Rewriting history – the planned new school textbook accused of whitewashing Russia's imperial past

Russian school students are about to get another new history book, this time reframing their country's 19th century past and arguing Russia was never a colonial power. Many of its neighbours disagree.

By Anastasia Golubeva.

From next year Russian schoolchildren will start using a new textbook on 18th-20th century history. According to the author, historian Aleksandr Chubaryan, it will tell them that Russia was not a colonial power and did not have an empire in the way that Britain, for example did. His pre-publication comments have sparked much controversy. BBC Russian asks historians from states and regions that were formerly part of the Russian and Soviet empires for their reaction.

“All the world’s empires had overseas territories, but we shared a common space. So when they became part of Russia they were included in the same economic area, and were united as a single whole.”

Historian Aleksandr Chubaryan outlines the controversial idea behind his new text book for Russian high school students.

Countries which were once part of the Russian empire and the USSR may see Russia as a colonial power, he argues, but Russia’s empire was different. It wasn’t a case of “classical colonialism,” he argues, and any comparisons with the British empire are just plain wrong.

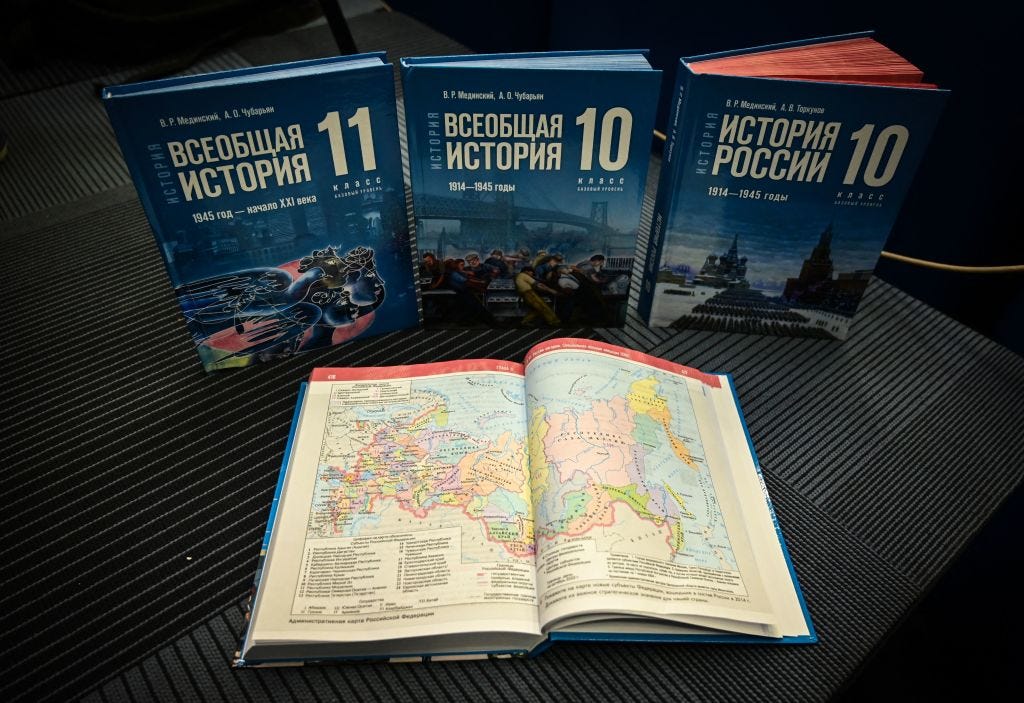

Chubaryan’s new book, which will cover 18th-20th Russian history, is due to roll out in 2024. And it’s not the only new school book attempting to reassess Russia’s past.

Former culture minister, and presidential special advisor, Vladimir Medinsky, has just published a history of the USSR and Russo-American relations, helpfully including an extra chapter explaining to school children how to understand the “special military operation” aka Putin’s war in Ukraine.

Medinsky’s textbook paints an upbeat picture of the way the Soviet Union operated, claiming the 15 constituent republics worked together for the common good, that interethnic marriages “wove together” people from different national groups, and that xenophobia was absent. Any nationalist, separatist or anti-communist sentiment was driven solely by the US and the CIA, Medinsky maintains.

BBC Russian asked historians and decolonisation experts from neighbouring countries that were once part of the Soviet and Russian empires, for their reactions to Russia’s latest attempts to reassess the past.

BBC is blocked in Russia. We’ve attached the story in Russian as a pdf file for readers there.

“Still a classical empire”

For Serhii Plokhy, professor of Ukrainian history at Harvard University, the idea that Russia’s empire was somehow different because it didn’t involve overseas territory is “doubtful at best.”

“Russia was a classic land empire, like the Mongols, the Hapsburgs, and to an extent, the Ottomans,” he told the BBC.

Exiled Azerbaijani historian Arif Yunusov, from the Institute for Peace and Democracy agrees with that assessment.

“One of Russia’s great hobbies, is comparing itself to Great Britain,” he told the BBC. “But there were other empires without overseas territories, like the Ottomans – and you don’t see Turkey describing “conquests” as “annexations.” There are plenty of parallels between Russia and Turkey – an accumulation of conquered peoples and territories around a centre.”

For Yunusov there’s a striking difference between the language and ideas in the new Russian textbooks and the way the history of Russia’s conquest of the Caucasus was described in Russian 19th century books and documents.

“They called the locals “natives,” and described what had to be done to conquer them,” he says. “Very different terminology from today’s.”

For Tuvan activist and podcast host Danhaya Khovalyg, even the idea of framing the question around how an empire conquered someone else’s territory is “colonial and western-centric.“

“I’m defining colonisation as 'the process of establishing dictatorship and influence – economic, political, and cultural – by one territory over another, with one dominant colonising culture and ideology,” she says. “In this sense, Russia is the most classical empire of them all.”

Internal colonisation

Back in the 19th century, the way in which Tsarist Russia gradually expanded the borders of its empire into surrounding territories was dubbed “internal colonisation.”

The term was first recorded in 1895 in the Brockhaus Encyclopaedia, says historian Dr Dina Gusejnova of the London School of Economics.

“It’s an analytical term, describing how an empire’s borders would advance by ‘voluntary colonialism’ backed by state power,” she explains.

“The majority of the population were exploited by a small elite. International observers were already writing about this back in the 19th century, as were the Russian socialists of the imperial period.”

The modus operandi for the expansion of the Russian empire was actually not very different from the way Britain or France increased their territory overseas, says Stephen Badalyan Riegg, a historian of the Caucasus from the University of Texas.

“The international community of historians – including ethnic Russians from Russia – generally agrees that the Romanov empire used the ideology and practises of ‘settler colonialism’ not dissimilar to those of maritime empires.”

But whether by land or sea, the key thing all expanding empires had in common was the way they established a hierarchy, he says.

“All empires are entities that place one group above another – it’s not just the cosmopolitan elite, but entire linguistic, religious and ethnic communities that are elevated.”

So is Chubaryan right that Russia’s empire was somehow different and better than others?

“The Russian empire was no better or worse than its contemporaries,” says Riegg. “It fought – and cooperated with – Britain, Japan and the other powers, and saw itself and its rivals as actors in a common global competition for the resource of foreign peoples and lands.”

A shared space?

For Armenian historian Tigran Zakaryan another contentious argument in Chubaryan’s new book is the claim that Russia incorporated conquered territories into a shared “socio-economic space.”

“Before it was colonised, America had zero economic ties with European states. Afterwards, the European states integrated it completely into their own systems,” he says.

“Pre-colonial India actively traded with Britain – it was only after the Imperial takeover that the British began to dominate the Indian economy. I don’t see why we can’t look at the various regions that were part of the Russian empire through the same lens,” he adds.

Zakaryan also argues that the concept of a “shared economic space” implies that territories that have been forcibly incorporated into an empire were somehow ‘backward’ prior to that. It’s an argument that resonates with many historians in the Caucasus and Central Asia.

The Soviet era - “developed empire” and “backward periphery”

At the beginning of the last century, the Russian Empire found itself in chaos following two revolutions and the aspirations of conquered nations to achieve their independence, says Kyrgyz historian Eleri Bitikçi.

The Bolsheviks managed to save Russia from further disintegration, and Soviet Russia was able to retain control over the countries of Central Asia through concessions in its national policies in the early 1920s. However, the situation changed in the 1930s, when Moscow returned to glorifying the Russian people and began a policy of Russification of national peripheries.

“This shift was connected to the proclamation of the Russian people as the most advanced in the world, having been the first to carry out a communist revolution and being placed above other Marxist formations, including Western European states,” he says.

Colonization of the Central Asian countries did not cease. But this time, it was industrial colonization. A new hierarchy emerged in the USSR, with the more proletarian population considered more developed. This formed the basis for new colonial relationships between Moscow and the Central Asian countries. The greatest industrial colonization was imposed on Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, where local cadres were trained for agriculture. The core essence of colonial relationships – the "developed empire" and the "backward periphery" – remained unchanged even within the USSR.

“During Soviet times in the Kirghiz Soviet Socialist Republic (now Kyrgyzstan), technical specialities were not taught in the Kyrgyz language, whereas humanities, like pedagogy, history, linguistics, and agricultural specialities were taught in Kyrgyz. As a result, there was a shortage among Kyrgyz people of highly qualified specialists in the industrial sector. For example, in the late 1980s, on four factories in the capital (Frunze, now Bishkek), only 2.8% of Kyrgyz workers had high qualifications, while 49.3% had low or no qualifications,” Bitikçi says.

Whitewash and erase: how to write a Russian history textbook

So how did Soviet era textbooks deal with Russia’s colonial past and the formation of the USSR?

“In the [former] republics, we were told what we could and couldn’t write,” says Arif Yunusov. “There was a framework. We couldn’t criticise Russia, we had to talk about Azerbaijan’s voluntary accession – and we had to say that Russia was on a historic mission to make life better. Back then, everything bad was the fault of “bourgeois” states.”

Yunusov remembers that historians couldn’t write about the Qu’ran, because of the Soviet Union’s anti-religious ideology, and the KGB blocking access to archives.

The textbook on the history of the USSR was a textbook on the history of Russia, scarcely touching on the histories of the republics at all, Yunusov says. And historians who tried to criticise this narrative were labelled nationalists.

Viewed through this perspective, Chubaryan and Medinsky’s textbooks are actually nothing new, says Tuvan activist Danhaya Khovalyg.

The state has long published biased textbooks on the histories of the peoples it colonised she adds.

“Next year a new textbook is coming out, putting more emphasis on the ‘fraternal ties’ between the Tuvan and Russian people.”

“Russia has been rewriting history for centuries, particularly colonial history – but it’s only now that their own history is being rewritten that some Russians are starting to pay attention,” Khovalyg adds.

Reframing the empire

It’s clear both from the new textbook and from recent public pronouncements by Russian officials, that they are well aware of the wider global debate about the impact of colonialism and empire, and that they are seeking to exploit it.

“The Russian state is erasing the word ‘empire’ because it is now associated with hierarchies, exploitation and marginalisation,” says Stephen Riegg. “Hence Chubaryan repeating the official line – the imperial and Soviet empires were more humane and egalitarian than their western counterparts.”

But Chubaryan’s approach fails to take into account any insights from specialists in countries which were formerly Soviet republics. And for Tigran Zakaryan that makes the arguments “pseudo-anti-imperialist.”

Like Germany in the build up to the First World War, Russia is trying to put itself on the side of those fighting against colonisation, and the only way it can do this is to totally whitewash or deny, its own colonial past, he says.

History – a list of excuses for war

It might be 2023, but the version of history now being dished up to Russia’s schoolchildren seems to be a mash up of the Stalinism and early 20th century Russian conservative thought, says Tigran Zakaryan.

And for Russia’s neighbours, and also for some parts of the Russian Federation that’s something that feels increasingly uncomfortable.

“This apologia for empire – which stops short of saying the word – is Russia’s intellectual justification for its obsession with reclaiming the republics,” says Zakaryan.

Dina Gusejnova of the London School of Economics agrees. She notes that new textbooks aimed at Russian 11th graders “explain the inevitability – and even necessity – of war against a neighbouring state.”

“Of course, Russian nationalism is ‘good’ now, so Ukrainian nationalism has been relabelled ‘ultra-nationalism’,” she says. “The struggle of Russian forces against Ukrainian ‘ultra-nationalists’ is compared to the anti-fascist struggle of the Second World War – but the Ukrainians who fought on the Soviet side have somehow disappeared, only the ‘Banderite’ extremists remain.”

Chubaryan’s new textbook will detail "the long version" of Russian history, as opposed to Putin’s summary of the 20th century, “from Banderites to ultranationalists."

“Essentially, this will be a study of a ‘good’ empire without imperialism and colonialism, showing the continuity of the Russian Empire, the multinational USSR, and the Russian Federation. And that gives the authors the opportunity to say the post-Soviet space doesn’t have the problems of decolonisation faced by empires that ended – take France, and the Algerian war,” says Gusejnova.

Danhaya Khovalyg describes this approach to history as the “agony” of an imperial regime in its death throes.

"The authorities know people are starting to talk about colonisation and decolonisation,” she says. “All they can do now is throw those words around, in the hope of convincing the younger generation, and strengthening the loyalty of people who already support the regime."

She claims the Kremlin now fears the label “Russian empire” due to Ukrainian activists and others who describe Russia’s aggression as a “colonial war.”

“Textbooks would have you believe that war is not Russia’s evil,” says Azerbaijani historian Arif Yunusov. “Russia leads crusades of liberation; it does not conquer. The British may seize Afghanistan or India, but Russia merely annexes, it unifies. And Moscow doesn’t care what people think in the former republics. The important thing is for the Russian people to swallow the myth – because the story of Russia is a story of constant war.”

Read this story in Russian here.

Translated by Pippa Crawford.

Additional reporting by Aisymbat Tokoeva.

Edited by Jenny Norton.