“Victims of Disappearance”: Why it’s so easy for detainees to go missing in Russia’s prisons

The rules that allow a prisoner’s location to be kept secret during transit often can be used to put pressure on the detainee — almost always a political prisoner, as it suits the Russian authorities.

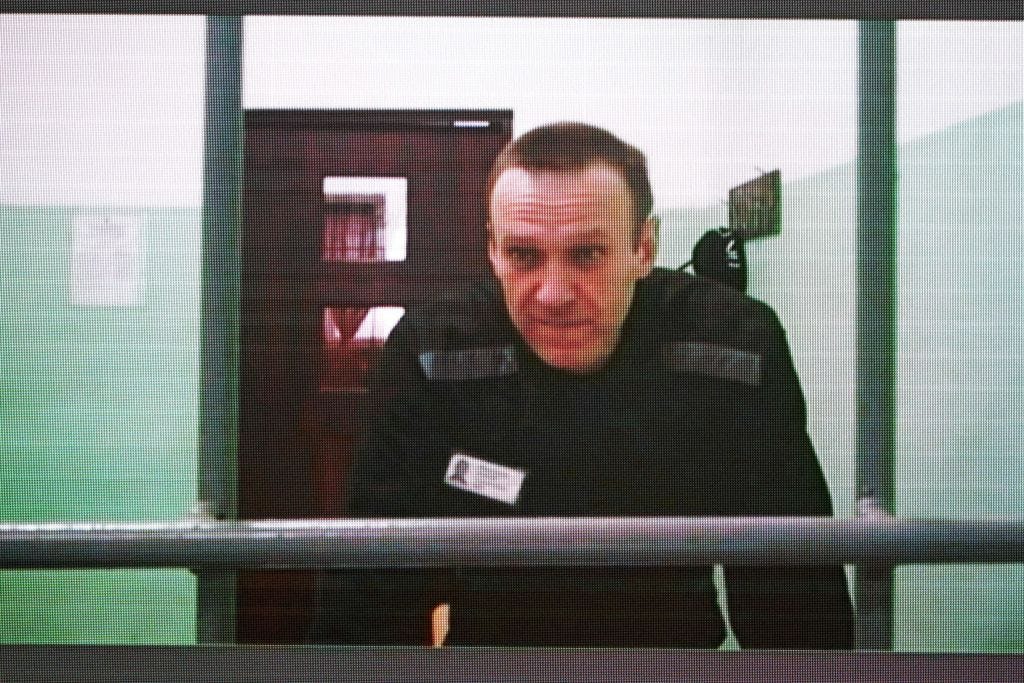

The appearance in an Arctic penal colony of Russian opposition figurehead Alexei Navalny after more than two weeks in which his supporters lost touch with him has focused attention on how easily detainees can get lost in the depths of the country’s prison system. The rules that allow a prisoner’s location to be kept secret during transit often simply suit the logistics. But secrecy can also be deployed to put pressure on the detainee: human rights activists call it “enforced disappearance.”

“The authorities are not obliged to say where a prisoner is being taken to,” says Natalya Taubina, the head of the human rights fund 'Public Verdict' (declared a ‘foreign agent’ in Russia). “But the rules speak of restricting such information for security reasons. Which means transits can last for weeks or even months, leaving the prisoner in complete isolation.”

There have been more and more such reports in recent years – and almost always involving political prisoners.

The prevalence of 'political' disappearances in the statistics may also be explained by the fact that their fate garners attention from human rights activists. Close contact with lawyers ensures such disappearances in transit are flagged up.

Andrey Pivovarov, the former leader of ‘Open Russia’ (deemed an ‘undesirable organisation’ by the Russian government), is a recent example of the prolonged ‘disappearance’ of a political prisoner from contact with lawyers and relatives. A court in Krasnodar sentenced him, in July 2021, to four years in prison for his involvement in the organisation’s activities. In December 2022, after his appeal, he was transferred from pre-trial detention to an unknown destination.

In mid-January, Pivovarov made contact from pre-trial detention in St. Petersburg – before disappearing again for a month. Statements and appeals from human rights activists were to no avail, and it wasn’t until February 20th that Penal Colony No. 7 in Karelia finally provided information about his whereabouts: prison staff admitted to his mother that he had been there since January 24th. Pivovarov had been put in strict isolation on arrival, which meant he couldn’t contact anyone.

"In international law, such conditions are generally referred to as 'enforced disappearance' — the person is held in isolation, under the complete control of authorities, and at high risk of torture, cruel treatment and arbitrary action. They have no way of complaining about it, let alone reporting it," says Taubina.

Right now, the whereabouts of former Moscow municipal deputy Alexei Gorinov, convicted in July 2022 for speaking out against the war in Ukraine, remain unknown. 62-year-old Gorinov had been held in Penal Colony No.2 in the Vladimir region, and in early December had complained once again about feeling very unwell.

His lawyer visited him and sounded the alarm — Gorinov looked so bad that he couldn't sit or speak. That was December 8th, and the last time anyone saw him. The lawyer has not been allowed into the colony since, and Gorinov's location is now unknown.

(It’s possible he has been transferred to a hospital outside the prison camp but there’s no obligation on the Russian Federal Penitentiary Service (FSIN) to divulge such information.)

The UN Special Rapporteur on human rights in Russia, Mariana Katzarova, issued a statement on the case: "Alexei Gorinov has become a victim of enforced disappearance. As with Alexei Navalny, the enforced disappearance and the detention of Gorinov without communication with the outside world, which is tantamount to torture and cruel treatment, puts him at risk of further human rights violations, including loss of life."

But it’s not just political prisoners who are fated to go off the radar for long periods of time.

Dmitry Vedernikov was serving a 22-year sentence for his part in murders and robberies committed by an organised criminal group. In January, he was transferred from Chita to a penal colony in Krasnoyarsk in Russia’s Far East. Subsequently, the transfer from Krasnoyarsk was changed. It took nearly three months for Vedernikov's wife to find out where he was: on March 15th, he showed up in a prison colony in the Tula region, not far from Moscow, at the other end of the country.

Railway zigzags

One of the simplest explanations for the prolonged transfer of prisoners during transit is that the process is carried out by rail. So-called ‘Stolypin’ carriages are hitched to regular passenger trains. The cars have no windows, but have bars separating the corridor from six berths. These may be overcrowded with two to a bed. And the route may not be direct.

"Prisoners are gathered from different places to a transit zone. Some of them are put in the carriage which is hooked up to a train heading in roughly the right direction - to where they are supposed to serve their sentence, or where they’ll be held in pre-trial detention for further investigation,” explains Taubina. “There can be all sorts of zigzags and stops along the way.”

It took 35 days for Roman Khabarov to reach prison from the town of Voronezh. A former police officer, he gained attention in the early 2010s after giving interviews about the corrupt state of the local law enforcement agencies. He also participated in opposition rallies, including the famous "March of the Millions" at Bolotnaya Square in central Moscow, and had also engaged in human rights work.

In 2014, he was arrested for allegedly organising illegal gaming rings - an accusation he describes as entirely baseless. A lengthy legal process concluded in Voronezh in November 2018. Before his appeal, Khabarov was placed in pre-trial detention in Samara. He was then moved to Syzran. When the appeals court delivered its verdict and the sentence took effect, he was taken back to Samara. From there, to Ulyanovsk. Later, through Kazan and Izhevsk, to Yekaterinburg.

"Neither common sense nor practicality can explain prison service logistics," says Khabarov. "People next to me during the transit were traveling from Rostov to Voronezh through Samara, from Moscow to Samara through Voronezh, or from the pre-trial detention centre in Novorossiysk to Syzran." In his case, he says, there was no malicious intent, or attempt to delay him during the transit.

"Transit in Russia is a sophisticated, protracted, and clandestine form of abuse against prisoners and their families."

But things can be very different.

"There are times where force, beatings and torture are used during transit. In such cases, the transfer is drawn out until the traces [of mistreatment] vanish," says lawyer Irina Biryukova, who has worked on cases of torture of prisoners. "A guy gets held up in transit, kept out of sight, and kept on the road for a while longer.”

With food, medical treatment, and communication even more limited than in prison, the transit itself can serve as an instrument of coercion.

"There are cases when they intentionally put in transit important witnesses - or those who have refused to become witnesses, but whose testimony is required," notes Biryukova.

"Putting pressure on them in prison might lead to the prisoner informing relatives or lawyers. That’s a controlled process. But during transit, everything’s beyond control: they can 'ride' that person, deliberately worsening conditions, withholding medication and food, denying access to the toilet, and so on. And there’s no time limit to it — they can ferry them around for as long as they want."

“A sophisticated, protracted, and clandestine form of abuse”

Some of the best-known incidents of disappearance during transit in recent years are associated with high-profile cases.

In the summer of 2018, during transfer from a prison in St. Petersburg to a pre-trial detention centre in Penza, two defendants in the ‘Network’ case, Viktor Filinkov and Yuri Boyarshinov, disappeared for a month.

In October 2021, there was a two-week period of silence regarding Maxim Ivankin, who by that time had already received a sentence in the same case but was now under investigation on suspicion of murder.

After Filinkov's court hearing in St. Petersburg, where he was sentenced to seven years in prison, he was transported to a facility in Orenburg. It took 45 days, via Vologda, Kirov, Yekaterinburg, and Chelyabinsk. Filinkov’s defence lawyer, Yevgenia Kulakova, catalogued the ordeals of the journey in an essay for ‘Mediazona’ (an outlet designated a ‘foreign agent’ in Russia).

"Transit in Russia is a sophisticated, protracted, and clandestine form of abuse against prisoners and their families," she wrote.

In early 2022, a lawyer spent a month searching for Roman Pichuzhin, one of the convicts in the ‘Palace Case’ that followed protests sparked by Navalny’s film on the colossal estate allegedly built for President Putin on the Black Sea coast.

At the beginning of last year, Rinat Nurligayanov disappeared for three weeks. He had been convicted for involvement in ‘Hizb ut-Tahrir’, an Islamist movement recognised as a terrorist organisation and banned in Russia. His disappearance coincided with the consideration of his appeal in the European Court of Human Rights. (He had received a 24-year prison sentence in 2018.)

And on September 4th of this year, opposition activist Vladimir Kara-Murza, sentenced to 25 years behind bars, was removed from a pre-trial detention centre in Moscow. Seventeen days later, his lawyers found him in strict-regime Colony No. 6 in Omsk, in Siberia.

Getting word out isn’t easy

Detainees search for ways to communicate in transit prisons. Doing so through authorised channels is difficult due to their temporary, transit status.

"We spend the night in a pre-trial detention centre, and even our personal files aren't there,” explains Khabarov. “We are just temporary residents: our cases are closed until the next stop in the transit. So nothing is allowed, just in case.”

It’s possible to try one’s luck and make friends with cellmates who might have a mobile phone hidden from the guards. Some of Biryukova's clients managed this way to convey a message to her, or to their families, about their whereabouts.

"When it matters, the system is well organised. When it matters, not even a mouse can slip through."

But she stresses that political convicts, along with those deemed important to an investigation, or to the prison system itself, are likely to be isolated during transit. The prison authorities will ensure they are completely deprived of any way of communicating.

"So that the lawyer isn't waiting right at the gates, so that the media aren't making a fuss, so as not to attract unnecessary attention to the prison colony.”

“This way, information about their arrival at the camp only becomes known 10-12 days after quarantine. Except for the staff, no one would know they're there," explains Biryukova.

And then there are entirely separate rules for the most famous political prisoner in Russia: Alexei Navalny. By arresting the lawyers who had worked with him for many years, and almost entirely cutting off communication with the new defence team, the authorities ensured that information about Navalny’s movements wouldn't leak from the transit or via the prison staff along the way.

"When it matters, the system is well organised," comments Biryukova. "When it matters, not even a mouse can slip through."

Read this story in Russian here.

English version edited by Chris Booth.

BBC is blocked in Russia. We’ve attached the story in Russian as a pdf file for readers there.

“I assume they tortured him and overdid it.” Espionage, China, and death behind bars in Russia’s Far East

The story of Sergei Yatsenko — one among a growing number of treason cases opened in Russia in 2023.

Russian police: burnt out, disappointed and confused

Since the start of the war in Ukraine, Russian police officers are abandoning the force in droves to become taxi-drivers, couriers, or cashiers.