LONG READ: Tajikistan's terrorism problem

Why have so many Tаjiks been involved in terror attacks this year? The BBC meets the families of the men accused of the Moscow concert hall atrocity and asks security experts what's going wrong.

By Grigor Atanesian.

Muhammadsobir Fayzov was only 19 years old when he was arrested on charges of involvement in the March 22 attack on Moscow’s Crocus City Hall. Prosecutors say the former hairdresser was one of four Tajik men who rampaged through the venue shooting and slashing concert goers at random before setting fire to the building. The attack left 145 dead and many more injured.

How could a young man from an educated family and who dreamed of becoming a doctor, carry out an act of such appalling violence? How did a football fan with no apparent interest in religion end up involved with IS-Khorasan - the branch of the so-called Islamic State group that claims to have organised the Crocus attack?

For more than a decade now, many Tajik parents have been asking themselves similar questions as thousands of young men have joined the ranks of IS, first fighting in Iraq and Syria and now increasingly accused of carrying out terror attacks in cities across the world on behalf of its affiliate in Afghanistan.

The BBC has travelled to the villages where the four alleged Crocus attackers grew up and has also spoken to academics and security experts who follow Tajikistan closely, to try to understand why Central Asia’s poorest country, is losing so many young people to extremist violence.

The hairdresser

In Mahmadshoi-Poyon village on the outskirts of Dushanbe, the gates to the house where Muhammadsobir Fayzov grew up are closed.

On the day the BBC arrived his mother had been called in for questioning by the Tajik security services and the whole family were very reluctant to speak to the media.

The youngest of the Fayzov family’s five children, Muhammadsobir is also the youngest of the four Tajik men accused of carrying out the Crocus Hall attack.

When they were remanded in custody in Moscow on March 24, Muhammadsobir was carried into the courtroom barely conscious, still wearing a hospital gown and with a catheter clearly visible. During his capture, he had been beaten so severely that he lost an eye.

In a brief conversation outside the family home, one of Muhammadsobir’s brothers tells the BBC he had gone to Russia two years ago, was working as a hairdresser and that he wasn’t religious. His grandmother, looking bewildered, adds that her youngest grandson was a big football fan.

Down the road at school number 74, Muhammadsobir’s teachers are also shocked. Everyone knew the family well. His father had taught Russian language here before going to Russia in search of work, and his mother, also a teacher, had run the school library.

His teachers remember an ordinary boy who loved maths and football and who dreamed of becoming a doctor.

“I don’t remember him being interested in religion or going to prayers,” says the headmaster, Abdulaziz Abdulsamadov. “Unless he changed a lot after he left school, all I can say is that his behaviour was normal during his studies and it’s impossible to believe that he did something like this.”

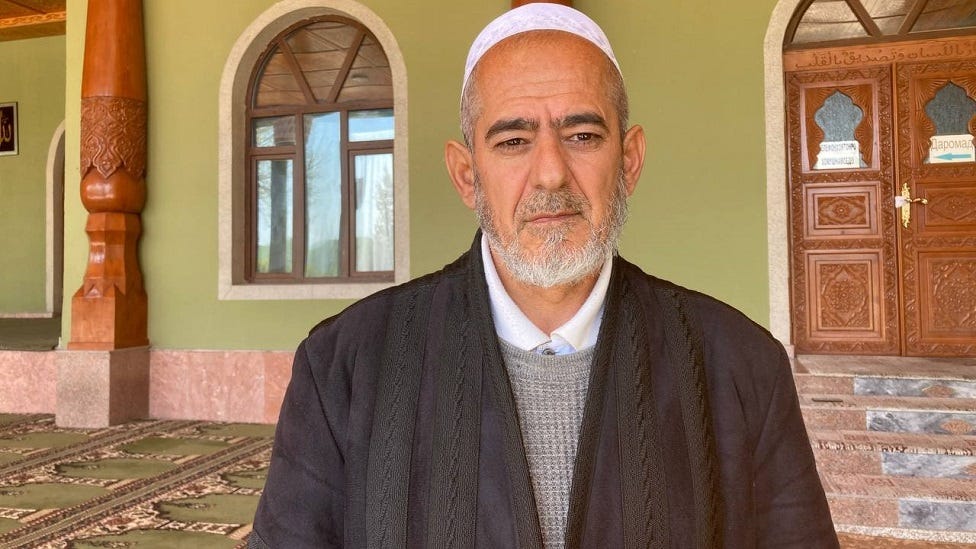

It’s the same story in the local mosque where Imam Saidrahman Habibov is struggling to process the news. He also remembers the family well and says that unlike his father, Muhammadsobir was not religious.

"His father used to come to the mosque,” he says. “Sometimes one of his brothers would come along too. On Fridays, he would set up a table outside to sell prayer beads and perfumes. Sometimes Muhammadsobir would be there helping his brother.”

Judging from his social media posts, Muhammadsobir’s last known place of employment was barbershop called My Style in the town of Teykovo in Ivanovo region, northeast of Moscow.

The shop was in a single-story commercial building, next door to an off-license, a florists, a hookah lounge, a micro-loan business, and a takeaway kebab shop.

In the aftermath of the Crocus City attack the barbershop shut down after a wave of threats and hate mail.

The taxi driver

In another village, called Galakhona, on the southern outskirts of Dushanbe, a tiny white-washed two-room house with a corrugated iron roof stands empty.

This is where 32-year Dalerjon Mirzoyev, the oldest of alleged Crocus attackers and the alleged ringleader, lived with his wife and four children.

When he appeared in court in Moscow in March, he was bruised and battered and appeared to have the remnants of a plastic bag round his neck after an FSB interrogation session.

Dalerjon’s parents, Barot and Gulrakat, live just down the street, and they are also in complete shock at the news from Russia.

"I can’t believe my son would do something like this,” his mother says. “He couldn’t kill a chicken, he wouldn’t even hurt an ant.”

The family told the BBC that two years after he left school, Dalerjon had got his driving license, and for the past ten years he had been working in Russia for six months of every year. Most recently they said, he’d been driving a taxi in Novosibirsk.

Gulrakat Mirzoyeva said she had last spoken to her son on 17 March, just five days before the Crocus attack.

“He said he was planning to leave Russia on 20 March, she says. “He said he was worried that they were deporting Tajiks, and he didn’t want to risk not being able to go back to Russia again. He said he should be home by 25 March.”

Some Russian media outlets have reported that Dalerjon’s Russian residence permit had expired, which would tie in with what he told his mother.

This is the second loss for the Mirzoyev family. Their older son Ravshanjon, moved to Russia in 2016, at the age of 30, and has been missing ever since.

“The doctors told him that he had problems with his lungs,” says the elder Mr Mirzoyev. “He was in hospital in Moscow for 7 months. He was discharged in October or November 2016 and he told us he was going to catch a bus to St. Petersburg. We never heard from him again.”

The Tajik authorities say rather than leaving for St Petersburg, Ravshanjon had actually left Russia to fight for IS in Syria. He is now on the terrorist wanted list and some reports say he was killed in 2020.

The family has not been able to confirm any of this independently, and they insist that Dalerjon was not in touch with his brother.

The day after the Crocus attacks, Dalerjon’s mother, wife, mother-in-law and brother were all called in for seven days of questioning by the security services. His father was not detained, because of his poor health.

His wife has now returned to her mother’s house. She is said to be deeply shocked and distressed and is being cared for by doctors.

The builder and the baker

The back stories of the other two Crocus Hall attack defendants both follow a similar pattern.

After their arrest in Russia’s Bryansk region on the night of the attack Saidakram Rajabalizoda, 30, and Shamsiddin Faridun, 25, were pictured in graphic videos leaked to the Telegram messenger site, being beaten, and brutalised by Russian security agents.

Rajabalizoda’s ear was cut off and forced into his mouth, Faridun was severely beaten and electrocuted.

Born in the village of Chamanzar, 25km east of Dushanbe, Rajabalizoda had been working on and off on construction sites in Russia since he was 18.

Some of the money he sent back paid for the green-washed two-storey home where his wife lives with their two children, and his elderly mother. The mother, who has heart problems, still doesn’t know what has happened to her son.

Rajabalizoda’s uncle, Saidmukhtor, told the BBC that in 2018 his nephew had been deported from Russia for breaking immigration rules and was banned from re-entering the country for five years. He had only just returned to Russia in January this year.

His uncle told the BBC Rajabalizoda had called home on January 6, to say he had arrived safely. The next time his family saw him was on the news after the Crocus attack.

Shamsiddin Faridun, 25, was born in the village of Loyob, 40 km northwest of Dushanbe. He was married with a young child, and before going to Russia in search of work, he had been employed in a local bakery.

None of his immediate family wanted to speak to the BBC, as all of them had been questioned by the security services.

Local people told us Faridun had done three previous stints as a migrant worker in Russia, and that he had also spent time in prison after being convicted on sexual assault charges, something his family says he strongly denies.

‘A good boy who never got in trouble’

“If you look back at the testimonies of [Tajik] family members whose sons went to [fight for] the Islamic State in Syria or Iraq a decade or so ago, they’d often say that he was a good boy, he wasn't religious, and he never got in trouble,” says Professor Edward Lemon, a Central Asia specialist at the Texas A&M University, in the US.

Lemon has been studying the radicalisation of young men in Tajikistan for the past two decades. He says the reactions of the parents of the four alleged Crocus attackers, and others like them are not just motivated by denial or a desire to protect a family member.

Over the past three decades a whole host of economic, political and geopolitical factors issues have come together to make young Tajiks especially vulnerable to recruitment by extremist groups.

It’s led them into worlds their parents find impossible to even imagine, and has turned far too many ‘good boys’ into killers.

According to official data from Tajikistan, more than two thousand of its citizens have fought for IS in Syria and Iraq.

When the group was defeated, a spin-off branch in Afghanistan, known as IS-Khorasan or IS-Khorasan Province (IS-K or IS-KP for short), became the new destination for radicalised men. ‘Khorasan’ is the name of an ancient region covering parts of what is now Afghanistan, Iran, and the five Central Asian countries.

A recent report in the New York Times estimated that around half of new recruits to IS-K are now from Tajikistan.

Edward Lemon says this is impossible to verify, but could be a realistic estimate if it includes not only Tajik citizens but also ethnic Tajiks from northern Afghanistan.

If high-profile international terror attacks in the past year are anything to go by, then Tajik nationals have clearly been playing a prominent role.

In addition to Crocus City Hall, young Tajik men have also been implicated in the series of explosions which claimed the lives of up to 100 people at a memorial event in Kerman, in Iran, in January, as well as the gun attack on a Catholic church in Istanbul, in Turkey, which left one person dead the same month.

The Founder of the Peace

A key factor to understanding the problems Tajikistan is now facing, lies in the country’s traumatic recent past.

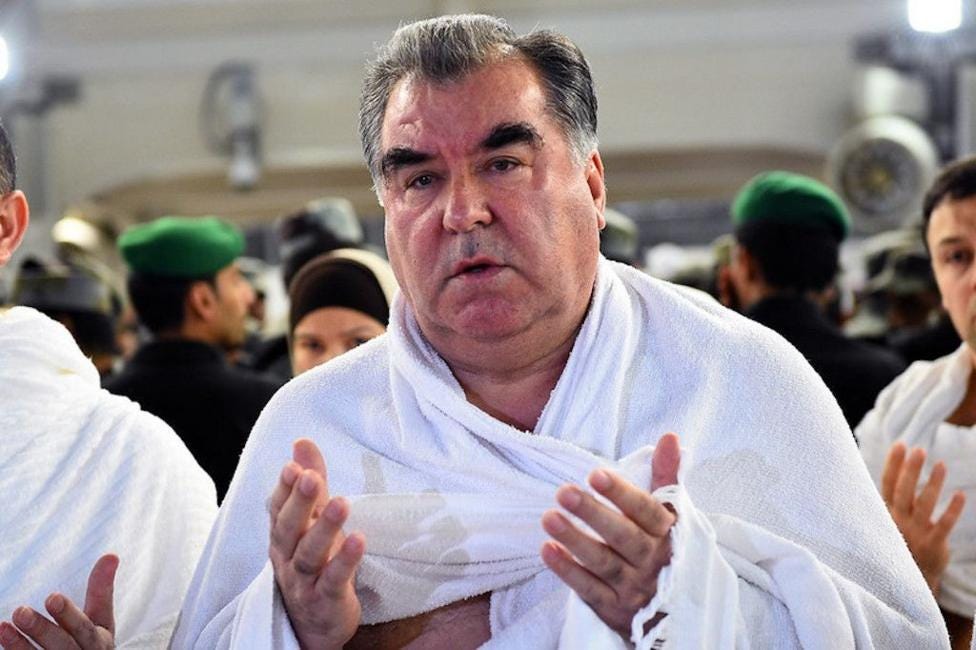

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Tajikistan was engulfed in a brutal and complicated civil war, which for shorthand’s sake, pitted an opposition, led by the Islamic Renaissance Party (IRPT), against a Soviet successor government, headed from 1992 by Emomali Rahmon (then Rakhmonov).

The war ended in 1997 with a peace deal, Rahmon remained in place as president and continues to lead Tajikistan to this day.

The Islamic Renaissance Party initially received seats in parliament, but over the years it was increasingly pressurised and marginalised until finally, in 2015 the party was declared a terrorist organisation.

Rahmon remains in power thanks to a number of constitutional amendments - which have enabled him to keep standing despite previous limits on the number of terms a president could serve.

In 2015 he was proclaimed ‘Founder of the Peace and National Unity, Leader of the Nation’ - a title which is not subject to any constitutional restrictions.

As ‘Leader of the Nation’ Rahmon has built a system in which political Islam is completely banned, and religion is subordinated to the state, with its role in society strictly regulated.

On one hand, Islam is recognized as the state religion, and Rahmon himself has performed the Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca) four times. One of the largest mosques in Central Asia, designed to accommodate over 100,000 people, was built in Dushanbe.

At the same time, the state insists on a secular way of life, appearance, and behaviour. Even wearing the hijab or having a long beard is considered a violation of the law.

The place allotted to religion in society has consistently diminished. Hundreds of mosques have been closed, and women and minors are prohibited from attending them. Imams at the state-run mosques receive their salary — and talking points for Friday sermons — directly from the state.

The government not only keeps a firm check on Islam, but also seeks to create cultural alternatives. In 2006 Rahmon delved deep into Tajikistan’s ancient pre-Islamic past, declaring the "Year of Aryan Civilisation".

Streets were adorned with posters dedicated to the Aryan ancestors of Tajiks. The president de-Russified his name: instead of the Russified "Rakhmonov," he reverted to the original, Rahmon. He also decreed that "ancient Aryan" holidays would be celebrated from now on.

In reality however it is clear that neither the state-controlled version of Islam, nor Aryan history are anywhere near as attractive to young people as the independent, politicised and often radical narratives which have been spreading like wild-fire on social media.

Well-known Islamist bloggers in Tajikistan now have millions of followers, and talk about issues of concern to the wider Islamic world — including most recently Gaza and the war between Israel and Hamas.

The most radical among them also accuse the government of persecuting conservative Muslims, calling President Rahmon an “enemy of true faith”.

Back in 2015 Edward Lemon was already sounding the alarm about what was happening in Tajikistan.

“Government repression of religion in Tajikistan has produced counterproductive results and served to push more citizens into the arms of radical groups,” he wrote.

“By examining the profiles of Tajik fighters, it emerges that a cocktail of alienation, marginalisation and vulnerability lures them into travelling to Syria and Iraq,”

Back then, Islamic State militants had seized vast territories in the two countries declaring them a new ‘caliphate’ and attracting followers from all over the world.

By 2019, IS had been all but defeated in the Middle East, but in Afghanistan the affiliated group, IS-K, was beginning to attract new recruits.

The fact that Tajikistan shares a long land border with Afghanistan, as well as linguistic and cultural roots with the country’s Dari-speaking population has clearly facilitated this process.

Poverty, Russia and Afghanistan

Another key factor drawing young Tajiks into extremist groups, is undoubtedly poverty.

Tajikistan remains the most economically challenged of all the post-Soviet states. Every year hundreds of thousands of Tajik men and women, go to Russia in search of work — routinely enduring tough working conditions, hostility, and prejudice.

According to official data, there are now over a million citizens of Tajikistan working in Russia. The total number of migrant workers in Russia is estimated to be between 12 and 14 million, of which as many as four million are thought to be undocumented.

For Tajik men the pressure of finding a way to earn enough money to support large and often extended families, can be huge.

Despite his dreams of being a doctor, Muhammadsobir Fayzov apparently had little choice but to pack his bags and head for Russia to make some money at the age of just 17.

His other three co-defendants had all previously tried and failed to make a living at home in Tajikistan.

All four were supporting a network of wives, children, parents, siblings and elderly relatives, all dependent on remittances being regularly wired back home.

It’s a heavy burden on young shoulders and not surprisingly many migrant workers find themselves turning to religion for solace, Edward Lemon says.

Poorly educated young men with only a very basic understanding of Islam often prove an easy target for the extremist propaganda they come across online in Russia.

Of course it’s not just poor boys from villages who get radicalised.

Lemon and his colleagues keep a database of ISIS recruits from Tajikistan, which also includes the children of state officials, middle-class men, medical students, and residents of Dushanbe and Khujand, the country's two largest cities.

But according to Lemon's data, the majority of future jihadis are migrant workers who are recruited in Russia and then sent to overseas bases, mostly through Turkey.

Afghanistan has now become the centre of such bases. Although the Taliban are arch-enemies of IS and have vowed to expel them from the country, the group does not fully control all parts of Afghanistan and does not have the drones and other resources which were successfully used to defeat IS on the ground in Syria and Iraq.

The Russian-lead regional security grouping, the Collective Security Treaty Organisation, of which Tajikistan is also a member, recently warned that the terrorist threat from Afghanistan was rising and that it had identified a growing network of extremist training camps in northern Afghanistan, close to the Tajik border.

IS-K and the Tajik connection

Until last year, one of the leading members of IS-K was a Tajik citizen called Sayvali Shafiyev, according to a report by the UN Secretary-General, published in January.

The report said Shafiyev was arrested in Turkey in 2023. But another Tajik national, Shamil Khukumatov, remains at large and is said to be one of the group’s most active propagandists and high-ranking recruiters.

In March of this year, IS-K published the first Taijk-language version of their propaganda magazine ‘Voice of Khorasan’ on the messenger app Telegram.

"Do you thirst to become martyrs?" it asked, calling on people to join the group. In one article the magazine referred to President Rahmon as "shaitan" (devil) and criticised his "godless regime" for what it said was a "betrayal of Islam."

In one of the illustrations, Rahmon is depicted as a puppet of Russian President Vladimir Putin, and Russia is referred to as a colonial occupier.

Calls for retribution against Russia are a common theme in the group's propaganda. It accuses Moscow of killing innocent Muslims during wars in Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Syria. In addition, propaganda videos feature footage of Russian officials meeting with the Taliban — sworn enemies of IS-K.

Who is next?

A week after the attack on the Crocus City Hall, IS-K released a propaganda image showing a shadowy figure looking at screens showing pictures of London, Madrid, Paris, and Rome.

"After Moscow, who is next?" read a caption in Arabic and broken English.

Security experts say this is not just bravado and they point to the fact that IS-K has already attempted to carry out attacks in Europe.

In July 2023, German and Dutch law enforcement agents arrested a number of men from Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan on suspicion of planning acts of terrorism.

And in December 2023 and January 2024 another suspected IS-K cell was arrested, allegedly planning an attack on Cologne Cathedral.

A key focus for concern now are the upcoming European Football Championships, in Germany in June and July, and the Olympic Games in Paris, in July and August.

After the Crocus City Hall attack, French President Emmanuel Macron convened an emergency meeting and raised the level of the terrorist threat to "exceptional." He said that the same group had already attempted attacks against his country.

Paris has already mobilised police, military and civilian specialists from 45 countries to secure the Olympics.

Wake up call to the world

In the US, there’s also growing concern about IS-K and the potential for the group to carry out attacks in Europe using recruits from Central Asia.

In April Admiral James Stavridis, former NATO forces supreme commander in Europe, wrote a column for the Bloomberg news agency saying the Moscow Crocus City Hall attack was a ‘wake up call to the world”.

He said it was vital that the US tried to cooperate with Russia, China, and even the Taliban in Afghanistan to counter the threat.

"When I was NATO’s supreme commander, I had serious and productive talks with senior Russian officials — including the head of their armed forces — about cooperating on counterterrorism,” he wrote.

In the aftermath of the Crocus City Hall attack, much was made of the warning the US had issued just weeks earlier, that a terrorist attack on a public event in Moscow was imminent.

An international relations expert close to the US intelligence told the BBC “the US would be pleased if Russia reciprocated” its warning of the IS-K attacks, but so far Russian officials have been reluctant to do this.

The conflict in Ukraine and Vladimir Putin’s insistence that Russia is at war with NATO and the West, is a hugely complicating factor.

"The Russian narrative is that the US helped create ISIS and IS-K to undermine Russia and its allies, so it does not believe that the US is acting in good faith in countering it," says Edward Lemon.

Moscow, meanwhile, is continuing to push the line, that the Crocus City attacks were masterminded by Ukraine.

After their shocking first court appearance, the four Tajik alleged perpetrators appeared on camera again the following month in a video released by the FSB.

Although their outwardly visible injuries appeared to have healed, all four men were clearly speaking prepared lines under duress.

They all repeated the same story that the attack had been planned in Ukraine, and that they were heading for the border when they were captured.

In May, a Moscow court extended their detention for another three months.

Once again Muhammadsobir Fayzov, who had just turned 20, was brought to the court building in a wheelchair.

In footage aired on Russian state-controlled TV, he appeared unable to move.

No date hаs been set for a trial.

Edited by Jenny Norton

Additional reporting by Sohrab Zia.

Read this story in Russian here.

Previously…

Free to kill: where were Russia’s law enforcement officers when they were needed?

How were the gunmen at Moscow’s ‘Crocus City Hall’ able to calmly murder or cause injury to 551 people - and drive away unhindered? Russia’s security services have questions to answer.

“Crocus City Hall” attack: "I watched the line of fire moving towards people."

The BBC talks to people who witnessed the attack on "Crocus City Hall" - and those who escaped it. Many thought they were hearing fireworks before the concert. Until they saw the gunmen.