LONG READ: The fight for Hostomel airfield. How the gates to Kyiv stayed locked

The untold story of the battle that changed the course of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

By Oksana Torop and Svyatoslav Khomenko.

Evening had set in on Wednesday, February 23rd 2022, and National Guardsman Ruslan was on duty with seven other men stationed alongside the runway at Hostomel airfield outside Kyiv. (We have changed his name and that of some others interviewed for this article to protect their safety.)

During the day, members of the military command had come to check on the situation but by now they had left. Outdoors it was cold, and a wind was whistling. The lads lit a campfire, huddled close to get warm, and started grilling sausages.

The last An-124 transport plane took off from the airfield at 11 pm. The national guardsmen breathed a sigh of relief and, smelling a little of smoke from the fire, made themselves comfortable in their ‘Varta’ armoured vehicle.

"I got myself nicely settled in. I thought, I'll do my sentry duty, then get a bit of sleep. But in the end..." – 22-year-old Ruslan pauses. He gathers his thoughts, wanting to tell us in detail precisely what happened on February 24th at this airfield just 25 kilometres northwest of the capital.

We walk together through the abandoned grounds, where the wreckage of the destroyed ‘Mriya’ - once the largest transport aircraft in the world - still rests. A lot of evidence of Russia’s invasion remains.

Here is the charred administration complex, where the debris of broken windows and shattered structures still lie. A little further on, we can see destroyed planes, and the marks of explosions on the super-strengthened concrete runway. Next to the airfield, behind a fence, is a huge dump of burned-out and rusting Russian military equipment. Ukrainian soldiers are gradually dismantling it and ferrying it away.

Even two years after the full-scale Russian invasion, you could still make a film about the apocalypse on this vast, disfigured, military expanse. The uncharacteristic silence of the airfield, sometimes broken by blasts of wind, puts you on edge.

From a military point of view, ‘Antonov’ – the other name for the aerodrome, after the aircraft manufacturer that was based here - was a strategically vital target for anyone wanting to surround and capture Kyiv.

In the past two years, there have been a good many reports about the battles for Hostomel. We have tried to focus on previously unknown details, to paint a complete picture of what actually happened here. We collected testimonies from eyewitnesses, both military and civilian, as well as information from government representatives, the military command, and experts in the field.

What was happening before the invasion

Citing western intelligence, foreign media started reporting in autumn 2021 that Russia was preparing for a full-scale invasion of Ukraine. The first among them, in October, was the Washington Post. It noted Russia's movement of a huge amount of military equipment and personnel to the Ukrainian border. "This doesn't look like exercises," western experts said.

Later, the imminence of a Russian assault on Ukraine was openly discussed by western leaders. On February 18th, 2022, Joe Biden stated during a briefing: "The U.S. has reason to believe that Russia will attack in the next weeks or days. Putin has made the decision."

To say the Ukrainian authorities reacted to the Americans' warnings in a reserved manner is an understatement. Members of President Volodymyr Zelensky's inner circle, government officials, and MPs from the ruling party in parliament explained away to journalists and business the West's behaviour as a consequence of its geopolitical confrontation with Russia: Ukraine was just caught in the crossfire. Separately, government representatives also discouraged escalating the situation in the public domain in case it led to the withdrawal of investors from the country.

Even Zelensky offered his personal reassurance to Ukrainians. On January 19th, he delivered an address (back then they were not yet daily), a phrase from which turned into a meme. Regarding the preparation of Ukraine for war, he said: “In May, as always, we’ll light barbecues.”

In mid-January, CIA Director William Burns secretly travelled to Kyiv. Western observers would later regard his meeting with Volodymyr Zelensky as decisive: it was here that he told the Ukrainian leader in detail about Russia's precise plans to attack his country.

Burns later shared details of the conversation with Politico:

"I saw Zelensky in the middle of January to lay out the most recent intelligence we had about Russian planning for the invasion, which by that point had sharpened its focus to come straight across the Belarus frontier — just a relatively short drive from Kyiv — to take Kyiv, decapitate the regime and establish a pro-Russian government there,” Burns said.

The CIA director spoke “with some fair amount of detail, including, for example, the Russian intent to seize an airfield northwest of Kyiv called Hostomel, and use that as a platform to bring in airborne forces as well to accelerate the seizure of Kyiv.”

In the same article, Burns described Zelensky's reaction to his words: "He was in a bind. I was very impressed with him then, but I could understand the predicament he was in, too. He did not want to spark an economic or political panic in Ukraine. He was cautious about taking steps like a full mobilization of the Ukrainian military that Putin could then seize upon as evidence of provocation. But he was clearly sobered.”

We asked the President's Office whether the CIA director did indeed specifically warn about Hostomel during the visit, and what the outcome of the conversation was, but our request went unanswered.

The American journalist Simon Shuster, who had exclusive access to President Volodymyr Zelensky during the first year of the war, and has described his impressions in the recently published book "The Showman," tells a different story. Shuster writes that Burns didn’t manage to win over Zelensky:

“To him, the Russian plan did not involve enough troops to occupy a city of four million people. Zelensky expected many of his citizens to rise up and resist. Besides, the U.S. intelligence looked inconclusive to him. It appeared to spell out one of Russia’s options, perhaps the most aggressive one, but not the likeliest... In all their interactions over the years, their phone calls, summits, and peace negotiations, Putin struck Zelensky as cold and calculating, bitter and aggrieved, but not insane, not genocidal.”

According to our information, strengthened security at airfields, including Hostomel, was indeed discussed at one of the meetings of the National Security and Defence Council ahead of Russia's full-scale invasion. In any event, it is likely that the Ukrainian authorities had intelligence on the possibility of Russia landing paratroopers into Hostomel.

A convenient airfield

Kyiv’s American partners paid special attention to the airfield in Hostomel with good reason. Its infrastructure allowed the landing of large aircraft, which is why the world's largest transport plane, the ‘Mriya,’ or ‘Dream,’ was hangared there. And large aircraft means not just civilian planes but also military transport planes capable of carrying a huge number of troops and military materiel.

Adding the geographical factor — Hostomel is located some 25 kilometres from Kyiv — all the pieces of the puzzle come together.

Two years on from the start of the full-scale invasion, military experts are in agreement: capturing Kyiv in the shortest possible timeframe was Russia’s top objective. For this they had a simple plan.

The first wave of paratroopers was supposed to rapidly capture the airfield in Hostomel and prepare it to receive the main force deployment. This would arrive at the airfield in a second wave, aboard Ilyushin-76 transport planes belonging to Russia’s Aerospace Forces. Hostomel’s location meant they could advance on Kyiv both from the north, towards the Minsk resudential area and Obolonskoye, and from the west towards Svyatoshino.

Experts believe a mirror operation was due to take place to the south at a military airfield in Vasylkiv, 30 kilometres from Kyiv. Be that as it may, it was all supposed to start with Hostomel.

Had the operation to take Hostomel been successful, those we have spoken to say around 5,000 Russian troops would have appeared on the outskirts of Kyiv on tanks and armoured vehicles. More would have joined them daily from the direction of Belarus, travelling through the Chernobyl exclusion zone, and via the road linking Zhytomyr and Kyiv regions. In this way, virtually the whole of the capital would have been brought within range of Russia’s artillery.

Given all this, encircling and capturing Kyiv, which in February 2022 was, to put it mildly, underprepared for full-scale combat, should have been a mere technicality.

The ‘Lions’ of the 4th Brigade

The defence of the strategically important airfield was to be taken care of by the 4th Brigade of Ukraine’s National Guard, which was based at Hostomel.

The brigade was created from scratch in 2015 for front line combat operations, according to Andrii Kulish, its press officer. In 2023, it was named ‘Rubizh’ to mark its distinguished service in the fighting for Rubizhne in Luhansk, and fighters from the brigade were involved in other flashpoints on the eastern front.

Kulish recalls constant alerts in the unit in preparation for an invasion, with brigade members training hard in readiness to fend off attacks – though the expectation was of an escalation of fighting in the Donbas instead.

The most combat-ready part of the brigade, several hundred contract soldiers, was sent in December 2021 to the Yavoriv training ground in Lviv region for combat coordination. After two months of training, on February 20th, 2022, they were sent on rotation to Luhansk region without even stopping in Hostomel. It meant that military unit 3018, located beside the airfield, numbered only a few hundred men, mostly conscripts and admin staff.

"The 'Lions' (contract soldiers) had departed. There are maybe a couple of hundred conscripts left. They haven't served for very long. They haven’t gone through the same tough training program as the contract soldiers. They were taken out to fire off a few rounds at the range, but you can’t say they’d had enough time,” says Ivan, one of the brigade’s professional soldiers (name changed).

“They’d be used to load trucks, or clean something, or they’d be sick, or they’d stand on duty at some checkpoint.”

Ivan’s duties meant he wasn’t sent on to Luhansk, but immediately returned to Hostomel from the Yavoriv training ground. He’s certain that Russian intelligence were aware that there were only draftees left at the airfield.

“They needed the runway to land their Ilyushins, and they were sure they could take it easily.”

"No reason to panic"

We know from employees of the state-owned Antonov aircraft manufacturer, which owns Hostomel airfield, that an American delegation visited the facility in January. It included diplomats, CIA staff, and members of the US Defence Intelligence Agency. The goal of the mission was to assess the vulnerability of the airfield in the face of a potential Russian invasion.

In February, according to our information, Ukrainian security service officers visited the airfield. They installed surveillance cameras with autonomous power supplies across the territory, transmitting images in real time over the 4G network. People we spoke to said these cameras were damaged a few hours before Russia attacked. It’s still not known who did it.

Military personnel who were serving at Hostomel say nobody warned them of a possible Russian airborne operation, and they found out about US intelligence data only after the invasion started – and even then only from the press. The soldiers talked among themselves about how their command wanted them at the airfield to dig fortifications, but the civilian administration of Antonov wouldn’t allow it, for fear of damaging underground communications cables.

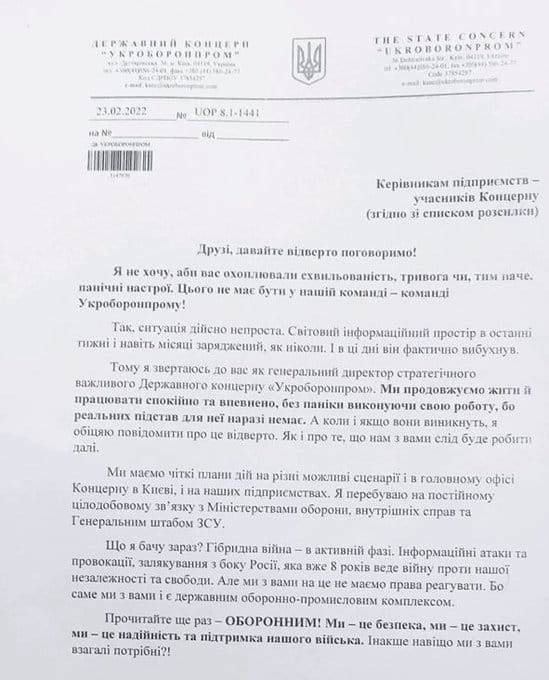

On February 22nd, Ukraine’s military-industrial enterprises received a letter from Yuri Gusev, the head of Ukroboronprom, the state armaments agency. We have seen a copy. It’s written in a reassuring tone. Gusev urges workers to go about business normally and not to panic:

"We keep on living and working calmly and confidently, carrying out our jobs without panicking, because there are no real reasons for it now. When and if they arise, I promise to be honest about it," said the letter received by Antonov less than a day before the start of the invasion. It went on to urge workers “not to believe in fakes,” to “stop spreading rumours,” and to cease following social media messages.

"Few people in this country today know more than we do," the letter said. It stated that Ukroboronprom had a clear plan of action for different contingencies. It turns out the details of the plan were never disclosed, either before or after the invasion.

So life went on as normal at the Hostomel aircraft factory: there was no increase in security; not there nor at the aviation giant’s other aerodrome in the Kyiv district of Svyatoshyno.

Nothing special was going on at the national guard base near the airfield, either. Conscripts had only a few weeks earlier been stationed across the airfield grounds. Some anti-aircraft installations were brought in and the soldiers were issued with ‘Igla’ man-portable air defence systems, or MANPADs. The unit’s command itself visited to get an update on the situation a few days before the invasion. The soldiers were told nothing.

Ruslan, the national guardsman, admits he had a sense that something was afoot, but like his comrades, he didn’t believe in an invasion till the very end.

"We all tried to think logically: there was no sense in it. I thought that a broad offensive could start with the Donbas, but not with us. No one expected that in a few hours they would be in Hostomel."

And so, on the evening of February 23rd, the lads who had just come off duty at the airfield lit a bonfire, grilled some sausages, and settled down for a nap in their nicely warmed-up armoured car.

The start of the invasion: "We just sat there and watched the news"

At about four o'clock in the morning on February 24th, Russia launched the first massive rocket attack across Ukraine: more than 50 missiles were fired, mainly at airfields, warehouses, and other military infrastructure. There were also strikes on civilian targets.

National guardsman Ruslan had been allotted sentry duty from four to six in the morning. He climbed out of the Varta armoured vehicle, and took his position on the roof of a single-story building at the airfield. He heard the noise of the rockets flying over his head towards Kyiv.

"I immediately knew these were missiles, not aeroplanes. I got scared for some reason. I lost the ability to speak, and couldn’t transmit over the radio properly,” he recalls. The order he received was to observe the situation.

"Then we climbed down from the roof, started waking everyone up: the war has started! We started calling our parents..."

The combat alarm was sounded in the unit at around five o’clock in the morning. The guardsmen distributed kit and regular weapons – pistols and rifles.

About a quarter of those who arrived at the unit were involved with admin work: accountants, clerks, HR staff, mainly women.

“Everyone’s in a state of shock. Let’s get the girls out of here, hide them somewhere, the ones who’ve come to work. They were weeping...” Ivan tells us. Later they sent the women home and told those on their way to Hostomel to go back.

Because it was an international airfield, a small border guard unit was also based there. They were also mobilised. Sergei was at home that night. “They called me about five in the morning and told me to get to the airfield,” he recalls.

Twelve border guards, 10 men and two women, gathered at the Hostomel border crossing point early that morning.

"Until then, nobody had said that something might happen. We didn’t have any weapons, and after the combat alarm was sounded, we still didn’t get any. So we just sat there and watched the news,” Sergei says.

The border guards waited for instructions about what to do next from their superiors. No orders came.

After six in the morning, a Russian rocket landed directly in the grounds of the national guard base: it hit the drill square just between a civilian dormitory and the tank crew barracks. The crater was massive – as deep as a person – but no one was injured in the blast.

"It’s anyone’s guess what they were aiming at... I think on old Soviet maps the dormitory was marked as the headquarters. And they wanted to take it out straight away," explains Ivan.

Around seven that morning, Volodymyr Zelensky’s address to the nation was shown on TV.

In a selfie video filmed on his phone, he said "Russia has struck at our military infrastructure and our border guards, our border guard units. Explosions can be heard in many cities of Ukraine. We are imposing martial law throughout the territory of our state."

Those watching in Hostomel were not to know that this would be the last time the Ukrainian president would address his compatriots in a suit and white shirt. Later that day, he changed into military fatigues.

After eight o'clock that morning, about three dozen special forces troops from the Main Intelligence Directorate of Ukraine’s defence ministry arrived at military unit 3018. The head of the directorate, Kirill Budanov, was the only representative of the Ukrainian authorities to have openly spoken about Russia’s preparation for a full-scale invasion before it started. He’d also said that an advance on Kyiv from the north would play an important role in Russia’s actions.

Naturally, military intelligence officers had visited Hostomel on reconnaissance before February 24th. So on the first day of the war, the special forces group (as yet nameless but subsequently to be known as the ‘Shaman Battalion’), had a general idea of the field of the forthcoming battle.

The group moved to Hostomel with a specific goal in mind. “We were told an attack was expected. We needed to make sure the airfield couldn’t be taken immediately so as to make time for the 72nd brigade [the army unit responsible for the defence of Kyiv] to bring up their artillery,” says Igor, one of the group members (name changed).

What he would find when he got there, Igor honestly didn’t know. “What should we do? We’d work it out when we got there. It’s a strategically important location.” Igor adds that at military intelligence meetings before February 24th, it was openly stated that Hostomel looked like one of the probable points for an assault by Russian airborne troops if war began.

Despite the anxious mood, employees of the Antonov factory, about 80 of them or a tenth of the airfield staff, had started to turn up. They held a meeting and decided first of all to move the ‘Mriya’ to a special hangar further from the runway to protect it. The aircraft was undergoing a technical service. Work was nearly complete: they were waiting for the delivery of a repaired engine, due to arrive on February 24th.

The Antonov workers also dispersed other planes around the airfield to prevent them being destroyed simultaneously. The task was complete by 11 am.

"Nothing much happened until about 10-11 o'clock... People’s mood was ok, nobody was hysterical. We tried to joke - black humour is a standard way of behaving in the army. The men were dealt out their equipment, and they set up weapons at their firing positions," recalls Andrey Kulish from the 4th National Guard Brigade.

And then the unexpected happened - everyone at Hostomel heard the roar of helicopter engines.

The landing of the paratroopers. "It felt like a terrible dream"

There were two National Guard positions on the airfield itself with about 20 men in total. They had ‘Igla’ MANPADs, anti-aircraft installations and small arms. The group Ruslan was in had a MANPAD and a few rockets for it.

Soldiers say that there were several tanks and APCs in special containers on the unit’s base. The tanks were out of order and stayed in their containers. The APCs were roadworthy and driven out to the forward positions. The rest of the unit’s equipment was in eastern Ukraine.

Ruslan and his mates continued to watch over the situation at the airfield.

“We were radioed that our aviation was in the skies, and we should be careful not to shoot anything down. Then we heard the deep rumble of helicopters. Our commanding officer was already at the position. He reported to his seniors that we could hear helicopters. “Whose?” they asked. “Well, we’re not sure.”

At that very moment, the Russian helicopters flew up one after another from beyond the horizon – attack Ka-52s and Mi-8 transport helicopters. It was immediately clear that there were lots of them – at least several dozen.

The lads knew these weren’t Ukrainian helicopters and quickly radioed the information in. “Well, that’s when it kicked off,” says Ruslan. The order was given to “fire to destroy”.

"The commander took the MANPAD. He tried to shoot down something, but the missile went wrong for some reason. It went off wrong, or he missed...”

The national guardsmen say their unit had old weapons. There were no western armaments. They had never fired the MANPADs before.

"I'm really an anti-aircraft gunner, not a MANPAD operator,” Ruslan recalls. “We had used simulators before, had trained for a week. It's exactly the same, just in virtual reality headsets. In real life, it's actually easier to shoot than with those headsets on." That day, he pulled the trigger on a MANPAD for the first time in his life.

On the other side of the runway, the second group of national guardsmen was already operating the anti-aircraft installation.

"We started shooting at them, and they shot back at us. As soon as our anti-aircraft gun began working them over, they immediately started firing at it," recalls one of the lads.

Ruslan, at his position, took the MANPAD in his hands: "I aimed, fired - and it hit him, it turns out. I fired, and then immediately started running for it, ran around the corner, because he started turning about - I thought he would start shooting at us. But he fell out of the sky somewhere around Blystavitse [a village five kilometres from Hostomel]."

Another helicopter, he says, was shot down by the anti-aircraft gun, but it managed to land.

After 11 am, when the fighting began, the unarmed border guards who were at Hostomel ran over to the bomb shelter. It was located in the airfield dining block.

"We could hear the sounds of explosions in the bomb shelter already. It was right at this moment that Hostomel was being attacked by airborne troops and the National Guard was fighting back,” says border officer Sergei. Workers from Antonov and a few national guardsmen also ran into the bomb shelter.

Another helicopter was downed by 25-year-old Sergei Falatyuk, who was a junior lieutenant at the time. “I saw the Ka-52, grabbed the rocket launcher and chucked it onto my shoulder. I opened the sights, pulled out the fuse trigger and primed it, aimed at the helicopter, saw it was really close to me, and then watched as it flew past me, turned round, and fired after it,” he said. The wreckage of that Ka-52 still lies on a dump at the airfield.

Attack helicopters were giving cover to the transport helicopters landing the airborne troops. “They constantly circled the base and the airport, right where our lads were. They flew in combat formation, firing their rockets and their 30-mm machine guns,” says Andrei Kulish

The national guardsmen kept changing their position when they saw the helicopters flying towards them. “They would fly out from one side of the building, and we ran round the other side. We were running round the building like in a cartoon,” recalls Ruslan.

The military intelligence troops helped out the national guardsman at the scene. Igor recalls that special forces soldiers also joined them aboard two armoured vehicles.

“We had one APC. The rest were pickup trucks, jeeps or our own personal cars,” Igor says. “Half of us were in civilian clothes. We threw on helmets and flak jackets and got on with it. When we got there, you couldn’t tell who was from which unit. It was just like: “’Is that one of ours?’ ‘Yes, one of ours.’ ‘What about that one – do we fuck him up?’ ‘Yep, fuck him up.’”

This was the moment when Hostomel really needed more anti-aircraft assets, he recalls. They ended up practically fighting the Russian paratroopers only on the ground, and couldn’t fire on targets in the air. “It was an overall problem. There was no other way, unfortunately. The situation we found ourselves in showed that we hadn’t prepared very well for a full-scale invasion.”

People who lived at Hostomel, and residents of neighbouring villages, came to watch what was happening at the airfield. They filmed the battle on their phones and instantly shared it on social media. Virtually the whole world was able to watch what was happening at Hostomel in real time.

While the battle in Hostomel was raging, journalist Simon Shuster describes in his book ‘The Showman’ how Volodymyr Zelensky and his closest associates, by that time already in a secret bunker in the centre of Kyiv, were glued to their phones and laptops, watching the events at the airfield more or less live.

"The president’s response caught some of his aides by surprise. They had never seen him in such a rage. “He gave the harshest possible orders,” recalled presidential advisor Mikhail Podolyak. “‘Show no mercy. Use all available weapons to wipe out every Russian thing that’s there.’" Shuster writes.

But after less than two hours of battle, the ammunition of the Ukrainians defending the airfield, unprepared for full-scale combat with an enemy that was far superior in terms of numbers and technology, ran out. Given the situation, the commanding officer gave the order to withdraw from the airfield. The departure of the national guardsmen was covered by the special forces soldiers. A few hours later, they too left.

A number of those defending Hostomel stayed at the airfield. Some hadn’t heard the order, others were in the bomb shelter. For now, everything at Hostomel was quiet for a while.

"We made up our minds to leave the bomb shelter. And here we were greeted by the Russians. They had already captured the airfield and were in control of it," says border guard Sergei.

The civilian employees of Antonov also stepped outside. "There were two entrances to the bomb shelter. We went out of one of them - and a Russian soldier with a St. George’s ribbon on his chest pointed his gun at us," recalls Vladimir Smus, the head of the air traffic control centre of Antonov.

Smus began to negotiate the evacuation of his personnel. "When we were talking to the Russians, they said, 'Don't be afraid, we've come to liberate you.' It was like a mantra to them."

"It felt like it was happening in a movie, a nightmare," he recalls. "There was no fear, nothing. It just felt like a terrible dream."

Following the negotiations, the Russians allowed all the civilians to leave the airfield. They let two women border guards leave with them. The remaining military personnel were ordered to go back into the bomb shelter. From then on, ten border guards and several dozen national guardsmen were prisoners of the Russians. Their phones were confiscated, so they didn’t know what was happening outside the bomb shelter. They were fed on Russian army dry rations, and some were occasionally led outside to load, move or stack the bodies of the Russian dead after Ukrainian shelling. Others stayed in the shelter throughout.

In the end, all the prisoners were driven by land to Belarus, and from there they were taken to detention centres on Russian territory.

The Ukrainian army strikes back

On the afternoon of February 24th, things got noisy again at Hostomel. The artillery of the 72nd Brigade, which had arrived in Kyiv from its base in Bela Tserkva to the south of the capital, was up and running.

Initial plans had called for the 72nd Brigade to conduct combat missions in Chernihiv region in the event of a full-scale invasion. The brigade officers had carried out reconnaissance there at the start of 2022.

But in early February, the brigade commander, Colonel Oleksandr Vdovichenko, was phoned by the head of the Ukrainian army, Valeriy Zaluzhny. “Others will fight for Chernihiv. Your job is Kyiv,” the general said.

"When I received the combat order, I said it was a very large front for one brigade, about 160 kilometres, and on both banks of the Dnipro river, too. On top of that, the brigade's units were manned at 50-60 percent - there weren’t enough men,” recalls Vdovichenko. “When I brought this up, the commander said ‘Alex, we just don’t have any more forces.’”

The situation, Vdovichenko continues, was saved thanks to the fact that experienced professional contract soldiers were serving in the ranks of the 72nd. "These are the elite of the armed forces," he says.

On February 23rd, the eve of the invasion, some of the brigades units were already on the outskirts of Kyiv, quietly getting ready to repel an attack. “The units were advancing, but didn’t take up defensive positions because we had been instructed not to reveal our presence near Kyiv,” Vdovichenko recalls.

About two in the morning of February 24th, the brigade commander told his chief of staff “They’ll probably make a move today. If only we had just another 24 hours to prepare.” A few hours later, Vdovichenko was awakened by explosions: the Russians had launched missiles at the airfield in Bela Tserkva and the army base not far from the town.

At this point, the brigade’s heaviest weapons – a tank battalion, artillery divisions and auxiliary units – were located at Bela Tserkva, which is nearly a hundred kilometres to the south of the capital. By the close of the day, all this equipment had reached Kyiv. Ordinary citizens helped get hold of trucks for the operation, and people even went on the local equivalent of eBay to buy trailers. Vdovichenko calls this military transport operation, heading in the opposition direction to the queues of civilian cars that were fleeing Kyiv, the ‘March of Life’.

The soldiers of the 72nd Brigade didn’t know yet that they would be working at the strategically important airfield at Hostomel. They thought other units would take care of it. However, Vdovichenko was in constant contact with General Olexandr Syrskyi, who led the defence of Kyiv, and was soon informed that the transport planes that would deliver the main invasion force were already in the air. They would soon be preparing to land at Hostomel.

So at around five in the afternoon, the 72nd Brigade’s artillery, commanded by Colonel Oleg Kobzarenko and occupying positions in the outskirts of Kyiv, open fire on the airfield’s runway.

The first task was to cause as much serious damage to the runway as possible to prevent Russia’s Ilyushin transport aircraft from landing. And the second was to ‘interdict activity’ by making it obvious to the Russians that if they went ahead and tried to land their planes they’d be shelled at.

It all happened in the nick of time. The investigative journalist Christo Grozev wrote on Twitter at 5.41 pm: "Ukrainian government sources tell me 18 Il-76 planes have left Pskov direction Kyiv, will arrive in about an hour.” [Pskov is the base of Russia’s 76th Guards Air Assault Division, considered one of the most combat-ready units of the Russian army.]

The 72nd Brigade carried out the task it was charged with. "If it weren't for this, the Ilyushin-76s would have landed. And the Russians would probably have been able to get to the outskirts of Kyiv," says Vdovichenko.

In parallel, Ukraine’s air force also attacked the runway at Hostomel on the first day of the fighting. For the next month, the 72nd Brigade maintained the defence of Kyiv, periodically shelling the airfield.

“The Russians still kept trying to land there [after February 24th]. But each time we got reports of planes in the air, we targeted the runway and worked it over. So eventually the enemy gave up on the airborne operation and organised overland logistics instead,” says Vdovichenko.

On the night of February 24-25th, Russian troops starting arriving at Hostomel from Belarus via the Chernobyl zone. They set up a command post at the airfield and created a kind of equipment and vehicle hub out of the runway and buildings in preparation for further action. The 72nd Brigade kept up intermittent shelling and the charred remains of Russian military equipment at Hostomel today are mostly the result of its work.

“One day they’ll write books about this operation of destruction,” says Vdovichenko.

The Myth of the "Heroes of Hostomel"

Even though the airfield defenders had to retreat at noon on the 24th, the battle for Hostomel is regarded as a victory in Ukraine. The Russian plan to build an air bridgehead into the suburbs of Kyiv, and then surround and capture the capital, had failed.

So it was with a certain amount of surprise that Ukrainians watched how from the very start Russian propaganda outlets put a halo over “the brave heroes” on their side who had supposedly achieved some kind of unique triumph.

The first the Russian public heard about the events at Hostomel was on February 25th, at a briefing on the ‘Special Military Operation’ by Russia’s defence ministry spokesman Major-General Igor Konashenkov. He reported that the day before, Russia’s military had carried out a successful airborne landing mission at Hostomel, on the edge of Kyiv.

In his account, more than 200 helicopters had participated in the operation. [Ukrainian sources cite different figures: eyewitnesses to the battle say they saw 35-40 aircraft, while Olexandr Syrskyi, the commander of the defence of Kyiv, speaks of around 80 helicopters.]

“During the capture of the airfield, more than 200 nationalists from the special forces of Ukraine were annihilated. There were no casualties among Russian armed forces,” Konashenkov said.

It was as though it were an unremarkable but victorious operation, and it was reported prodigiously by Russian propaganda during the first few days of the invasion. But on that very day, February 25th, a myth began to coalesce around the Hostomel paratroopers. An article appeared in ‘Zvezda’, the defence ministry publication, entitled “They call them ‘The 200 Russian Spartans’”.

The story was about two hundred ‘Russian lads whose job was to make sure transport planes could land at Hostomel, but found themselves surrounded by the Ukrainians all night and half the next day. They were forced into an uneven fight with a greatly bigger enemy force, “but they still held out, and did not abandon their positions,” the article read.

There was a hint in it that Konashenkov’s claim that there were “no losses” may not have corresponded to reality: “Sadly, they didn’t all survive to see the main Russian forces arrive by land. The airfield runway requires repair following several assaults. But they proved to the fullest that there are missions that no one except paratroopers can carry out.” Quite what the success of the operation consisted in, the article didn’t say: after all, the runway was never used.

It's hard to establish exact Russian casualty figures for Hostomel. What’s known is that during the storming of the airfield, its defenders downed at least three helicopters whose crews all perished. Two more aircraft crashed into the Kyiv Reservoir before reaching Hostomel. We don’t know exactly who shot them down. The people we have spoken to who took part in the defence of Hostomel estimate the number of Russians killed during the assault to be a minimum of 70. This number is confirmed by the former POWs at the airfield who were forced to carry away and stow the bodies of the dead in one of the buildings there.

The Year of the “Meatgrinder”. What we know about Russia’s war losses in 2023

As the Ukraine war approaches its third year, BBC Russian Service continues counting and profiling Russia's military losses.

Russian pro-war publications suggest the main role in storming and holding the airfield was played by special forces troops of the elite 45th Paratrooper Brigade, based in Kubinka outside Moscow (and considered for many reasons the very best in the Russian army) alongside men from the 31st Airborne Assault Brigade from Ulyanovsk.

By studying public obituaries, BBC Russian has established that in the first days of the assault on Hostomel, the 31st Brigade alone lost at least 34 men, including the battalion commander, Major Alexei Osokin. We also know that in three days of fighting, 13 special forces soldiers from Russian National Guard units were killed, including men from the elite ‘Vityaz’ detachment based in the Moscow region.

The retired FSB colonel who commanded pro-Russian separatists in Donetsk, Igor Girkin (also known as Strelkov) called the losses among Russian paratroopers at Hostomel “catastrophic”, though other military bloggers disagreed with him

Official figures from Kyiv state that at least two people died on the Ukrainian side during the battle: a State Emergency Service rescuer, and one of the Antonov employees. There were no casualties among the National Guard or intelligence officers who fought on the 24th. Approximately ten were taken captive.

At the end of March, another Moscow propagandist came out with a report on Russian forces at Hostomel. Alexander Kots writes for Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper and is one of Putin’s electoral trustees in the forthcoming Russian presidential ballot.

“The paratroopers at the airfield spent two days holding their positions amid utter hellfire. It was an operation without precedent,” he wrote. “We haven’t carried out tactical landings like this since 1943, when a detachment of 275 volunteer sailors under Major Cezar Kunikov landed on the fortified coast of Novorossiysk during the fascist occupation.” Two years later, Ukrainian marine drones would sink the huge Russian landing ship named in honour of Kunikov.

“Hostomel is our new place of power, a place of Russian military glory,” Kots asserted.

The main thing to emerge from Kots’s text is the first appearance of the phrase “Heroes of Hostomel.” It was immediately picked up by Russian propaganda: in an instant, it was all over posters and e-cards, and “Heroes of Hostomel” merchandise appeared for sale online.

There was even a song with the same name, written by a former policeman, now self-styled poet, Sergei Yefimov. It was performed by the once-popular Russian rock singer, Alexander Marshal.

The words of the song go:

“Shrapnel whips through the air like a lash,

There’s chaos on the airwaves, radio pandemonium.

Dying isn’t what’s truly scary:

What’s sad is to bite the dust for no reason.”

Two days after Kots published his article about the “Heroes of Hostomel,” Russian soldiers at the airfield got the order to retreat to Belarusian territory. You can still find mention of them, and photos on the topic, in the social media pages of war supporters. But it’s hard to say today what exactly it was these ‘Heroes’ actually achieved.

The destroyed "Mriya"

The fighting for Hostomel airfield continued into the last days of March. On April 2nd, the Ukrainian defence ministry announced that the territory of Kyiv region had been liberated.

“When we got back here after the de-occupation, there was a feeling of horror,” says Vladimir Smus of Antonov. “Buildings were obliterated, hangars destroyed, planes mangled. The whole territory was littered with shrapnel, the remains of ammunition, and burned out equipment. It was horrific.”

When they cleaned up the airfield grounds, Smus says, they counted up 150 items of destroyed Russian military transport and equipment.

Here, too, he first saw the devastated ‘Mriya”. One story says the largest plane in the world was fired on by the Russians. Another says it was the work of Ukrainian artillery targeting the airfield.

In Smus’s opinion, it’s more likely that the plane caught fire from burning Russian gear near the hangar after it had been hit by Ukrainian forces. The propagandist Kots said the same when he visited Hostomel while Russian troops were still there.

This version of events, explains Smus, is supported by the fact that the nose section of the aircraft, which was closer to the Russian equipment, was completely burned out, while the rear remained intact. In the end, about a third of the equipment of the ‘Mriya’ turned out to be suitable for use in other aircraft.

"Some engines are completely destroyed, while some have already been restored and are used on An-124 aircraft - they are identical," says Smus.

We have seen a Ukrainian SBU secret service investigation which states that an unguided rocket used by Ka-52 helicopters was found in the stern of the ‘Mriya’, meaning Russian aircraft also fired on it. Along with the ‘Mriya’, the battle at Hostomel destroyed two other planes completely – an An-26 and An-74 – while five more were seriously damaged.

It’s not clear what will happen next with the airfield itself. A museum is planned there in the future for the remains of the ‘Mriya’. But using the airfield for its intended purpose is a bigger challenge. All the equipment was destroyed in the fighting. The Antonov concern estimates it will take $32 million to restore aeronavigation apparatus alone at Hostomel, not to mention the cost of resurfacing the runway and rebuilding the infrastructure.

In addition, a large part of the airfield is still mined, while civilian flights over Ukraine won’t happen until the end of the war. There are sufficient reasons why western donors aren’t falling over themselves to help repair Hostomel.

A year on from these events, in the spring of 2023, the SBU began to look into the preparedness of the airfield before the invasion, and the destruction of the aeroplanes. The investigation found that the management of Antonov did nothing to evacuate the fleet, despite warnings of a possible Russian offensive. Moreover, they prevented national guardsmen from building defences at the strategically important airfield.

We spoke to an Antonov employee on condition of anonymity. He says that after the invasion started, the management of the aviation giant distanced themselves from things: on February 24th, they simply sent the workforce home. The situation at another Antonov aerodrome, at Svyatoshino on Kyiv’s western outskirts, was indicative.

As the invasion began, when chaos and panic reigned in the Ukrainian capital, three members of the armed security staff, a few aviation security personnel, and three company security officers showed up – all of them without weapons. This small group of men were supposed to protect 173 hectares of grounds, including the runway and helipad. It was several days before armed SBU fighters arrived at the facility; and even later, national guardsmen and armed forces personnel.

As a result, three of Antonov’s directors were charged: former director Sergei Bychkov, his deputy Mikhail Kharchenko, and aviation security chief Alexander Netesov. The first two were arrested immediately and the third has been declared wanted.

Questions without answers

Talk about the guilt or otherwise of the former Antonov directors, however, fades against the background of the multiple questions that remain two years after the battle for Hostomel began.

The first is a global one, concerning Ukraine’s preparation for war in general. Literally one week before the invasion, in an interview with RBC-Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelenksky said: "We can increase the army two to three times, but then, for example, we won't be able to build any roads."

As a consequence, the very first days of the war demonstrated one of the key problems in defending Kyiv: a lack of troops to fight back against the Russian forces, which significantly outnumbered those defending the capital.

Sources we have spoken to recall that in the winter of 2022, even in the final days before the invasion, the most probable scenario was thought to be a Russian offensive in the Donbas alone – the more so when Russia recognised the independence of the self-proclaimed ‘People’s Republics’ within the entirety of the regions’ borders on February 21st. A direct attack on Kyiv seemed like fantasy.

So it’s an open question whether it would have been worth halting the scheduled rotation of the 4th National Guard Brigade, supposed to be in charge of defending Hostomel, the most combat-ready members of which had departed to the east on the very eve of the invasion.

On one hand, it left the defence of the airfield to conscripts, and to the fighters from other units who hurried to their aid early on February 24th. Yes, everything worked out well for them in the end. But had the defenders of the airfield been less fortunate, and Hostomel had started to receive Russian transport planes, Kyiv’s fate would have hung by a thread.

The journalist Simon Shuster writes in his book ‘The Showman’ that once the immediate threat to Kyiv had passed, the US Joint Chiefs of Staff chairman, Mark Milley, talked through the battle for Hostomel, and Russia’s failure to quickly capture the capital, with Ukraine’s armed forces commander-in-chief, Valeriy Zaluzhny.

“When they discussed the battle for Hostomel, and the broader Russian failure to take Kyiv in less than a week, Milley did not ascribe the success to clever Ukrainian planning,” Shuster writes. “It looked more like a military miracle. “He told me: ‘Son, you just got lucky,’” Zaluzhny said. The comment stung.”

We wrote to the National Guard command to request more information about the decision to rotate the 4th Brigade, but were told troop redeployment information is classified.

On the other hand, there are voices in support of the decision to rotate the troops.

“To conduct successful operations against dozens of Russian battalion tactical groups entering Kyiv region – I don’t think there’s any brigade with enough men to counter that,” says Andrei Kulish, the 4th Brigade press officer.

"Also, the defensive line of Kyiv ran along the River Irpin. Hostomel airfield is located on the other side of it, four to five kilometres away. Holding it to the bitter end would have just provided Ukraine with a couple of thousand posthumous heroes," he says.

The national guardsmen redeployed to the east were engaged in heavy fighting by the morning of February 24th near Stantisa Luhanksa, and forced to retreat, before holding back the Russian advance through Luhansk region for a substantial period. If not for them, it’s possible that the situation on the eastern front in the first days and weeks of the war may have become much worse for Ukraine. Then again, given the huge force the Russians massed against Kyiv, the presence of such fighters with significant combat experience might have meaningfully bolstered the defence of the capital.

Another question: why when western intelligence was warning of a possible airborne assault on Hostomel did the authorities not fortify it with additional experienced units? And why were strategic military-industrial enterprises like Antonov told to keep on “as usual” because there was “no reason to panic”? Why weren’t the aircraft, including the unique ‘Mriya’, evacuated overseas?

One more frequently asked question: why did Ukraine’s air defence forces permit dozens of Russian helicopters to fly around 100 kilometres into Ukrainian territory from the border and reach Hostomel? Our sources in the armed forces general staff say the air defences were functioning and several helicopters were shot down on the approach to Hostomel. Most likely, the two Russian helicopters that were dredged up from the bottom of the Kyiv Reservoir were evidence of this.

Yet a whole swarm of helicopters still made it to their target. The explanation from our general staff sources is that Ukraine’s air defence systems at the time were very feeble, that soldiers had virtually no western arms at their disposal, and that the old kit they were using sometimes didn’t even work.

Last, there’s the question of how well-defended Kyiv would be in the event of a new Russian attempt to attack the city. Those we have spoken to have a laconic response: the lessons of 2022 have been learned.

The BBC’s Ukrainian service interviewed the former Ukrainian armed forces commander-in-chief, Viktor Muzhenko. Analysing how it was that despite the Russians’ detailed plan to capture Kyiv within a few days, they failed to reach the capital, Muzhenko said “We were helped out by God, and the heroism of the Ukrainian army.”

After the retreat from Hostomel, National Guard soldier Ruslan was initially transferred to Zhuliany, another airfield on the southwestern outskirts of Kyiv, before returning to the military base at Hostomel in April. It has been completely renovated, he says, and conditions there are even better than they were before the invasion.

The professional contract soldier Ivan is still serving in military unit 3018 near Hostomel airfield.

Oleksandr Vdovichenko, the commander of the 72nd Brigade, continued to fight on after the battles for Kyiv, first in Sumy and Kharkiv, and then around Bahmut. He resigned as brigade commander in August 2022 and is currently studying at Ukraine’s National Defence University.

Special forces soldier Igor continues to serve in the Main Intelligence Directorate of the army.

Sergei, the border guard, did time in a Russian prison, along with the other POWs taken at Hostomel, until mid-April 2022. They were let home gradually, with the last of them released in an exchange in February 2023. When we spoke with him, Sergei was reluctant to dwell on the time he spent in captivity. He dryly mentioned that he and the other Ukrainians had been subject to torture and abuse. He and the other men were treated in hospital on their release and are now back serving in their units.

During their time in the Russian jail, the prisoners had no idea about what was happening in Ukraine - in Bucha, Irpin, and Hostomel. They had no contact with their families. Returning home was a shock.

This story was produced jointly by BBC Russian and BBC Ukraine.

With additional reporting by Dmitry Vlasov, Ilya Barabanov and Olga Ivshina.

Collages by Angelina Korba.

Read this story in Russian here.

English version edited by Chris Booth.