SPECIAL REPORT: “Russia should leave”: Is there a future for Moscow in the new Syria?

What do Syrians really think about Russia, and does Moscow still have a future here? Ten days on from the fall of the Assad regime our correspondent reports from Damascus and Douma.

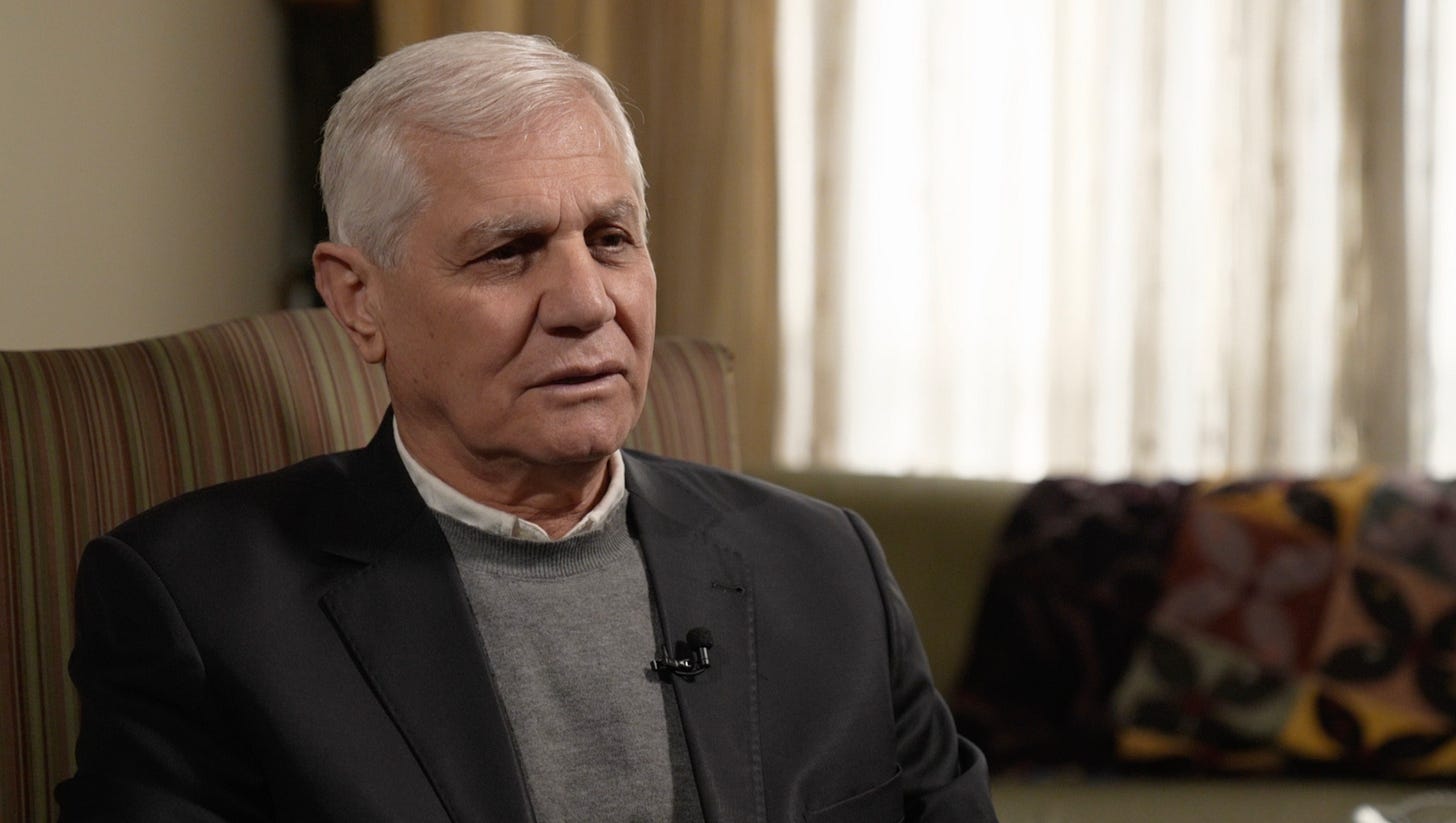

“Russia's crimes here were indescribable,” says Ahmed Taha, a key rebel commander in the city of Douma, six miles north-east of Damascus. “It was indescribable criminality.”

He’s standing on a desolate street of bombed-out apartment buildings.

Douma was once a prosperous place — capital of a region known as the breadbasket of Damascus. But now large parts of it lie in ruins after some of the fiercest fighting in Syria’s fourteen-year civil war.

Entire residential districts and schools have been reduced to rubble. Much of the destruction was reportedly the result of Russian airstrikes.

Before the war, Mr Taha was a civilian — a contractor and tradesman. He took up arms in 2011 after peaceful protests in Douma were brutally suppressed by the Assad regime, and he went on to become one of the leaders of the city’s armed opposition.

When the Islamist coalition called ‘Army of Islam’ (Jaysh al-Islam) took control of the area, Mr. Taha refused to accept its leadership — and remained opposed both to the regime and the group.

In 2018, after five brutal years under siege by the Syrian army, the rebels finally agreed to surrender in exchange for safe passage to Idlib. Russian military police were deployed to Douma as guarantors of the deal. By that time, over 40% of the city was destroyed, and many faced hunger.

After six years away, Mr Taha has finally returned home to Douma. He came back as part of December’s lightning rebel offensive led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) Islamist group and its leader Ahmed al-Sharaa.

As he takes us for a ride around the city in his battered Mercedes, it’s clear that life is already beginning to return to Douma.

In the streets around the main mosque, shops and market stalls are doing a steady trade in fruit and vegetables? As we make our way through the crowds of shoppers Mr Taha is constantly stopped by locals who want to ask him something or simply say hello.

“We are back home in spite of Russia, in spite of the regime and all those who supported it,” he says.

And he is adamant that all remaining Russian troops should leave Syria.

“For us, Russia is an enemy,” he says.

On the streets of Damascus we meet many people who seem to agree with Mr Taha’s view of Russia.

Ten days after the fall of Assad, the city still feels euphoric. The three-starred flag of the opposition — once the symbol of the struggle for independence from France in the 1930s, is flying everywhere.

At the ancient Umayyad Mosque, crowds are gathering for Friday prayers. The event has become something of a weekly celebration of the end of the Assad regime, and the large open courtyard with its 8th century mosaics is packed with people. Men, women, Damascenes, people from all over the country, and foreigners all mix freely.

Abu Hisham, from Hama, in central Syria, has come to the capital with his friends to join in the celebrations.

“The Russians came to this country and helped the tyrants, oppressors, and invaders,” he says.

Even the leaders of Syria’s Christian communities — whom Russia vowed to protect — say they have seen little help from Moscow.

We are granted an interview with Ignatius Aphrem II, the Patriarch of the Syriac Orthodox Church. He receives us in a complex adjacent to St George's Cathedral in the heart of Bab Touma, the ancient Christian quarter of Damascus. It is a large but simple neoclassical building with a cross at the apex and a square relief depicting St George slaying the dragon.

“We did not have the experience of Russia or anybody else from the outside world protecting us,” he says. “The Russians were here for their own benefits and goals.”

Around Bab Touma, the Christmas decorations are up — although preparations for the holiday season seem notably less commercialised than in most European cities. Catholic boy scouts with their fleur-de-lis ties are collecting donations.

Baker Samer is selling his famous bread that is also used in the liturgy, and churchyards are decorated with Christmas trees.

At the La Capital restaurant, customers — not only Christians but also young women in hijabs — take selfies in front of a neon sign saying 'Merry Christmas' that hangs above a large mirror. But the festive atmosphere hides deep scars.

At the start of the civil war in 2011, Syria’s Christian population stood at an estimated 1.5 million. Now Christian organisations put it at just 300,000 — a five-fold decrease.

The fact that this happened despite a Russian intervention, supposedly aimed at protecting Syria’s minorities, has left many people in Bab Touma feeling betrayed.

“When [the Russians] came in the beginning, they said, 'We came here to help you’”, says Assad. “But instead of helping us, they destroyed Syria even more.”

So what does all this mean for Russia, and for the future of the Tartus naval base and the Hmeimim air base which Moscow holds on 49-year leases on Syria’s Mediterranean coast?

Despite his own personal bitterness towards Russia, Ahmed Taha, the rebel commander from Douma, told us he understood that it was important for Syria’s new interim leaders to think strategically about the country’s future relationship with Moscow.

And “strategic’ was also how the country’s new leader Ahmed al-Sharaa described relations with Russia in his first sit down interview with the BBC on 18 December.

It’s a phrase Russia’s foreign minister Sergey Lavrov was quick to seize on:

“I must note that the head of the new Syrian government, Ahmed al-Sharaa, has recently talked to the BBC. In his interview, he described Syria’s ties with Russia as long-standing and strategic. We share that approach. We have much in common with our Syrian friends,” Lavrov said.

Syrian defence analyst Turki al-Hassan, a retired Syrian army general and long-time observer of relations with Russia, also takes a pragmatic approach.

The walls of his apartment in a residential district of Damascus are lined with bookshelves, and it’s clear that his perspective is influenced by history, and not the current news agenda.

Syria’s military cooperation with Moscow predates the Assad regime, he tells us.

“From its inception, the Syrian army has been armed with Eastern Bloc weapons, especially from the Soviet Union, and now from Russia.”

Virtually all the equipment and weapon systems used by the Syrian military today were produced by the Soviet Union or Russia, her reminds us.

Between 1956 and 1991, Syria received some 5,000 tanks, 1,200 fighter aircraft, 70 ships and many other systems and weapons from Moscow totalling over $26 billion, according to the Russian estimates. More than half of the sum was left unpaid when the Soviet Union collapsed, but in 2005, President Vladimir Putin wrote off 73% of this debt. Russia continued supplying weapons.

Now, rebuilding the military for a new Syria will either require complete rearming or a continued reliance on Russian supplies, which will necessitate some kind of relationship between the two countries, al-Hassan said.

Russia’s two Syrian military bases are crucial hubs to support its ongoing presence across Africa, particularly in Libya, the Central African Republic, Mali, and Burkina Faso.

And as ordinary Syrians hope for an end to further hostilities, some think a continued Russian presence might help to keep the peace in their country.

“We welcome the Russians here to keep our state strong, and to keep our army strong,” the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch Ignatius Aphrem II tells the BBC.

“What can Russia offer the new regime? And what can the new regime do in terms of political and military cooperation?”

It will be the answers to these questions that determine future relationships, says Turki al-Hassan.

Watch Grigor’s report on BBC News Channel:

The cost of Putin’s military venture in Syria

The BBC can reveal that hundreds of Russia’s most highly-trained military specialists joined their final battle in the Middle East – and will not be returning home.

This title should have stopped at, "Is There a Future for Moscow?"

…it’s a joke right ?