Ukraine War: Is Putin’s toxic masculinity really to blame?

Patriarchy and machismo remain dominant in the wider Russian power establishment and play a role in popular support for the invasion.

By Elizaveta Podshivalova

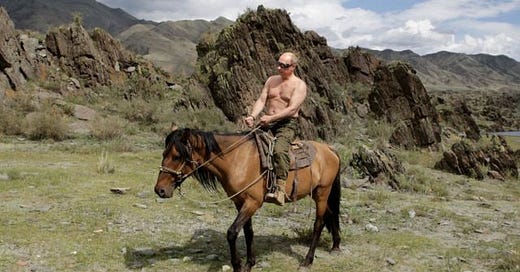

Topless on horseback was Vladimir Putin’s most memorable image. Photo © AFP

When Boris Johnson, then UK’s prime-minister, suggested that had president Putin been a woman, he would not have started a war in Ukraine, this caused a storm of indignation in Russia. Not surprising, given the Russian president’s long and careful honing of his image as a ‘real man’. Several analysts told BBC News Russian that patriarchy and machismo remain dominant in the wider Russian power establishment and play a role in popular support for the invasion.

“If Putin was a woman, which he obviously isn’t, but if he were, I really don’t think he would’ve embarked on a crazy, macho war of invasion and violence in the way that he has,” Boris Johnson said in June.

“If you want a perfect example of toxic masculinity, it’s what he’s doing in Ukraine.”

Johnson’s words were later echoed by the UK’s defence secretary Ben Wallace, who said that Putin had “small man syndrome” and that his “macho” view of the world had caused the war.

Following this, the Russian Foreign Ministry summoned the UK ambassador to Moscow to berate her for “the frankly boorish statements of the British leadership”. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov suggested Johnson makes an appointment with the founder of psychoanalysis, Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856-1939). President Vladimir Putin himself gave a short lecture on the “cruelty” of Margaret Thatcher, UK’s PM in the 1980s.

Did Boris Johnson hit a nerve to cause the Russian officials to hit back so harshly?

A ‘real man’ and his effeminate foes

Throughout his presidency, Vladimir Putin has consistently signalled to the world his physical strength and bravery. He descended to the depths of a Siberian Lake Baikal, paraglided with a flock of cranes, dived for ancient Greek amphorae near the coast of Crimea, protected the endangered Amur tigers in the Russian Far East and, most memorably, posed topless on horseback.

The image of ‘macho Putin’, a defender of ‘traditional’ values and a ‘strong leader’ has long been the butt of jokes in the West. Even at their latest summit, G7 leaders indulged in ironic comments, with Johnson mockingly suggesting participants should remove their jackets to prove they were “tougher than Putin.”

The qualities Putin has tried hard to display have a whiff of what is commonly referred to as ‘toxic masculinity’, often defined by toughness, seeking power, emotional distance, homophobia and contempt towards women.

Professor Elizabeth Wood, a historian and specialist in gender research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the United States, says the Russian president routinely feminises his enemies and, in this way, lowers their status.

“Before the war, the Russian authorities constantly accused the West of ‘hysteria’. It’s clear that the word ‘hysterical’ is derogatory, and is usually addressed towards women,” she says.

Putin responded to the jokes at the G7 summit by saying that it would be a “disgusting spectacle” if Western leaders were to remove their tops and advised them to take up sport.

The Russian president’s close associates use a similar strategy to insult their opponents.

In mid-March, the maverick Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov mocked billionaire Elon Musk by twisting his first name into a feminine variant, ‘Elona’.

Kadyrov invited the businessman to take up fitness training at the Chechen bootcamp ‘Akhmat’, where he would be transformed from “a gentle girl into a brutal man.” Musk seemed amused by the suggestion, and for a period even changed his Twitter handle to ‘Elona Musk’.

State building and ‘a new Russian masculinity’

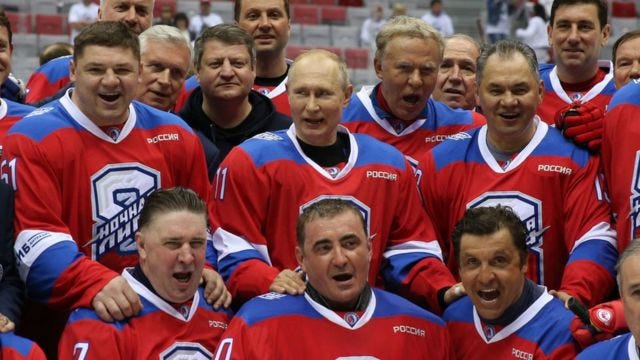

One example of an influential and exclusively male organisation is the Night Hockey League, in which Putin plays alongside civil servants and professional athletes. © Getty Images

And it doesn’t stop with Putin, or Kadyrov. Many experts point out that Russia’s entire power structure is built around the idea of masculinity.

Even as Putin was beginning his transformation into ‘a new type of Russian manhood’, Russia’s image underwent a change, too, says Elena Gapova, Professor of sociology at the University of Western Michigan.

"[The new type of man] was no longer some bespectacled intellectual from a 1980s Soviet romcom, lost in thought travelling on a suburban Moscow train. Instead, he embodied a cold, strong-willed ideal – a representative of a new class of result-oriented managers,” she explains.

In the early 20th century, philosopher Vladimir Rozanov defined Russia as “a woman forever looking for a fiancé”. In the early 21st, a pop song ‘Someone like Putin’ topped the charts - it describes a woman, also looking for a fiancé. Except in her case, she knows that she wants this fiancé to be a spitting image of the Russian president.

“Russia wanted to see itself like Putin,” Professor Gapova explains. “A metaphor emerged of ‘Russia getting up from its knees’, and a masculine ideal appeared, which was embodied by Putin and his cohort. At the same time, in the 2010s, a process of state building was underway that was focussed on a strong centralised power. The connection between this project to establish a strong state and normative masculinity seems clear.”

Always the alpha male

But even in an exclusively male environment, Putin seems to need to remain the alpha male. According to Professor Elizabeth Wood, this assertion of masculinity has become Putin’s way of demonstrating his own power.

“On the one hand, he projects the image of a rational, practical individual – he is to the point and capable of solving technical questions,” she observes. “On the other hand, though, he shows constant aggression.”

Wood recalls a famous incident in 2009 when Putin visited the town of Pikalyovo, in which local residents were protesting the shutdown of enterprises: “Putin flew in by helicopter and chastised everyone! He chastised the workers and the managers, but he especially chastised [businessman Oleg] Deripaska.”

The expert draws a parallel between this incident 13 years ago and a much more recent one - in February this year. In the latter, during a National Security Council meeting days before the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Putin famously berated the chief of Foreign Intelligence Service Sergey Naryshkin. Naryshkin, an intelligence officer with decades of experience, is considered to belong to the Russian president's inner circle.

“He aggressively demanded an answer – yes or no. That’s how he demonstrated that he’s still ‘alpha’ in all situations. These ‘shake-downs’ are also a very masculine trait.”

But still, what if Putin were a woman?

Even in an exclusively male environment, Putin seems to need to remain the alpha male. © Getty Images

All the experts we spoke to agree on one thing: Johnson’s suggestion that a female version of Putin would not have started the war is linked to stereotypes.

“Johnson’s words should be taken more as a metaphor,” says Elena Gapova. “There’s a traditional perception that women are less aggressive and more empathetic than men, but this is due to the fact that women are less likely to occupy those social positions from which you can start a war or make major decisions.”

According to Gapova, any speculation that the wars and revolutions of world history can be attributed to the patriarchy, and that history would have been different had more women been in power, are rather esoteric.

It’s true that Johnson refers to stereotypical ideas about women which say it’s easier for women to negotiate or show weakness or emotion, but he uses them to counter Putin’s stereotypical masculinity, says psychologist Marina Travkova.

“For women there’s no (or at least, less) shame in ‘backtracking’ or ‘apologising’,” she explains. “Moreover, masculinity is linked to heroism – with the idea of dying for the state, rather than living with one’s children and being a hands-on father. Women, meanwhile, are more involved with their children. They’re less likely to support that kind of heroism, and in that respect, I think Boris Johnson’s comment is valid.”

Read this story in Russian here.

Translator Camilla Yermekbayeva.