The life and death of "a big child"

Andrei Kotov was arrested for ‘LGBT extremism' and took his own life in a Russian detention centre.

By Nina Nazarova, Anastasia Platonova.

Andrei Kotov was 48 years old at the end of last year, when he took his own life at a pre-trial detention centre in Moscow.

Kotov had been arrested on charges of founding an extremist group engaged in ‘gay tourism’. He was subsequently accused of making child pornography.

Russia’s Supreme court declared the so-called ‘international LGBT movement’ an extremist organisation in November 2023, and banned it. Six cases concerned with ‘LGBT extremism’ had been opened in Russia before Kotov’s became the seventh, and most highly publicised.

At his detention hearing, Kotov testified that he had been beaten and tortured with electric shocks. Russia’s financial monitoring body added him to a list of terrorists and extremists, and pro-government media and Telegram channels mocked him as a ‘pervert’.

A month after his arrest, in the early hours of December 29th, Kotov killed himself.

His friends and family speak of him as an inventor, a videographer, and as a “big child” who was “not of this world.”

The BBC has found that many of the so-called ‘gay tours’Kotov was said to have organised didn’t even take place.

This is his story.

“His fish didn’t die”

On the ninth day after the death of Andrei Kotov, six people gathered to remember him at a friend’s house.

One of them, an entrepreneur called Konstantin who preferred not to give his surname for safety reasons, recalls that the Queen song Bohemian Rhapsody was played at some point. “It was the perfect coincidence. He was exactly like Freddie Mercury – a carbon copy. Very artistic yet a big child.”

Kotov was a Buddhist and vegetarian, but had been working out in the gym since he was 12. He weighed 140 kilos. “I once asked why he trained so hard, because he was just this vast wall of muscle,” Konstantin recalls.

“He told me had been badly hurt as a child and had sworn never to let it happen to him again.” Another friend, Svetlana, compared him to a huge, kind panda bear.

Kotov was born in Ivanovo, not far from the Russian capital, and finished both high school and the local institute of chemical technology with honours. His mother, Larisa Kotova, had worked in the tourism industry since Soviet times. She would often take her elder son and young Andreialong with her on trips from the Baltic states to Central Asia.

She remembers that her son had an eye for entrepreneurship and a love of animals from an early age. As a schoolboy, Andrei asked her for $350 to fund a business idea. He travelled to Moscow and came home with a pedigree Great Dane, intent on breeding puppies.

“‘What’s this?’ I asked. ‘Mum, you won’t even see him!’ Andrei said. Then he’d be late for school in the mornings, saying, ‘Mum, take him for a walk.’ Well, I ended up being the one walking that dog for the next ten years,” Larisa Kotova recalls.

Andrei graduated from university at the time of the ruble crash in 1998. Eventually he took a job in a bank, but didn’t like it. He started designing custom aquariums instead.

“His fish didn’t die. Everyone else’s did, but his didn’t,” his mother explains.

Kotov’s friend Konstantin says he was fanatical about his new passion, obsessed with the quality of life of the fish swimming in his structures. Konstantin introduced him to the Skolkovo innovation hub. Dmitri Medvedev had launched it as an answer to Silicon Valley during his interregnum as Russian president.

Kotov started a company specialising in smart fish farming, favouring automation and remote control over the heavily hands-on approach that was current. The idea was taken seriously – the head of Russia’s fisheries agency was convinced, and even the government minister was paying attention. It looked like Kotov’s project was about to be implemented across Russia. He was thrilled.

But it didn’t pan out, Konstantin says. Instant returns were called for but the seed capital wasn’t provided. Russia lacks venture capital markets to move promising projects to scale and profitability. “I think that really broke him because you should have seen how high his hopes were. He truly believed in this whole story."

Further grant funding was denied after the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, his mother says. But Kotov kept coming to Konstantin for advice. "I tried to keep his feet on the ground and think critically. But he just didn’t know how. He couldn’t do it. In that sense, he really was a big kid."

Larisa Kotova echoes the sentiment: "My son was naïve; like a three-year-old child with a brilliant mind."

"Not for profit, but out of desperation"

Those close to Kotov describe him as bright and well read. His mother says that he often pestered her to read Nobel prize winners instead of wasting her time on "internet junk."

"He got frustrated when people around him didn’t meet his intellectual level,” Konstantin says. “He had three higher education degrees, he was talented, and he knew he was talented. Sometimes, it would irritate him: ‘Why don’t they understand? Why doesn’t the world love me?’

"Again, it reminds me of Freddie Mercury in the movie. He was very lonely, and he suffered a lot. I’m not part of the LGBT community and don’t know much about that aspect of his life, but I do know that he was lonely. He had very fewfriends. In part, perhaps, because of that very same extraordinary naivety.”

As well as his first degree in economics, Kotov qualified as a psychotherapist, though he apparently never practised the profession, and also gained a qualification in videography. At the time of his arrest, he could be found on a freelance gig website, available for birthdays, weddings and corporate events. His social media page was devoted to photography and video.

When his mother Larisa asked how things were going, she always got the same reply: “Everything’s great, mum.” It was only after his death that she found out he was three years in arrears on the payments for his flat.

After his death, when she visited to make sure the appliances were switched off, she found the fridge was almost empty. “Inside there was an apple, three quinces, a pot with plain pasta, and a half-finished yogurt. In the freezer, no more than200 grams of berries. And four boxes of cereal,” Larisarecalls.

Konstantin says Kotov was “always in the red”. Svetlana says she once invited him on a trip to the Volga, but he baulked at the plane fare. “Do you know what kind of feast I could get for that money here?” she remembers him saying, regretting now not paying for the tickets herself.

The move into tourism was born out of disillusionment with the Skolkovo start-up incubator, Konstantin says. He may have invested and lost inheritance money in the fish project, too. His mother agrees, and says her son started the new business “not for profit, but out of desperation.”

“He couldn’t understand what he was accused of”

Kotov told his mother that he was planning to start a tourism business in the summer of 2024. "I said: son, you're an economist, you're a psychotherapist, you're a videographer. What do you need this for?" she recalls.

In March last year, he had officially registered his company, which he called “Men Travel”. By then, the Supreme Court had already declared the supposed ‘international LGBT movement’ an extremist organisation and banned it in Russia.

But social media accounts named “Group Tours ‘Gays Together’” and “Men Together Tourist Club” were created two years before that. Andrei appears on a Telegram post in July 2022 as the leader of a tour to the Volga. Yet not all the account of cheerful trips were true accounts of what took place – and some of the trips hadn’t taken place at all.

In one video posted to Telegram, young men with blurred faces are captured swimming and having fun in the water, posing for the camera. We identified one of the participants, who confirmed his identity, but said he was an actor, and was paid for the shoot after responding to an advertisement. He and others were told the video was being shot for state television.

"You need to swim, ride on a boat, sunbathe, etc. Clothing: shorts, sleeveless t-shirt. Bring swimwear, sunglasses, towel. Payment 1000 rubles + travel," the advert stated.

When learning that the footage had been published as part of a ‘gay tour’ the man we spoke to responded with a profanity.

A video entitled “11 Days in Turkey” also describes a tour that didn’t happen, in a film employing actors and extras. Participants were paid to travel to the Turkish coast, given a fee and free lunch. An advert called for men with a “European appearance (not overweight).”

“This descent was cooler than sex!” claims a comment on a mountain biking video in the hills near Sochi on the Black Sea. It purports to be from another organised tour. But the video was copied from the an extreme cyclist’s YouTube channel and used without his permission.

Another video from Kotov’s travel agency was taken from the site of a gay activist in Croatia (who did not respond to a request for comment).

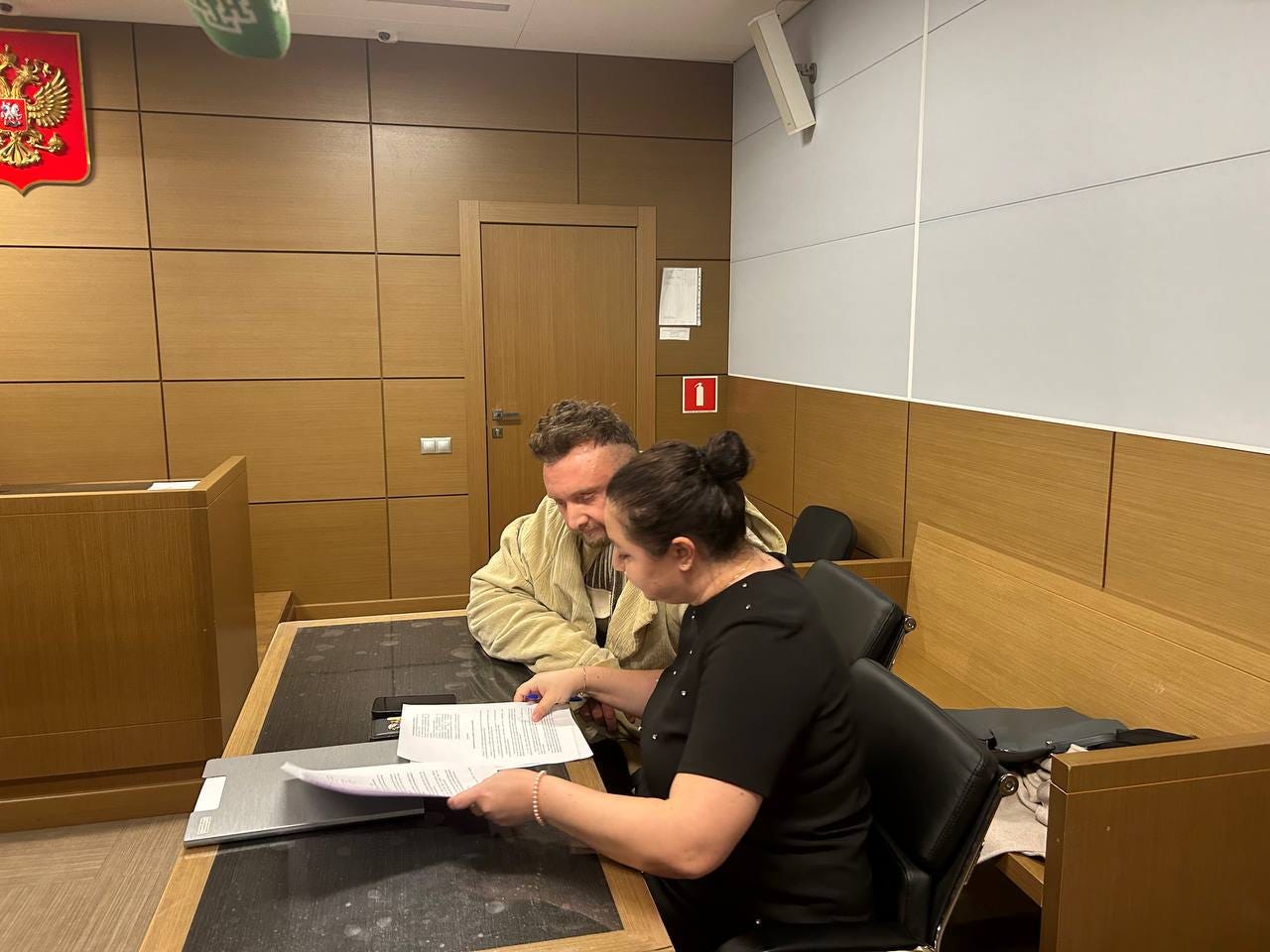

None of Kotov’s relatives knew of the social media accounts. His lawyer, Leysan Mannapova, says that Kotov said he was the sole tour organiser and founder of “Men Travel.”

His friend Svetlana said Kotov did everything on his own. She suggested the fake trip videos may have been made to drum up interest to get a tour group together. The only genuine trips he managed to organise were weekends not far from Moscow in mid-2024. He told his lawyer he had organised everything himself and sold the tours at cost.

"He simply couldn’t understand that this could be considered extremism,” the lawyer Mannapova tells the BBC. “For him, it was not just a shock: he couldn’t even understand what he was being accused of.”

Although a series of laws have been passed in recent years targeting gay people, Kotov’s friends say he didn’t take the news seriously: he treated politics as a game which you need to filter out.

More on the crackdown on LGBT rights in Russia:

"For some reason, he didn't think any of this could harm him,” Konstantin says. “His naivety was truly fantastic. But he thought, 'Well, I'm a good person, nothing can happen to me, I don't hurt anyone, I don't bother anyone,'

"Andrei’s wasn't some sort of protest movement,” Konstantin adds. “He just wanted to be himself."

His mother Larisa said her son was “always with girls” and had nothing to do with gay people. She believes her son was a victim of the unfortunate choice of name for his tourismagency, ”Men Travel”.

"What they're writing about him makes my hair stand on end. He's a child. He's a grown-up, overgrown child," she repeats.

"Speak to any policeman like a brother, lovingly, kindly...”

The social media account that posted ads seeking extras for commercial videos in October last year began to publish instructions on how to behave during police raids at night clubs.

"First of all, any police officers who arrive to inspect the nightclub and ask me something ARE OBLIGED to first introduce themselves and show their documents, and I will definitely ask them about this (if they forget), and I will write down all the names, positions, and departments in my phone so that I have someone to file a complaint against later," begins one of his text instructions.

Kotov recommended his readers follow the example of Gandhi when considering how to respond to the threat of violence.

"If everyone in the nightclub did what I do, and then filed complaints with two or three local authorities and also sent two or three letters to the press... don’t you think the situation would change? I’m sure it would.”

Kotov said the police were too busy to arrest and take people to detention centres. Media reports were wildly exaggerated, he claimed.

"Speak to any policeman like a brother, lovingly, kindly, because they are also people. Yes, yes, just like us... and among them, there are also 'our' people... If necessary, appeal to their bright side, their conscience, and their nobility...

"And friends, DO NOT be afraid, DO NOT be afraid, DO NOT be afraid...” the text continues. “The main law of life isdo not be afraid, and know your rights! Otherwise, you are a trembling creature and are without rights. And I believe that gays are very brave, smart, cunning, and resourceful, because they have had to survive in this society since birth and are super-resilient."

When masked police came to search his apartment, they beat Kotov and tortured him with a taser. "Despite my training as a psychotherapist, I am still unable to say what degree of PTSD was inflicted on me and why all these procedures were necessary," Kotov said in court during his pretrial hearing.

He was charged with organising and participating in an extremist community. The court remanded him in pre-trial custody on December 2nd for two months. By the end of the year, Kotov had additionally been charged with producing child pornography. Investigators claimed to have found videos on his phone that showed he had secretly filmed naked children.

A BBC source stated that they were not filmed surreptitiously but in a public place. Kotov’s lawyer, Leysan Mannapova, says she has not seen the alleged videos herself, since case materials are not made available to the defence until the pre-trial investigation is complete or the case is closed. But she points out that under Russian law, any image of a child’s genitalia is considered by definition pornographic.

“A crime is deemed to have been committed simply by the fact of taking such a photo or video, even if you did nothing with it. Even if it was in a public place and the parents were bathing the child," she says.

Organising an extremist community is punishable by up to 10 years in prison. “Using a minor for the purpose of creating pornographic materials" carries a sentence of up to 15 years.

After lunch on December 29th, Leysan Mannapova received a call from the case investigator, who informed her that her client Andrei Kotov had taken his own life at four o’clock that morning.

"I would lie down in the coffin in his place"

The last time Larisa Kotova spoke with her son on the phone was the day when the police came to arrest him.

Their conversation broke off abruptly. Larisa thought he must have spilled his coffee or something. “I was going to write him a cross letter, and say you can’t just put the phone down on your mum like that, half way through a call.”

She found out about her son’s arrest from the news.

During the few weeks to come, before his death, she wrote Andrei four letters at the detention centre but didn’t receive an answer to any of them. She says she told him to apply to join the army and fight in Ukraine, “but it turns out that with charges like he faced, they wouldn’t have taken him for the Special Military Operation anyway.”

Larisa Kotova has still not received her son’s body for burial. Forensic examinations into his death have not been completed. The new year holidays in Russia delayed matters further.

Larisa is an elderly woman – 78 years old – and doesn’t know where to find the money to bury her son. When she spoke with the BBC, she said she had only 4000 rubles (roughly $40) in the bank, and planned to spend them on the weekly food shop. The funeral fees are estimated at 150,000 rubles – about $1500.

“I am panicking, I’m a pensioner,” she says, clearly distressed. “I honestly don’t have any idea how to bury him.”

Larisa repeats over and over that Andrei was “my treasure, my hope, my support.” She doesn’t know what to do with all the complex and expensive fish farming gear that fills up his flat on the outskirts of Moscow. She is desperately trying to find someone to take it. The Skolkovo innovation hub has not responded to a letter she sent asking them if they want his patented equipment.

"Andrei was not just a son but a friend, a counsellor, a teacher,” she says. “We constantly communicated, shared our thoughts on books, films, and holidays. It's awful without him,he could calm me, comfort me, inspire me; we're so similar. I would lie down in the coffin in his place, just for him to be alive."

She asks during the interview to help her pass on his inventions into good hands: “so that his work doesn’t go to waste,” she pleads.

"I cannot bring myself to throw it all away. It's his work, it's his life, I can't just fling it on the dump."

Read this story in Russian here if you are outside Russia, and here if you are in Russia.

English version edited by Chris Booth.

From the Moscow Conservatoire to death in a prison cell in Russia’s Far East

Pianist Pavel Kushnir’s fatal hunger strike went unnoticed as the West exchanged prisoners with the Kremlin.