‘It’s like a trap’: How the Russian army holds onto disillusioned contract soldiers

They dream of serving their country but have to face mismanagement, violence, extortion and no easy ways to quit.

By Olga Ivshina and Olga Prosvirova

Many new soldiers will be heading for the war since the announcement of mobilisation. Most never planned to tie their lives to the army, and have a poor understanding of it works. However, amongst the contract soldiers already fighting and those who have quit, there are a significant number who ‘dreamed of a heroic officer’s future,’ and found that once they had got themselves into the Russian army, getting out was not so easy.

He just didn’t have the money

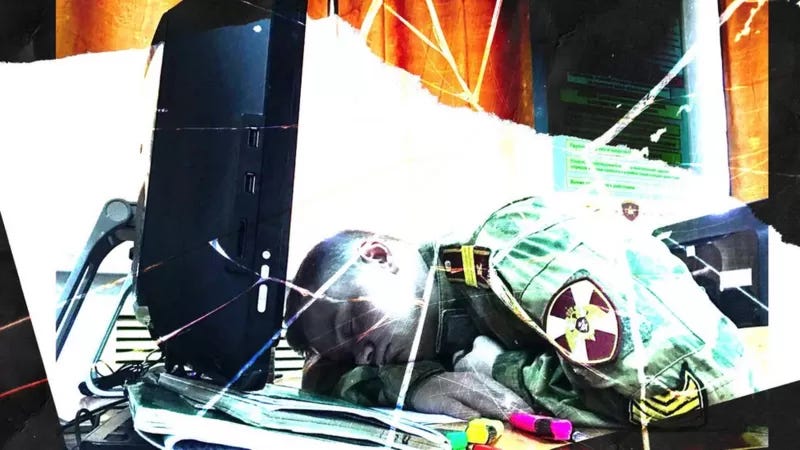

In May, several weeks before he was sent to war, special forces officer Nikita Tsvirenko wrote to his friends, asking them to lend him money. He explained that he needed to buy a uniform and equipment.

“What do you mean? Don’t they provide you with uniforms? You mean – you go into the special forces, you carry out operations, and they expect you to buy your own stuff?” Maxim, Nikita’s friend, was surprised. (Maxim’s name has been changed at his request.)

“I want to live,” Tsvirenko told his friends, “And it’s practically impossible to survive with what you’re given.” He promised to return the loan in September, as soon as he got back from the war.

Nikita Tsvirenko was born and raised in Novosibirsk. His family never had much money – his father was a construction worker, his mother was a teacher. Nikita did well at school. He went on to university, where he studied global economics. He was a straight-A student for his first two terms, and then – to the surprise of his friends – dropped out of university and went into a military institute.

His sister, Anastasia, explains: “Nikita didn’t want to be ‘just an office worker,’ and decided to follow in the footsteps of our granddad and uncle, who served in the Soviet army.” But one of Nikita’s friends doesn’t believe this version of the story.

“Nikita was never a fan of the military system. But he had to make a living somehow. He wasn’t getting any money from his parents – quite the opposite, he wanted to help his mother and sisters. In this way, military school seemed like the solution to the problem. Civilian life is unstable, especially when you’re young. At the school they fed him and gave him a uniform, they even put him on benefits of some sort,” says Maxim.

In the words of one of Tsvirenko’s other friends, Nikita already knew after a year of studies that the army or the National Guard wasn’t his dream career. But having joined up, he found himself in a vicious circle.

“After his first year, Nikita was already saying that he had no illusions about the military school, or about his career,” his friend recalls. “He said that he’d almost certainly taken the wrong path - the reason he stayed was definitely a financial one. If you drop out of a military school, you have to reimburse the state for the cost of your training. It’s a huge sum of money – and he just didn’t have it.”

As stated in the law on military service, it’s true that military drop-outs have to pay back the budget funds spent on their training. Depending on their specialty, this is an average of 150,000 to 200,000 roubles a year, sometimes as much as 400,000.

That’s a lot of money in Novosibirsk. The median salary – a more accurate figure than the average – is just under 28,000 roubles a year. This would be typical for a school-teacher, for example.

To avoid payments, it’s not enough just to graduate from military school. Cadets have to sign a contract with the Ministry of Defence or the National Guard, and complete a minimum of five years’ service.

According to his sister, Anastasia, Nikita never complained about the school or the service in his conversations with family, and if he had really wanted to drop out, they would have definitely supported him.

"He didn’t have the decisiveness"

After leaving the military institute, Nikita Tsvirenko was assigned to ‘Mercury,’ a special forces unit of the National Guard in Smolensk. This is considered an elite unit.

In the Smolensk special forces, a young officer was promised a 90,000 rouble monthly salary, giving Nikita hope that he’d be able to provide for himself and help his sister. However, two months after his transfer, he still hadn’t been paid – claim two of Nikita’s friends, from whom he was borrowing money at the time. “He was barely making ends meet,” says one friend. Tsvirenko didn’t complain to his family about his financial problems.

“Nikita was always kind, even a little naïve,” his friend believes. “He wanted to help people. One time, we were on a bus and a woman passed out. Nikita was one of the first to help her. He was a simple guy, completely like a civilian. The military have this particular manner of communication, their own way of thinking. Nikita was nothing like that.”

“His training sometimes brought him to Moscow, and after work we go for a stroll, go to various trendy cafés. He was like a kid, everything made him happy. Even the low-floor tram impressed him. It seemed like he loved peaceful life. He used to ask me about ways for people to earn a living outside the army. He said he wanted to leave the National Guard as soon as his first contract ended. But I was afraid that it would be hard for him to settle down and find a civilian job,” says Maxim, who has now left Russia.

After February 24th (the day Russia invaded Ukraine) ‘Mercury,’ like the other divisions of the National Guard, was deployed to the frontline.

Judging by multiple testimonies from soldiers, the Russian forces invading Ukraine were given first-aid kits with bandages and tourniquets from the 1960s. The commandos had no night-vision equipment or thermal imagers. A few days into the invasion, several Russian army veterans – now popular bloggers – wrote posts asking their followers to donate money towards the needs of military personnel. Nikita Tsvirenko was in the second wave of soldiers sent to Ukraine. He was deployed to the Donetsk region in June, and a month and a half later his base came under rocket fire. 25-year old Tsvirenko was killed on the spot.

“He was a thoughtful guy,” says another of his friends. “He saw and understood the whole shitshow, all the irregularities that went on in the National Guard. But he didn’t have the courage…the decisiveness to take the leap to a peaceful life, and finish the story. I understand that it’s difficult. But in the end, he died before he was really able to live.”

“It was a great honour”

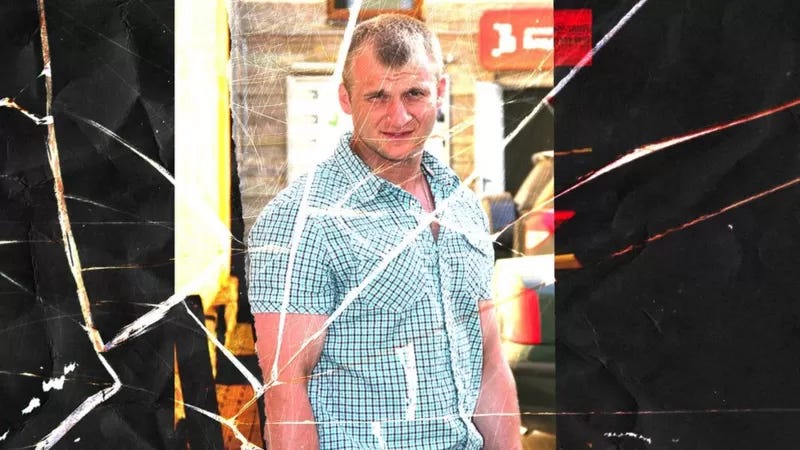

Unlike Nikita Tsvirenko, 38-year old retired captain Sergei Lintsov had dreamed of a ‘heroic officer’s future’ since childhood.

“My father was a soldier, he died from the last wound he got in Afghanistan. He spent ten years living in agony, deaf and crippled from the explosion. And it was always presented to us as a great honour. Mum always admired the army, and admires it to this day. I wanted to be like my dad. You see, in Soviet society – and then in Russian society – soldiers were always highly valued, placed on the same pedestal as astronauts and doctors,” explains Sergei.

Sergei’s father said little about the war. He only said that he’d been very afraid of being captured, and always carried a grenade on him.

To get into military school, Sergei Lintsov travelled 2,500 kilometres from Kursk to Tyumen. He dreamed of becoming a sapper like his father, and all the best combat sappers trained at the Tyumen military academy. Sergei’s studies hinted at what life was really like in the Russian army, but he hoped things would be different once he was in the army itself. Lintsov longed to be sent to Chechnya where he was “sure that Russians were wrestling with evil."

He wasn’t sent to Chechnya. He ended up in the Leningrad region instead, part of the guard’s brigade of constant combat readiness. His fascination with military service quickly turned into shock.

Lintsov recalls that the senior officers were permanently drunk, and communicated mainly in swear-words. He remembers cases of outright bullying of conscripts by commanders. He claims to have witnessed a young conscript being forced to lick the mud off an officer’s boots. “We all kept an eye out for that guy, in case he decided to kill himself.”

He explains that he wasn’t prepared for the drills, during which eight out of ten vehicles returned to the base broken – the equipment was faulty or too old, the soldiers’ uniforms were one-to-two sizes too big, and most of the officers treated their charges with indifference.

“There was a gang in our unit who stole salaries from the youngsters. Everyone knew about them, but most of the so-called officers pretended that nothing was happening. I tried to get involved, but they started to threaten me, they swore they’d kill my wife and baby son. How surprising that just a couple of hours before I received the threatening phone call, a colleague appeared in front of me and said “Be careful, they might go after your family.”

Russian journalists have often reported on how soldiers experience extortion in the army. There was a recent, high-profile case of racketeering in the artillery brigade in Yugra. Several cases even reached the courts. For instance, in 2019, three contract soldiers received suspended sentences for extorting from fellow soldiers in annexed Crimea. In 2020, the Ministry of Defence reported that hazing and ‘barracks hooliganism’ had been completely eradicated. Nonetheless, according to data from human rights activists and journalists, gangs continued to extort money from military personnel in parts of the Altai, Primorsky and Trans-Baikal territories, and in Khanty-Mansiysk and Chelyabinsk.

For the sake of a pension and an apartment

Sergei Lintsov say that there are only a few ‘real’ officers, in his understanding. “The rest served only to get an early pension, an apartment, benefits, and be praised for 'the years of service to the Motherland'."

Many contract soldiers receive their pensions 20 years earlier than civilians. For officers, the wait is even shorter – years spent in training are counted as ‘years in service.’ And if a soldier served in dangerous conditions, service days are multiplied by one-and-a-half, or doubled. Veterans receive all kinds of discounts, particularly on medicine and in public transport.

The army traps many soldiers via the ‘military mortgage’ – a contractor can get an apartment through a special scheme. Whilst serving, the soldier has his mortgage paid by the Ministry of Defence. If a soldier serves twenty years, then the state repays the mortgage in full. But if he leaves without a valid reason, all the money has to be returned.

Sergei Lintsov served for six years. Ultimately, he grew disillusioned and decided to quit the army. This turned out to be quite complicated. “For a long time they tried to mess with my head, tried to scare me, they put spanners in the works, they summoned me for various little chats. But I’d already made my decision. Formally, I left on grounds of health, I had an ulcer. They didn’t believe me. When I had my gastroscopy there was even a counterespionage officer standing beside the doctors.”

There are very few grounds for dismissing a serviceman before his contract ends. The main reasons are deterioration of health (the medical commission must confirm this), reaching the age-limit for service, or a court intervention. During mobilisation these terms still stand. But there are already known cases where people with serious health problems have been mobilised. A medical commission should have declared them unfit for service, but families of conscripts said that the recruitment office had refused requests to be seen by doctors.

All the same, Sergei left the army in 2013. His mother is still disappointed that he didn’t complete his service. “She supports the ‘special operation,’ so we don’t communicate much these days.”

It wasn’t easy to find work as a civilian. At one point, Sergei worked in a cancer clinic, and then taught for a bit. At present he isn’t working.

Before the outbreak of Russia’s war in Ukraine he kept in touch with fellow servicemen. “When you create a lot of fake news and openly lie, you start believing your own words. And that's how the country's leadership believed in the capability of their army. But from my conversations with ex-colleagues throughout the years, I’ve realised that nothing has changed in the army to this day."

It’s harder to quit than to settle

“Ten percent of soldiers believe the stories that Ukraine has to be delivered from fascists. All the rest – and I include myself here – we were there, realising that it was all bullshit. And yet we stayed, because…” former paratrooper Pavel Filatyev searches for an explanation and falls silent, lowering his eyes.

On February 24th, as part of the 56th air-assault brigade, he invaded Ukrainian territory. According to Filatyev, he realised that this was an attack against Ukraine – and not a response to an attack on Russia – after just one week of fighting.

Filatyev first experienced the Russian army when he was drafted, before signing a contract and serving for three years. He quit in 2010 and worked on a stud farm for a long time.

As he wrote in his book ‘ZOV’ (the tittle is reference to Latin letters Z and V used by the Russian army to identify its forces, the word translates from Russian as 'Call'), work and money at the farm dried up at the beginning of the pandemic. “It was a narrow field, and wages were falling. At the beginning of 2021, I decided to return to the army. I was getting on a bit, 33 years old and I still couldn’t afford my own home.”

He saw the Russian army in much the same way as Sergei Lintsov. In his memoir, Pavel Filatyev describes how he couldn’t get a uniform in his size within ten days of arriving at his unit, and ended up buying his own beret and pea-jacket. Instead of receiving combat training, paratroopers were sent to mow the grass around the unit’s fleet of vehicles.

Filatyev tried to defend his rights, but earned only reprimands, extra duties, and abuse from his superiors.

“The majority [of people in the army] have a thirst for order and are very in favour of reform: they want to get their military training rather than to pretend being busy. But they learn - from cases like mine - that attempts to achieve something only lead to trouble with their superiors, and they decide that the price is too high. It is even harder to quit the army than it is to settle into it,” Filatyev believes.

BBC Russian Service spoke to five other young Russian officers who tried to leave the Russian army over the last three years, even before the war in Ukraine. All five confirmed that when they informed the command of their decision to quit, they were met with threats and attempts to stall. For example, their statements and important documents were lost, they were sent on wild goose chases between various authorities, they found themselves facing criminal charges and problems with their subsequent employment.

Many soldiers are well aware that the picture of the army that once existed in their heads bears no relation to reality.

"We grew up in a Russian society where the TV churns out patriotism from dawn till dusk, we learned that it’s an honour to die for the good of the motherland. We learned that a man shouldn’t be a coward, he has to be a warrior. They relentlessly showed us all these war films,” Filatyev explains. “You go into the army at 18 or 19, still pretty young and clueless. And then they just brainwash you from morning till night, they’re like: “Oh, you’re a man, you can’t complain, put up with it.”

“As a result of those attitudes and stereotypes beaten into us, we find ourselves at war and we don’t know what to do, even though 90 percent of the guys know that it’s all rubbish, and that we’re just pawns in someone’s political game. For a long time I was glad and proud that I became a soldier, a paratrooper. But since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, and as it develops, I regret it – of course I do.”

Pavel Filatyev spent two months on the frontline, only returning to Russia after an eye injury. When he got back, he wrote his book “ZOV,” and publicly condemned the actions of the Russian army in Ukraine. Filatyev then fled the country and claimed political asylum in France.

“By 2012, the repressive regime in Russia was just starting to pick up speed. And now all the punitive measures have been carefully honed. People are detained on the basis of conversations, or posts on social media. It seems to me that many are already afraid to speak openly to each other, for fear of being denounced. The gulag is back, and it’s getting scarier every day. We have the strength to die at the front for ideals we don’t believe in. But we lack the strength to say no to war.”

BBC Russian Service sent a request to the Russian Ministry of Defence for a statement on its heroes’ stories about the state of the Russian army, but has yet to receive a response.

You can read this story in Russian here.

Translated by Pippa Crawford