guys just completely took their eye off the ball?'” Yulia recounts a recent exchange with Igor.

“He replied, 'Where were they planning to go afterwards? To Ukraine!' To that, I said, ‘Sure, I get it now.' And then I honestly realised that his mind was so messed up already that the propagandists on the television can sit back and take a rest.”

Igor doesn’t pull his punches either. "You are stupid liberals! You are stupid pacifists!" he writes to Yulia on Telegram. After messages like that, Yulia decided to avoid talking politics with him. You can’t discuss disagreements without respect for each other, and her boyfriend has a problem with that, she says.

“He has this deep-seated belief that other countries want to destroy us, and that we are beseiged by enemies.”

Both women say that war has changed their men completely. Yulia says Igor used to be chatty, responsive, knew when to listen and when to reply. Now the communication is in monosyllables: ‘Yes,’ ‘No,’ ‘Fine.’

To begin with, she thought her boyfriend was giving up on being a father. Then she found out he was barely talking to his own parents, either.

When it comes to this, Kristina speaks directly: "The person who was called up in September 2022 and the person who has been involved in combat in 2024 are two completely different people. I could argue with my beloved man, who loved me back, and was by my side. We used to have good conversations, and a quarrel would end quickly. Now, a quarrel can just keep going and going. You can express an opinion, but you shouldn’t argue or try to prove a point - because you might prove something he doesn't want to hear."

Come and see

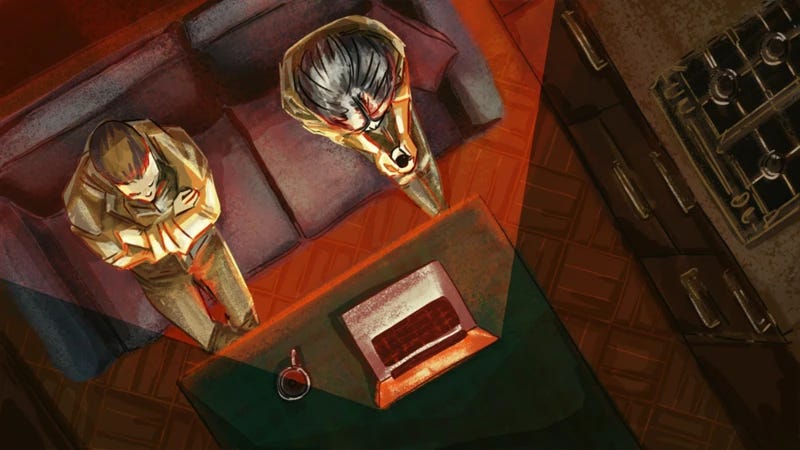

“20 Days in Mariupol”, a film about the destruction of the Ukrainian port city, won the Oscar for best documentary in February. When Andrei came home on leave in march, Ekaterina found a copy on YouTube and set up her laptop on the table. “Come and see,” she said. Andrei didn’t resist. He came over, and they sat on the sofa to watch the film.

He watched about half of it. But what Andrei saw did not shake his beliefs. “He believed what he saw on the screen, that the events were tragic, that others were suffering, peaceful people, and it should not have happened,” she says.

“But he still said something like ‘It’s not our fault: they set it all up.’ He has this deep-seated belief that other countries want to destroy us, and that we are beseiged by enemies.”

Lena has given up trying to talk with her husband about supporting or condemning the war. "Usually, it turns into a colossal shouting match. The last time we talked about this was probably in winter."

Instead, Lena keeps her focus on the lies and chaos that go with conscript life. Her husband doesn’t argue with her on this. Lena says he now believes the ‘special military operation’ was a huge error.

She thinks her husband is gradually realising that if they've been lied to so many times about the details, then it’s probable the overall explanation of why Russia is fighting in Ukraine in the first place is untrue, as well.

“I don’t ask him point blank – ‘Don’t you think this is all crazy?’ But I can raise it indirectly - to avoid a major blow-up. He still thinks I am having a go at him, though.”

‘2024: The Year of the Family’

Kristina and Alexander met on social media. He messaged her after he saw a comment under some post. Before being conscripted, he worked in a warehouse for a big retailer, filling orders. She was 33 and a preschool teacher. She had a daughter from a previous marriage, but she and Alexander had not been able to have a child together. By September 2022, when mobilisation was announced, she had gone through the preparation for IVF treatment.

"And just as that was completed, my husband was called up. So I had to forget about everything, put it on hold. Whether we'll have a child or not, I don't know," she says with bitterness.

The ‘Year of the Family’ declared by Putin in 2024 seems to Kristina "like a slap in the face." On top of everything, she has found a tumour that she thinks could have flared up because of the stress of her husband being conscripted. She needs surgery, but there is nobody to leave her daughter with.

Kristina walked out of her preschool job that autumn after arguing with colleagues about the mobilisation. They told her not to get worked up, and that it was right that her husband was at the front. It was particularly tough to hear this from people whose relatives had not been called up, she adds.

When he came back on leave in autumn 2022, Igor said to Yulia he would like a child. She thinks the idea came to him when one of his young comrades was killed. She was so in love she didn’t hesitate for long. She conceived during his next trip home, during the first winter of the war.

Late last year, Igor and Yulia went to register the birth of their new-born daughter. In the adjoining booth, another woman was filing for divorce. She was loudly explaining to the clerk at the desk that her husband had become unbearable during his rare visits home from the fighting.

“At that moment, we were sitting side by side. I looked at Igor, and he was expressionless. I thought to myself ‘Damn, it’s so sad that so many families will be broken’. Because in the heat of the moment you can say a lot of harsh things,” Yulia says.

"My thoughts are only about what is happening to my husband right now, and when he will call - or if he will call. And yes, I am scared all of the time. I mean, the fear doesn't go away, I can't get used to it: it doesn't ebb at all."

“Honestly, when I heard her, I just wanted to go up to the girl and hug her, and say ‘I totally understand you’.”

News of the death in prison of the opposition leader Alexei Navalny came on February 16th, Yulia’s birthday. She had been to the hairdresser because she was expecting guests that evening.

"So I was in this taxi, feeling good, writing a post about how beautiful and elegant I felt. Then I read the news, and my expression changed within a minute. It was a pretty serious shock because when Navalny was alive, there was at least some hope still."

Igor’s response in the chat was ‘Well, he’s snuffed it then.’ And added that his death was a message to the Ukrainians – it’s time to surrender. When Yulia said Navalny and Ukraine were totally different matters, they ended up in another argument.

The curve of fear

Kristina’s husband writes to her when is deployed on another assault. The silence in their correspondence that follows can last a week or two. The curve of fear rises and falls. Once they were without contact for almost two months, and she began searching for Alexander, phoning his unit or calling up the hotlines where information about the dead and wounded is collated.

For Ekaterina and Andrey, things are different. Communication with her husband cannot be counted on. He does not write when he goes to the front. He only tells her when he’s back.

"My thoughts are only about what is happening to my husband right now, and when he will call - or if he will call. And yes, I am scared all of the time. I mean, the fear doesn't go away, I can't get used to it: it doesn't ebb at all."

On June 1st, it was Children’s Day, so Ekaterina took the kids to the park for a concert. There was an aid collection point to support frontline soldiers. A banner with some children’s drawings and a hackneyed line from a song about ‘the sun, the sky, and mummy and me’. And a man in camouflage with a limp, leading a little girl through the park. It felt like the apotheosis of modern Russian fatherhood, Ekaterina says.

There were speeches from the stage by officials, talking about patriotism. Ekaterina’s daughter rolled her eyes and asked why they had to listen to all this. In the girl’s school, there are not many such lectures in the ‘Important Talks’ lessons. Still, Ekaterina reminds her not to take them seriously - and she calls her reminders ‘vaccinations’.

When Ekaterina talks of her husband, she sometimes slips and says ‘if he’s still alive’. The constant thought that Andrei may die at any moment is draining her. From the moment he was conscripted, and despite the promises that mobilised men would not be sent to the front, Andrei was immediately deployed to one of the flashpoints in the Donbas.

"Back in October 2022, I just wanted to jump out the window. I mean, everything was as bad then as it is now, but I just... I don't know, I'm waiting for something. I'm waiting for this all to end somehow,” Ekaterina says.

“But back then it was just full-on drama. Maybe you could make some kind of B-movie from it that no one would watch. It's a personal drama for everyone involved – how can you put it into words? It’s just a total catastrophe.”

When Kristina is asked if she discussed desertion with her husband, her answer is evasive: “Everything has been discussed.” Some conscripts cling to the hope that one day they will be sent home. "Most of them are like that: they conjure up imaginary dates, and he does, too,” Kristina says.

“First it was some upcoming speech by Putin — ‘he'll let us go’. He didn't. Then it was the anniversary of mobilisation — ‘surely they'll let us go’. They didn't. Then February 24th, the anniversary of the start of the 'special military operation’. Then May 9th, Victory Day. You calm yourself down with these vague dates in the future when they will let you go. And they will not!”

Her husband has lost the strength to decide what to do. When he came back from another assault operation, she said ‘You’ve been stood in a queue, and one day everyone will get to the front of it. I don’t know why you’re standing in line so obediently.’

“I don’t know what sort of man will come back”

Ekaterina has often told her husband that he is an ‘occupier’. Andrei has stopped even arguing about it. She doesn’t think the word offensive. To Ekaterina, it’s just a fact. What’s more difficult is whether he should be called a ‘killer’.

“It’s a bit like saying a train driver who happens to run over a suicide, like in ‘Anna Karenina’, is a murderer,” she says. She considers her husband held captive by the Russian defence ministry. “It’s as though there’s an engineer standing behind him with a gun to his head, commanding ‘Drive! Don’t stop!’ And on the tracks, there are hundreds of Anna Kareninas.”

Lena says that the occupier is the state that led Yevgeny to war. But it doesn’t free her from the heavy burden of thought.

"When we argued, I thought: how can I even live with someone who has such views? He has probably..." and she pauses. "His actions have probably caused the deaths of some people. How can I continue to live with such a man?"

“I can only live with what is happening this moment - you can try to analyse the past, and future remains unknown. But whatever happens: no good will come of it. You can come up with a million different endings, but I don’t think any of them will be happy.”

Lena’s verdict, though, is that her husband is simply among those who have made an honest mistake. But a rapist, murderer, or marauder? She cannot imagine him as that.

Along with Ekaterina and many other wives of conscripted soldiers, Lena petitions the Ministry of Defence to demand the return of their husbands and try to arrange meetings with military officials - so far, unsuccessfully.

Among her relatives, there are some who are not against the war - they simply think it should be conducted by other soldiers. Lena does not communicate with them.

Once, Kristina asked her husband if he had killed anyone during his assault operations. Alexander avoided giving a straight answer. He said he could see the enemy clearly through the sights of his gun, but he didn't know if people had died from his fire.

What about when assault troops enter territory Ukrainian soldiers have retreated from? To this question, Kristina responds with what Alexander has recounted: "When our guys advance to positions, in most cases there's no one there, just mines and trip wires. And then we get bombed from drones. On the other side, everything is done to save men’s lives. It’s organised that way."

When asked how she copes with the idea that shots fired by Alexander may have caused someone to be killed, she says, “"We are all human, no one wants death. We don't wish it on anyone. But sometimes it’s either them – or it’s you.”

Soon after her boyfriend ended up in Ukraine, Yulia spoke with him about the torture meted out by ‘Wagner’ mercenaries in Syria. The conversation came to an end when Igor tried to justify the brutal treatment of Ukrainian prisoners – they started it, supposedly, by mistreating Russian soldiers. “I told him it was unacceptable in either case. Violence for me is the very worst thing there is.”

She hopes Igor will come back from the frontline uninjured, but isn’t making plans. "I don't live in a fantasy world, I can't say he'll return and ‘we'll live happily ever after’...” Yulia says. “I don't know what sort of man will come back."

Ekaterina mulls all that has happened during the war, before and after her husband’s conscription, and considers it a disaster. It doesn’t matter what happens: she is certain her family has nothing to look forward to.

“I can only live with what is happening this moment - you can try to analyse the past, and future remains unknown. But whatever happens: no good will come of it. You can come up with a million different endings, but I don’t think any of them will be happy.”

Read this story in Russian here.

English version edited by Chris Booth.

Graphics created by BBC Russian Visual Journalism.