Prisoners of the Caucasus? Moscow’s relationship with Baku turns sour

Following the downing of an Azerbaijani airliner late last year, the war of words has taken on a life of its own.

By Magerram Zeynalov.

Relations between Russia and Azerbaijan have sharply deteriorated since an AZAL Azerbaijan Airlines plane was shot out of the skies by, it is presumed, an Russian anti-aircraft crew.

President Ilham Aliyev made a number of harsh statements towards Moscow and Azerbaijan closed the doors of the ‘Russian House’ cultural centre. In response, Russia’s propagandists started calling for Azerbaijani citizens living and working in the country to be expelled.

Anger rises, a relationship plummets

President Putin had nothing to say when Ukrainian forces crossed the border and entered Russia’s Kursk region late last summer. Instead, he made a quick trip south to Baku, where he was welcomed at a lavish government seaside dacha.

Judging by the photos of Putin and Aliyev, looking relaxed and Aliyev’s wife Mehriban (who is also Azerbaijan’s vice-president) joining them, it was to be seen as a warm reunion of close friends.

A few months later, on December 25th, an aircraft of the Azerbaijani airline AZAL was making the journey from Baku to the Chechen capital, Grozny. When forced to attempt an emergency landing in Aktau, on the other side of the Caspian Sea in Kazakhstan, 38 people aboard, including the pilots, lost their lives. 29 survivors were recovered from the tail section of the plane.

Experts concluded that Russian jamming had caused the plane’s satellite navigation systems to fail over Grozny. It was then struck by a Russian surface-to-air missile. The incident took place when air defence crews had been in the midst of repelling an attack by drones launched from Ukraine.

Accusations of blame ensued immediately after the aircraft crashed. Russian media circulated false reports that the disaster had been caused by an oxygen tank exploding on board, or because of a collision with a flock of birds.

Ilham Aliyev reacted by accusing Russian officials of being responsible for the crash, calling for them to admit their guilt, to apologise, and to launch a thorough investigation.

Vladimir Putin got on the telephone twice to offer his apologies. The operation of air defence systems was mentioned by the Russian leader, but he carefully avoided directly blaming them for the destruction of the airliner.

Azerbaijan began suspending flights to Russian cities “for security reasons”, noting that Russian air defence crews were frequently engaged with drone attacks in the areas concerned. The media in Azerbaijan kept up their demands for an honest, international investigation of the crash.

The media goes to war

Rage in the country was exacerbated by articles in the Russian press, which were selectively drawing on transcripts of the flight’s pilots’ exchanges with air traffic controllers, assumed to have been leaked by officials in the Kazakh government.

The Russian journalists drew attention to the mention of birds by the AZAL pilots in their decision to divert to Aktau. Framing events this way was taken in Azerbaijan as an insult to the memory of the dead men, who managed to save nearly half the passengers, and an effort by Russia to dump blame for the disaster on them.

In early February, as the dispute rumbled on, the authorities in Azerbaijan decided to shutter the Russian House centre, operated by Rossotrudnichestvo, the Russian federal agency responsible for promoting Russian culture overseas – and branded in state-controlled media in Azerbaijan as “spies”.

Baku’s ambassador to Moscow was summoned to the Russian foreign ministry to listen to an official protest. The following day, his Russian counterpart in Azerbaijan was brought in to the foreign ministry in Baku to be upbraided about “reports with the character of disinformation.”

Azerbaijani media dialled up the criticism of Russia on other fronts. State-run television channel AZTV unearthed old grievances, such as the shooting of protestors in Baku in 1990 by Soviet troops, and the massacre of Azerbaijanis in 1992 in Nagorno Karabakh.

The channel also described the deployment of Russian peacekeepers to the region as a “treacherous mission,” and accused Putin himself of attempting to halt Baku during the second war in Nagorno Karabakh in 2020.

Russia’s propagandists returned fire with equal aggression. A commentator on the Tsargrad television channel spoke of Aliyev’s “extreme arrogance,” adding that the closure of the Russian House should be met with the closure of the Sadovod market in Moscow, known as a place where many Azerbaijanis work.

"One must 'befriend correctly' with such 'friends' and not let them sit on your neck,” he declared, adding that “Azerbaijani oligarchs have taken deep roots in Russian society."

The ultra-nationalist blogger Vladislav Pozdnyakov went even further, and demanded the "liquidation of the Aliyev diaspora in Russia." Their businesses should be seized, citizenship revoked, a visa regime imposed, and Azerbaijanis inside the country rounded up to fight in Ukraine.

"It’s time to respond from a position of state power, not weakness!" Pozdnyakov wrote.

The ties that bind – and their limits

There have been flare-ups in the relationship in the past. Threats to expel migrant workers, or the targeting of tomatoes from Azerbaijan in trade disputes, on one side; restricting access to Russian media and the expulsion of the bureau chief of Moscow’s Sputnik propaganda agency on the other.

Yet economic ties between the two countries run deep. The 2021 census in Russia stated that 475,000 Azerbaijanis live in Russia, while official statistics published in Baku put the trade turnover with Russia at approximately $4.8 billion last year. Moscow is Baku’s third-largest trading partner after Turkey and Italy (which is a big importer of Azerbaijani oil).

Some of the richest individuals in Russia have family roots in Azerbaijan, including Vagit Alekperov, the former head of Lukoil and, according to Forbes, the wealthiest man in the country.

The dependency is mutual, however, not a one-way street, according to economist and analyst Natig Jafarli. The North-South transport corridor linking Russia to Iran and markets further south runs through Azerbaijan.

“Without Azerbaijan, the corridor to Iran is unthinkable, and Russia is ready to invest hundreds of millions into the project," Jafarli says. "Azerbaijan is the key route for both road and rail transport, which is evident simply by looking at the number of Iranian lorries on our roads. Today, it is Russia which depends on new roads and transit corridors."

He says threats to expel Azerbaijanis would hurt Russia’s economy if acted on, noting the major manpower shortage in the country since the war in Ukraine began.

Meanwhile, Azerbaijan’s strategic alignment with Turkey is another source of resilience. Russia’s economic ties to Turkey have grown vast in recent years, and the country depends on it for tourism and agriculture, among other industries. If Russia were to target Azerbaijan, it might well find Turkey responds to protect its partner, Jafarli suggests.

The ties that bind Russia and Azerbaijan, however, are broader than economics alone.

President Aliyev is the son and heir of Heydar Aliyev, a prominent figure in the Soviet politburo, and a graduate of the prestigious Moscow State Institute of International Relations, where he was a lecturer. He met his wife Mehriban, now Azerbaijan’s vice-president, when she was a student at the Sechenov Medical Institute in the Russian capital.

Their daughter Leyla was married to Emin Agalarov, the son of billionaire real estate developer Aras Agalarov, an ethnic Azerbaijani but a Russian citizen. And the Aliyevs reportedly own two substantial properties in Moscow’s elite Rublyovka locale.

Azerbaijani is the native language of most of the country, but Russian is the lingua franca of much of its elite. Tens of thousands of ethnic Russians live in Baku. Almost every school has a Russian language department. University courses are sometimes taught in Russian, and the capital boasts a branch of Moscow State University.

Despite this, closing down Russian schools in Azerbaijan has been touted for decades by public figures, both on the government side and the opposition. After the plane crash, such calls became louder. A popular television presenter joined other voices in demanding that Russian no longer be used in public educational institutions.

For all the noise, however, muting Russian language classes is thought unlikely. Demand for education in Russian remains high, and even families who don’t speak the language compete to place their children in such schools in the hopes they may secure better paid jobs in future.

"A cultural province of Russia"

Back in the 2000s and 2010s, the appearance of Russian-speaking Azerbaijanis on television shows in the northern neighbour were a matter of pride in Baku. Quiz shows demonstrated their intelligence and comedy performances showed they were witty. For writers, meanwhile, even not very good ones, publication in Moscow was deemed a very good sign.

“In the realm of culture, we remained a province of Russia – and we have no one to blame but ourselves,” says playwright and director Ajdar Ulduz.

“Our musicians were trained in Russian institutions, where the best remained. Those that didn’t make it there left for Turkey. Only the remainder came back here,” he says. “When it comes to theatre, we depend on Russian-trained personnel. Perhaps there was no demand from our society to change this state of affairs.”

He supports the closure of the Russian House, but doesn’t see it as an attack on Russian culture itself.

“The truth is Russian culture in Azerbaijan persisted not because of, but in spite of Russia’s imperial policies," he says. "Young people are indifferent to modern Russian culture, but if you walk into any bookshop, you'll come across Azerbaijani translations of Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Dostoevsky."

"Russia is losing the region"

The Azerbaijani political scientist, Rizvan Guseynov, a researcher at the national Academy of Sciences, believes the crisis in relations is a sign that “Russia is losing the region” in the South Caucasus.

Armenia lost faith in Moscow after it failed to intervene in the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh, he points out, “leading to a deterioration in relations and squeezing Russia out of the region further.”

"Russia’s refusal to acknowledge that it downed the Azerbaijani plane, despite its dependence on Azerbaijan for logistics projects, is turning into another blow to its influence in the South Caucasus," Guseynov adds.

“Plus I don’t think Russia will be able to use force,” he says, “because the Shusha Declaration means any military attack on Azerbaijan is automatically viewed as an attack on Turkey.” The bilateral understanding was signed at a ceremony in the Azerbaijani cultural capital in June 2021 by Aliyev and President Erdogan.

What started as a media eruption has developed into a genuine crisis, according to Kirill Krivosheyev, a journalist and expert on the post-Soviet space.

"The tragedy is real, Moscow is in the wrong, but the circumstances have created a media environment, which has taken the players hostage, and has only escalated the situation," he says.

Both Russia and Azerbaijan organise their media cultures in similar ways, he points out. Officials show restraint, while there is also a Petri dish of controlled media outlets: “These were allowed to let off steam, but this has simply fuelled the conflict.”

The leaders of both nations wish to live up to their respective macho images. Krivosheyev believes that the matter could have been easily resolved.

“After the publication of the report into the causes of the AZAL plane crash, Moscow could have made concessions without losing face,” he believes. That moment may now have passed.

Read this story in Russian here.

English version edited by Christopher Booth.

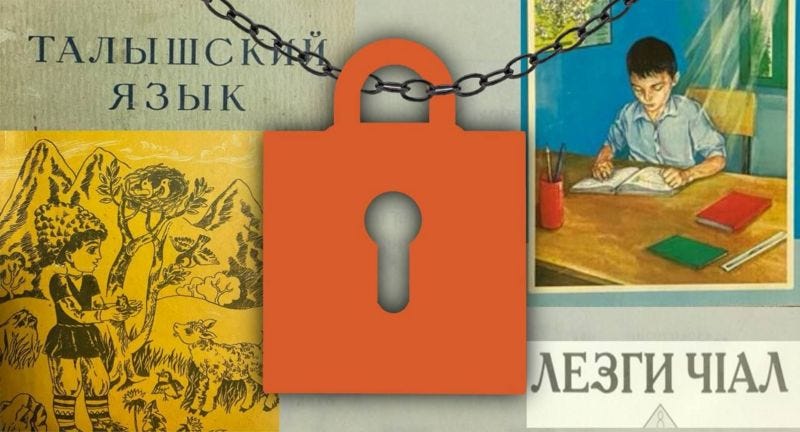

Azerbaijan’s ethnic minorities: troubled co-existence

Armenians' mass exodus from Nagorno-Karabakh put the spotlight on Azerbaijan’s decidedly mixed record of protecting the rights of some of its many other minority communities.