Dead within two weeks - how newly mobilized troops are adding to Russia’s mounting Ukraine death toll

Russian military continue to suffer losses in Ukraine, but now those who were mobilised and former prison inmates join elite forces on the casualty list.

By Olga Ivshina

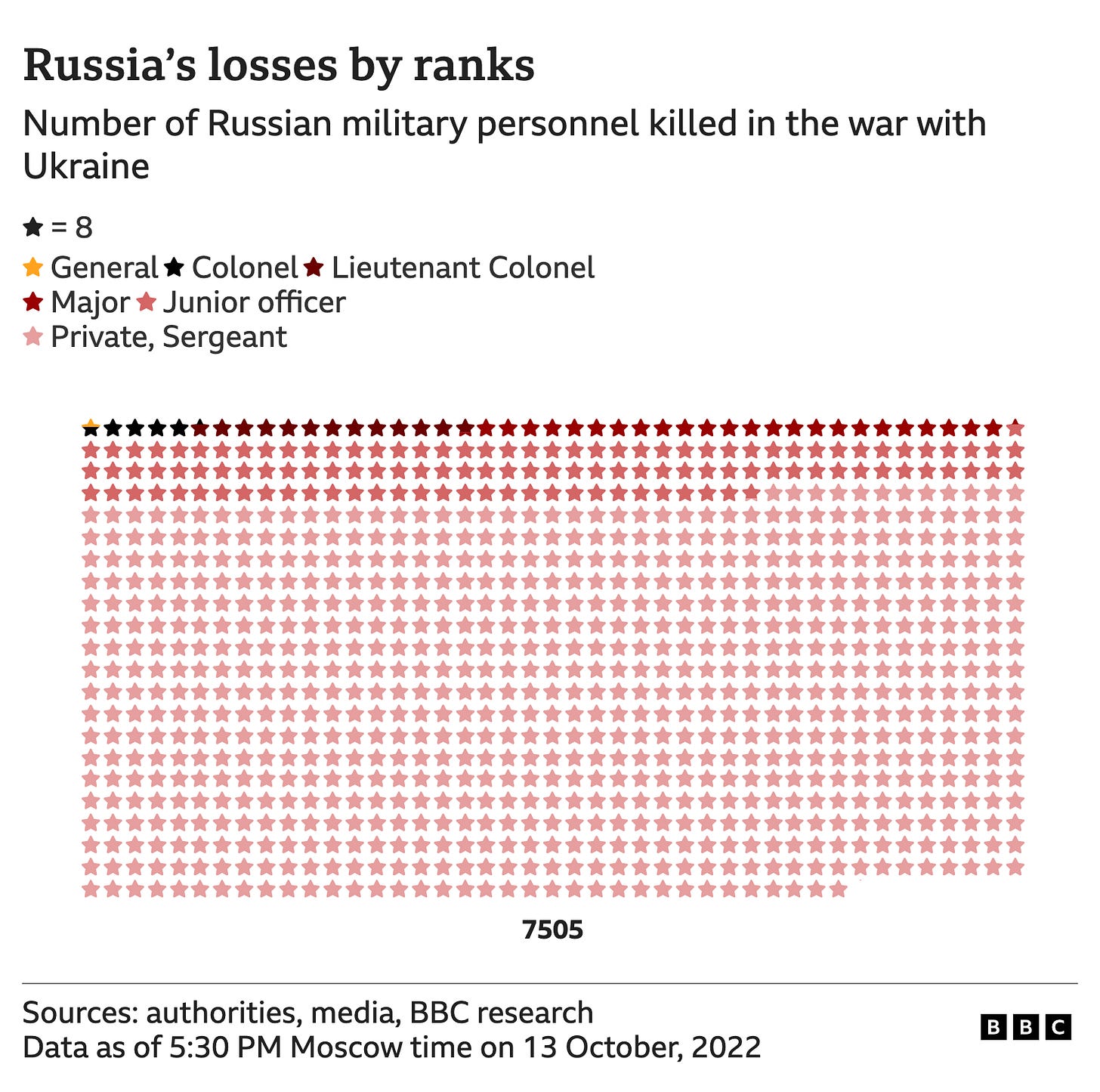

BBC Russian’s running tally of Russian casualties in Ukraine has now reached more than 7,500 confirmed deaths. In the first two weeks of October we have seen the first losses among newly mobilized soldiers, and more deaths among serving prison inmates recruited direct to the frontline. Elite units continue to suffer heavy losses, including GRU special forces troops.

Since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, BBC News Russian has been working with the Russian news website MediaZona, and a team of volunteers to compile a list of how many Russian soldiers have been killed. Our count is based on confirmed reports of deaths only and so does not reflect the full scale of losses.

By 14 October, we have been able to confirm the deaths of 7,505 soldiers and officers.

As a starting point for our count we use official death notices, issued by regional authorities and reported in the local media. We also look at posts on social media by bereaved families, and we collect information sent to us by people who have witnessed military funerals at cemeteries all over Russia.

Combat and non-combat deaths post-mobilisation

This week the Russian government confirmed the first deaths of troops called up in Vladimir Putin’s September ‘partial mobilisation’ campaign.

The authorities in Chelyabinsk region confirmed the deaths of five newly mobilised men, and open sources announced the deaths of a further 11 mobilised soldiers.

The majority of them had arrived at military recruitment offices between 25-28 September and were killed in action within just two weeks. It has emerged that the mobilised troops received no more than 7-10 days of training before being dispatched to the front line. Specialists say this would not even be enough time to reactivate the skills of people who already had combat experience.

Most of the dead were from the Urals and Siberia, but the casualties also included a lawyer from St Petersburg and a civil servant from Moscow – neither of whom had previous combat experience.

So why are newly mobilized soldiers finding themselves on the frontline with little or no retraining?

Military observers who have spoken to the BBC say as the Russian army comes under increasing pressure from Ukrainian offensives, over-stretched commanders simply do not have time to spare on training reservists, and instead throw them straight in at the deep end in dangerous areas.

The mobilization campaign has also put a spotlight on the weakness of the Russian army’s training bases, observers say. They are clearly not designed to cope with large numbers of newly mobilized troops.

There have been many videos posted on social media by new recruits complaining about everything from poor living conditions, to a lack of officers and instructors, no clear timetables for the day, and an emphasis on roll-calls and seemingly random and pointless drills instead of proper combat training.

At least 18 mobilised soldiers are reported to have died at recruitment centres or in military units before they had even been sent to the front line.

Row upon row of fresh graves

Looking at the confirmed casualty figures region by region, Dagestan still has the highest number of losses – with 319 confirmed deaths. Krasnodar Krai has now moved up to second place, with 303 people, followed by Buryatia, with 297. To give an idea of scale, we know of only 29 dead from Moscow, despite the fact that the capital’s residents make up almost 9% of Russia’s population.

As the casualties mount, Russian officials across the country are becoming more reticent about making death notices public. But there are other ways to find out about soldiers’ deaths. Memorial plaques in schools, new gravestones in cemeteries, and memorials in parks and military units all have a story to tell.

In the last month, the BBC has gathered information about new graves in cemeteries all across Russia, in the Kaliningrad and Omsk regions, in Moscow region, and in the Krasnodar and Primoski regions.

In total, since the start of the war, we have been able to confirm new graves in more than 60 cemeteries across the country, from Kaliningrad to Vladivostok.

By cross-checking the names we can see that in almost every cemetery there are many deaths which have not been publicly announced or even acknowledged by relatives on social media.

We have uncovered several examples of this in recent weeks.

In the cemetery in Medvedevka, in Kaliningrad region, there are 29 new graves in the military section – all soldiers killed since the invasion of Ukraine. Only 18 of these deaths have been officially announced.

In a cemetery in Ussuriisk, in the Far East, the number of unreported deaths is even higher. Of the 16 soldiers newly buried here, only 5 have been officially acknowledged or mentioned on social media.

Military casualties by rank

Based on the deaths the BBC has been able to confirm, a picture continues to emerge of heavy losses among special forces and in the officer corps.

Of the 7,505 confirmed names on our list up to 14 October, more than 2200 were elite troops: soldiers and officers from special forces units, marines and air force pilots.

In just one operation, during the retreat from Lyman in late September, as BBC Russian discovered, an entire squad of nine GRU 3rd brigade elite special forces troops from Togliatti were killed.

According to our numbers, over the past eight months since the start of the Russian invasion, 17 per cent of all confirmed Russian military deaths in Ukraine are officers – that’s 1,278 people.

The highest death toll has been among junior officers. Many more have been killed than their subordinates.

Even before the start of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the Russian army had problems with understaffing. According to military specialists, Russia started the war with an abundance of military equipment but a severe shortage of trained personnel.

As a result, commanders ended up having to command soldiers in combat in place of a sergeant, and personally leading them into battle, or holding a defensive line with them, instead of directing the military action through their subordinates.

Moreover, many junior officers are still quite young (most who gain the rank of lieutenant are only 21-22 years old) and inexperienced, and yet are already responsible for making decisions about how to fulfil the objectives set for them by the commanders.

Deaths by unit

As the war enters its ninth month, the heaviest losses - at 21% - have been among the infantry.

Airborne troops make up 16% of all confirmed deaths, although this is down from 20 per cent in August. It’s clear from open source information that many airborne sub-divisions have suffered high numbers of deaths and injuries, meaning they are no longer able to participate in frontline operations on the same scale as before.

One reason official military casualties in some areas are falling, is the bigger role ’volunteer fighters’ and private military companies like the Wagner group, are now playing in frontline fighting. and

As the BBC has reported previously, there’s a particularly high attrition rate among ‘volunteers’. These are people who sign up on short-term contracts, often lasting no more than a few months. They often get between three and 10 days training before being despatched to the frontline.

In early July the first reports began to emerge of prison inmates being recruited to fight in Ukraine in return for a reduction in their sentences. The MediaZona news site estimates that at least 480 prisoners have joined up so far.

As of 14th October, the BBC has been able to confirm the deaths of at least 16 former prisoners in Ukraine.

Just how many deaths might there have been in total?

The BBC’s casualty list contains details only of deaths which we have been able to confirm independently. It is not a comprehensive list.

As we know from information shared with us about new military graves in cemeteries, many deaths are not publicly announced or acknowledged.

By comparing the number of new military graves, with the official information publicly available about casualties, we estimate that our confirmed casualty list is likely to contain between 40 and 60 per cent fewer names than the actual overall death toll.

On that basis, working with our confirmed deaths, a conservative estimate of how many people the Russian army and National Guard have actually lost so far, could be around 15,000 people.

Michael Kofman, an expert on the Russian military from the US-based Center for Naval Analyses (CNA), says for every Russian soldier killed in Ukraine, on average 3.5 are wounded. So again, working on the basis of our confirmed death toll so far, it’s possible that we could be looking at an overall figure of dead, injured and missing in action of at least 53,000.

According to British intelligence estimates, the number of Russian soldiers killed in Ukraine by September, stands at 25,000.

Ukraine’s General Staff puts that number at 60,000.

It’s also difficult to establish how many people have been killed fighting with the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk ‘peoples’ militia’ forces.

As of 7 October, the authorities of the self-proclaimed DPR has admitted to losing 3,285 soldiers.

The self-proclaimed LPR does not give out official casualty figures, but judging by open source information losses are in the hundreds at the very least.

The BBC has seen over 4,000 messages and posts in social media groups for supporters of the DPR and LPR, made by people searching for male relatives, conscripted into the “people’s militia” forces, and not heard from since.

On 21 September, after a long silence on casualty figures, the Russian Defence Ministry announced that 5,937 soldiers had been killed in Ukraine.

At that point, the BBC already confirmed the deaths of at least 6,200 service personnel.

Read this story in Russian here.

Translated by Elsa Haughton.