‘Made with hate’: Why Russian teenagers are joining neo-Nazi groups

Researchers report a spike in far-right violence this year, but say many self-styled neo-Nazis seem more motivated by social media hype than ideology.

By Amalia Zatari.

Late last year, in the historic Russian city of Kostroma, a teenager was shot in the face with a flare gun on his way home from a film screening about a left-wing activist.

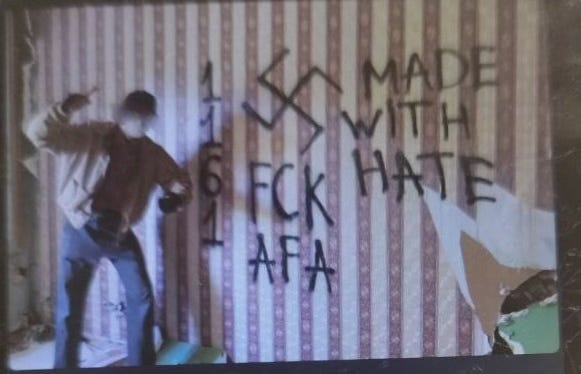

The attack was allegedly carried out by a member of a local neo-Nazi group called Made With Hate - in a violent and politically-charged act that symbolised a growing trend across Russia.

Despite the Kremlin’s repeated justification for its full-scale invasion of Ukraine as a battle against "Nazism," there has been a sharp increase in neo-Nazi violence within Russia itself. According to the Sova Centre, an organisation that monitors hate crimes, far-right attacks in Russia more than doubled in 2023 compared to the previous year.

This new wave of extremism harks back to the 1990s and early 2000s, though it has yet to match the murderous brutality of that chaotic period following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

But now the violence is fuelled by online platforms like Telegram and TikTok, where mainly young Russians encounter and amplify far-right ideology in digital spaces often beyond the reach of law enforcement.

Spraying swastikas

In Kostroma, a city of some 264,000 people on the Volga river, a group of teenage boys began communicating via a channel on the Telegram messaging service in early 2024.

Initially the chat was focused on organising trips to football matches or casual meet-ups. But soon things took a darker turn.

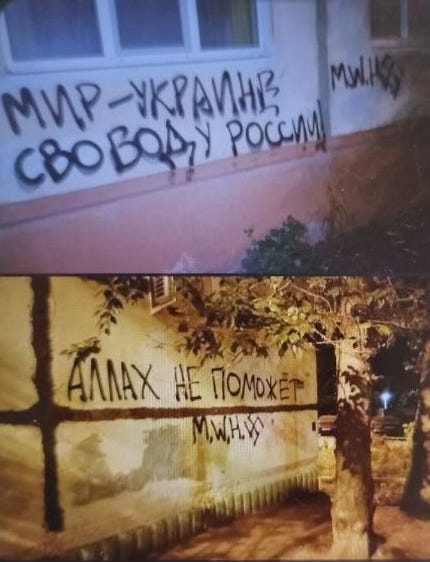

The group started tagging graffiti of swastikas, Celtic crosses, and other far-right symbols around the city, according to former member “Anton”, who was 17 at the time and spoke to the BBC on condition that his real name not be used. The teenagers dubbed their gang Made with Hate and would also spray those words on walls.

By the summer of last year, the teenagers had moved onto physical violence.

“They’d get together and all of them would beat someone up,” said Anton, who used “they” rather than “we” while talking with the BBC in an attempt to distance himself from the group.

“They’d go around, looking for drug addicts and alcoholics, and jump them. They were always on the hunt to get people from left-wing movements,” he added.

The attacks were often filmed and posted on the Telegram channel, which by that time had more than a hundred members. These came not only from Kostroma but also from other Russian cities and in some cases - according to Anton - even Ukraine and Poland.

Members of the channel were united by their far-right views, though they were radicalised to different degrees.

Anton said: “There were nationalists, and then there were straight-up Nazis. There were casuals, too: people who just wanted to fight. They’d come out with the group, they’d be the first to get involved.”

Loss of an eye

The young man who was attacked on his way out of a film screening was Yaroslav, a 17-year-old who had moved from Moscow to Kostroma to study jewellery making.

In November 2024, he and a friend had gone to watch a documentary about the murdered anti-fascist Ivan Khutorskoy, organised to commemorate the 15th anniversary of the latter’s death at the hands of neo-Nazis.

When Yaroslav left the screening, he was approached by nine people who started interrogating him about his political views, according to Antifa.ru, a Telegram channel for the anti-fascist movement in Russia.

One of them pulled out a flare gun and shot him in the face.

The attackers scattered and Yaroslav’s friend called an ambulance, but doctors at a nearby hospital were unable to save one of the teenager’s eyes. Yaroslav was forced to abandon his studies and return to live with his parents near Moscow. He declined to speak to the BBC.

Two days after the incident, the alleged attacker, also 17, was detained and now faces more than a decade in prison, on charges of hooliganism and causing serious bodily harm with the use of a weapon.

While Russian law forbids the identification of minors involved in legal cases, the Kostroma court at one point accidentally published the full name of the suspect, which the BBC will not report.

Anton said that the teenager was a member of the Made with Hate Group and had joined just weeks before his arrest. The suspect’s father and lawyer declined to comment on the case to the BBC.

A teenager who went by the nickname Buchenwald - after the Nazi concentration camp - was also later arrested in connection to the attack. Anton said that Buchenwald, 17, was a leading figure in the neo-Nazi gang, despite being Buryat, a member of an ethnic group indigenous to eastern Siberia, rather than Slavic.

Both suspects remain in pretrial detention. The BBC contacted the local investigative committee for further updates on the cases, but at the time of publication had received no response.

A broader trend

Anton told the BBC that he left Made with Hate last October, before the attack on Yaroslav, after gaining “a deeper understanding” of neo-Nazism.

“I didn’t know much about anything back then, I hadn’t read anything, so I didn’t even know what views I held,” he said.

“I realised that they [members of the group] didn’t know s*** themselves, just the most superficial rubbish. And I’m not like that.”

The security services briefly detained Anton last December, seizing his computer and phone, and questioning him as part of their investigation into the creation of the extremist group.

While the Russian media focused on the events in Kostroma, they are part of a broader trend.

In 2023, the most recent year for which figures are available, the Sova Centre - which is itself recognised as a “foreign agent” in the country - recorded 259 far-right attacks in Russia, one of which was fatal.

This is more than twice the number from the year before, after a decline over the previous ten years. Many of the perpetrators were under 16, while victims included people of non-Slavic appearance, the homeless, and ideological opponents.

Legal data collated by the Sova Centre bears out this trend: in the first four months of 2025 alone, eight criminal cases involving 15 people have been opened for hate crimes. That compares to 18 cases involving 57 people across the whole of the previous year.

Meanwhile, there were 18 cases against 29 people in 2024, and 11 cases against 15 people in 2022.

The new neo-Nazi groups, the researchers said, were trying to revive "traditions and all the types of violence developed in the 2000s."

The form of the attacks echo those of earlier neo-Nazi gangs, such as “fake dates”, in which gang members set-up meetings with gay men and those they considered “paedophiles” in order to assault them.

They also include “white wagons” - coordinated attacks on passengers in trains - and “peeplkhheiterism”, which translates as people-hating and is based on the belief that society should be purged of both ordinary people and supposedly “undesirable elements”.

Xenophobic officials

According to Sova researcher Vera Alperovitch, today’s neo-Nazi teens are driven more by a desire for online attention than ideology. “The thirst for ‘hype’ plays a greater role now than ever before,” she said.

In the far-right circles of the 2000s there were many people who "just liked to hit someone," she said, but the core of the movement then were ideological neo-Nazis: "savvy people who read neo-Nazi literature and published their own magazines.”

Now the activity of Nazi skinheads in Russia is on the rise again, but this subculture is still in its infancy and has not yet been politically and ideologically formalised, she said.

"These are not ideological fighters like before. Putin, the war, America - it's all too complicated for them,” Alperovitch told the BBC. “[There’s just the idea that] there are migrants - we should beat them up and make a video."

The far-right movement in Russia has been gradually reviving since the 2010s, Alperovitch added.

This rise has been fuelled by xenophobic rhetoric from Russian officials and state media, as well as "the general militaristic bias of Russian society,” she said. Alperovitch pointed to a right-wing turn in the political agenda, not only in Russia but also abroad - for example, the popularity of European right-wing populists or Donald Trump in the United States.

"The escalation of violence [among Russian extremists] is happening literally in front of our eyes," she added, but remains below the levels seen in the 1990s and 2000s “so far”.

TikTok, Telegram, and ‘Tesak’

Social media has become the main gateway to radicalisation. Telegram channels like “Rural Club ‘Hands Up!’”, with over 22,000 subscribers, regularly share videos of attacks, fundraisers for arrested members, and even birthday tributes to Adolf Hitler.

The channel also shares videos describing how best to carry out attacks and hide from CCTV cameras.

TikTok, too, is flooded with far-right content. Young users post tributes to infamous Russian neo-Nazis like Dmitry Borovikov, Alexei Voevodin, and Maxim "Tesak" Martsinkevich – the latter a convicted extremist who died in custody in 2020, sparking a surge of interest in right-wing activism.

Borovikov was killed by police as he tried to resist arrest in 2006, while Voevodin is serving a life sentence for his involvement in a spate of hate killings.

"From time to time we learn from chat rooms and channels of the ultra-right that a criminal case has been opened against this or that activist, or even a group of activists, and that they have been detained," said Alperovich.

"But law enforcement does not advertise this in the media, apparently trying not to draw attention to the fact that there are neo-Nazis in Russia. The Russian authorities, on the other hand, tell us that they exist only in Ukraine."

The approach of various neo-Nazi groups to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine appears confused.

While Made With Hate would tag anti-war slogans around Kostroma, teenagers from the gang would patrol the city with adults from the local cell of the notorious Russian National Unity Group (RNU), which supports the invasion and holds rallies in praise of Russian soldiers. Some members of the RNU have been fighting in Eastern Ukraine since 2014.

Global scope

The rise of extremist violence is not only a Russian phenomenon. Paul Jackson, a professor at the University of Northampton, said poorly moderated platforms like Telegram have given the global far-right a “new and potent dynamic.”

Jackson added: “Young people sometimes feel a lack of purpose in society and find answers to their frustrations in extremist content. Often for young men, themes of hypermasculinity underpin these feelings.

“Moreover, people can find a sense of community in these extremist spaces they are not finding elsewhere.”

Graham Macklin, a researcher at the University of Oslo, said that the average age of perpetrators is falling: the youngest person arrested for far-right terrorism in the UK was just 13 at the time.

“The digital milieu [has] a unique visual aesthetic which no doubt enhances the appeal of these environments for those looking for extreme or ‘edgy’ content,” Macklin said.

Back in Kostroma, Anton said that the movement continues to grow despite the criminal cases.

"Literally in the last two months so many new guys have appeared. I walk down the street and don't recognise anyone," he said. “A year ago there were 15 people in the right-wing movement, including me, and now there are probably 40-50 people,” most of them teenagers.

Yegor, an anti-fascist activist in the city who declined to give his last name, said it had become “fashionable and cool” to join such far-right gangs.

“They want to fit in, to create a tough guy image for themselves.”

But Anton’s defection from Made with Hate, and subsequent communication with Yegor in what they both described as a small city where everyone knows everyone, offered a faint glimmer of hope. At the beginning of this year, anti-fascist activists even went so far as to invite Anton to a concert in a nearby town.

“They were cool guys,” Anton said, remembering the event. “It’s actually a funny situation. In the summer we were beating each other up, and in winter we were standing together, dancing at a punk concert."

Since then, Anton has signed up to fight for Russia in the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, though when he spoke with the BBC his reasons for doing so seemed unclear. “Basically only because my dad was a soldier”, he said, explaining that his late father had previously served in Chechnya.

“I didn’t sign up to defend anyone’s ideas,” he said. “I’ve always been for extreme. If I’m killed, I’m killed.”

Read this story in Russian here.

English version edited by Theo Merz.

Additional reporting by BBC News Russian Investigations Team.

"We are Russians: God is with us." The new far-right in Russia — and why the Kremlin lets it flourish

BBC Russian looks at how today’s Russian nationalists differ from the far-right movements of the recent past – and why this time they have not been crushed by the state.

I'd draw your attention to Sky TVs series Ross Kemp's Extreme World...Ukraine broadcast in 2015 it was due to be shown again last year but strangely that never happened. The program begins by witnessing a torch light parade in Kyiv and we are talking thousands of participents in that event. If you search you can still find the full video on the net.

Furthermore I'd add an article from ABC News Australia...

Ukraine crisis: Inside the Mariupol base of the controversial Azov battalion" 2015

"The first thing you notice as you walk through the corridors of the Azov battalion's base in Mariupol are the swastikas.

There are many — painted on doors, adorning the walls and chalked onto the blackboards of this former school, now temporary headquarters for the Azov troops....... "

regards

When I attended my first 'Political History' lesson way back when, the teacher sat down and asked the class a question.

"What is Left Wing and Right Wing".

Us pupils mumbled replies the teacher stood up and said "Left Wing is the State is all important and Right Wing the Individual is all important."

When our politicians and their mouthpieces talk of "The Right" the definition is Right Wing bad. They tell us the Nazis are Right Wing, but thats a nonsense the Nazis were socialists the clue is in the official name of Nazi Party, the National Socialist German Workers' Party. The Nazi state was all important.

The State being all important wants, indeed needs, to quash the individual, the Right. However that need not mean all States are bad.