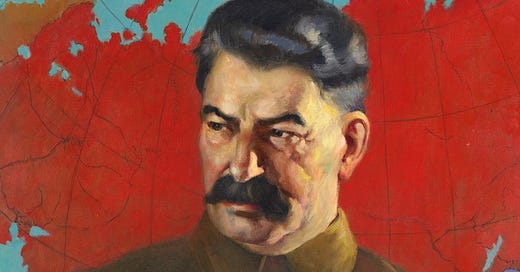

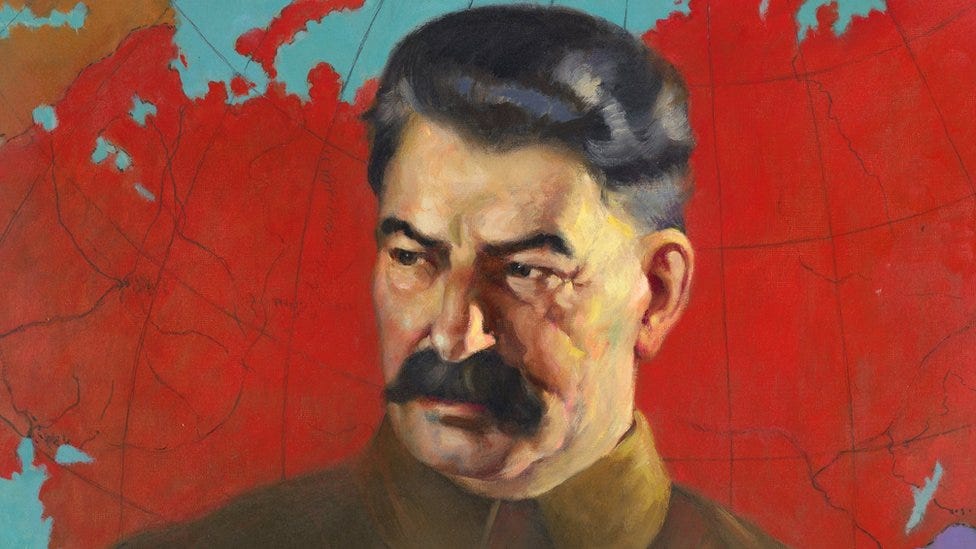

Anniversary of Stalin's death: The teens who challenged the Soviet dictator - and lived to tell the tale

Joseph Stalin, infamous for his bloody purges and rule of terror in the Soviet Union, died 70 years ago. We look at the case of three teenage boys who did challenge him - and survived.

By Andrey Zakharov.

When Soviet leader Joseph Stalin died on 5 March 1953, it seemed like the whole of the USSR plunged into mourning. But behind the grieving exterior, there were mixed attitudes towards the leader under whom millions of people had perished in purges and famine, and millions more endured poverty. In one case, Stalin's authority was challenged by three boys.

During his nearly three decades in power, he sought to project an unquestioned authority, and cracked down brutally on dissenting voices.

Yet, protests did take place in the Soviet Union. They were not frequent or large in scale, but they did indicate that many disagreed with the totalitarian regime.

One such event took place in Chelyabinsk, an industrial city in the Urals, a mountainous region separating Russia's European and Asian parts. The city was home to a tractor-building plant.

One day in the spring of 1946, three teenagers set about putting up flyers in the centre of the city. Local residents queuing for food observed them wearily.

The boys didn't have any glue, so they used water-soaked bread to stick sheets of paper, torn from their school notebooks, to walls and lampposts.

"Hungry people, rise up to fight!" a schoolchild's hand had scribbled.

One woman in the queue read the flyer. "A clever person wrote this," she remarked.

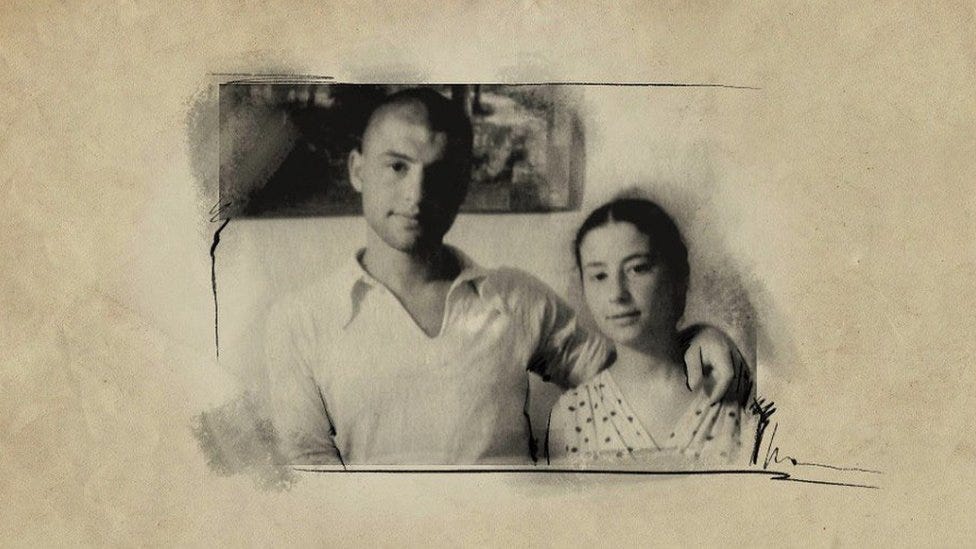

The boys were Alexander (known as Shura) Polyakov, Mikhail (Misha) Ulman and Yevgeny (Genya) Gershovich. They were all 13 at the time, and Shura Polyakov was the leader of the pack.

His family was originally from Kharkiv, in Ukraine, and he'd been evacuated to the Urals with his mother, grandmother, his sister and his aunt. Five of them were sharing one room as the city struggled to accommodate a host of war evacuees.

Shura's dad had been killed in the war. His mum was now supporting the family, working as a lawyer.

Genya Gershovich was also growing up without a dad but for a different reason. He was born in Leningrad, and in 1934 his father was arrested, falsely accused of belonging to an underground network which was planning to overthrow the government.

He perished without a trace.

To keep her two children safe, Genya's mum moved to Chelyabinsk. Despite her husband being "an enemy of the people", she managed to get a job as a secondary school teacher.

Genya's father had been executed before the war, but the family learnt about his death much later.

Mikhail, or Misha, Ulman, like Genya, was also originally from Leningrad. But his family was intact, and both his parents moved to Chelyabinsk at the start of the war to work at the local tractor plant, which at that time was making tanks, not farming equipment.

In Chelyabinsk Misha's family lived in exceptionally crowded conditions, forced to share a room with a stranger. The room was divided by a washing line and a sheet hanging from it.

The three boys went to the same school. Ulman and Gershovich even sat at the same desk in the classroom.

Even though they were only 13, the boys were already reading the works of Marx, Lenin and Stalin as part of their school syllabus. They learnt from these books that accepting injustice was wrong.

They were also carefully studying the lyrics to "The International", an anthem of the workers' movement written in the 1870s by a French revolutionary, which later became shared by all those fighting against social injustice.

The song served as the Soviet national anthem between 1922 and 1944. The boys could not believe that the lyrics, calling on the masses to rise up against social inequality, were not banned in the Soviet Union.

The boys and their families faced severe economic hardship, living on the brink of starvation on post-war food rations.

There was a popular joke in the Soviet Union about the time when leaders of the United States, Great Britain and the Soviet Union, gathered together at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, were discussing what method should be used to execute Hitler, as the war was neared its end.

The joke went that Churchill, the UK prime minister at the time, suggested hanging. Roosevelt, the US president, came up with the electric chair. And Stalin, the Soviet leader, believed the most effective way would be to put Hitler on Soviet food rations. The other two agreed that this would be the most cruel punishment - the punchline of the joke concluded.

But not everyone in the Soviet Union was forced to survive on meagre rations. The three boys had a classmate whose father was the director of the local industrial plant.

The classmate's lifestyle was completely different from theirs: he was brought to school by a driver, he ate much nicer food in his packed lunch, and at his birthday party the boys were able to taste soda water and watch movies by Charlie Chaplin, projected onto a wall.

Needless to say, the director's family did not live in a room shared with a stranger, but enjoyed spacious and comfortable accommodation. All of this felt like something out of a fairy tale.

The living conditions of workers at the Chelyabinsk plant had been hard even before the war - many lived in basements and dugouts. With the start of the war, Chelyabinsk faced an influx of evacuees from western regions of Russia, which made conditions worse.

In December 1943 the plant's management discovered that up to three hundred workers were sleeping at the plant, on the shop floor, as they had nowhere else to go. Some said they had no winter clothes, others - no footwear. They could not leave the plant.

While people were prepared to put up with hardship during the war, when it ended, their patience wore thin. While joyous about the defeat of Nazi Germany, many in Chelyabinsk were sick of the constant humiliation of living in squalor.

The three boys heard the adults complain about damp basement accommodation, leaking roofs, soup made out of nettles, no soap in four years and many other problems. They experienced extreme poverty and felt like they had very little to lose.

They grew increasingly angry with the injustice they observed and with the contrast between what Soviet propaganda claimed life was like in a socialist country and what they could see with their own eyes.

One day in April 1946 the boys tore out a page from a school notebook and wrote:

"Comrades, workers, look around! The government had been explaining your problems with the war. But the war is over. Have your conditions improved? No! What has the government given you? Nothing! Your children are hungry, yet you are being told tales about a happy childhood. Comrades, look around and understand what's really happening!"

Initially the boys put up their flyers only at night, but within a few days they became more daring and stopped worrying about consequences. They even got a few of their classmates to help.

The much feared NKVD Soviet Security Services - which would become the KGB and now the FSB - quickly got word of the situation and before long figured out that the anti-government flyers were made by school children.

Schools faced checks of each pupil's handwriting to identify the culprits. Children across Chelyabinsk were made to write out words like "comrade" and "happy childhood".

Yevgeny Gershovich was the first to be arrested. Then Alexander Polyakov, and at the end of May 1946 - Mikhail Ulman. Their families were shocked - and terrified.

The boys faced relentless questioning by the security services, who were also trying to convict them of being Nazi sympathisers. The teens were indignant: how could devout Marxists also be Nazis?

Gershovich and Polyakov were tried in August 1946 and found guilty of spreading anti-Soviet propaganda. They were sentenced to three years in juvenile prison.

Later they remembered that horrendous time with its regular beatings and harassment by other young inmates, imprisoned for criminal offences.

Ulman was lucky - as he had not turned 14 at the time of the arrest, he escaped punishment altogether. His parents moved back to Leningrad quickly to stay away from the Chelyabinsk Security Services.

Gershovich and Polyakov also got off relatively easy as they were released at the end of 1946 with a suspended sentence.

Perhaps the boys' young age helped them escape much harsher consequences.

But it is also possible that the security services and judges were taken aback by the earnestness of the young rebels who, despite living in one of the most totalitarian regimes in history, believed that they could protest against social injustice and force the government to improve living conditions for workers.

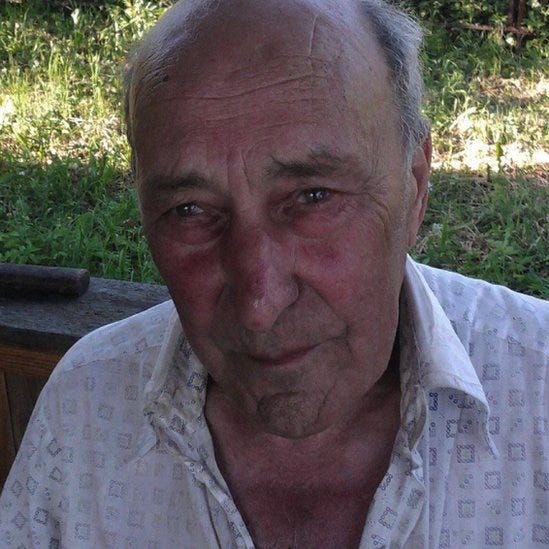

In later life both Ulman and Polyakov emigrated to Israel, where the latter still lives with his wife and where the BBC was able to speak to him.

Ulman later moved to Australia, where he died in 2021.

Yevgeny Gershovich was arrested again in the late 1940s, soon after he was expelled from university, suspected of anti-Soviet leanings.

He was sentenced to 10 years in prison but was released soon after Stalin's death, along with millions of other victims of repressions. He died in the 2010s.

English text by Kateryna Khinkulova.

Read the full story in Russian here.