Polish ghosts and Ukrainian heroes

Why disputes over the mass killings of Polish civilians during World War Two continue to overshadow relations between Ukraine and Poland.

By Tim Whewell for BBC News Russian.

In January 2025 ahead of Volodymyr Zelensky’s official visit to Poland, Kyiv and Warsaw announced a timetable to restart long-awaited work to investigate one of the darkest episodes in Polish and Ukrainian history. The mass killings of Polish civilians by Ukrainian nationalist partisans, in the Volhynia and Galicia regions during the Second World War, and the subsequent retaliatory murders of Ukrainians, have long haunted both countries. Three years on from Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Poland is one of Ukraine’s closest allies, but bitter disputes over how to deal with the ghosts of the past, have threatened to derail relations between the two.

“Ten metres to our left was the school. And over there was the church and the organ player’s house..”

I look where Polish historian Leon Popek is pointing. But there’s only a vast, empty, freshly-ploughed field. All that remains of the Polish village of Ostrowki is a lilac bush planted before the Second World War, stunted by the wind - and, at its foot, a headless, armless statue of the Virgin Mary that once stood in the church.

“Everything was destroyed within just a few hours on August 30th, 1943, by the Ukrainian Insurgent Army,” Popek says. “They enter each home. They drag out or chase out the people and take everyone to the school building .. men, women, children.”

Then they were led out, ten at a time, to a nearby farmyard. “In the middle there is a hole in the ground. They put them down, and kill them all with axes.”

Popek calculates that at least 474 Poles were murdered in Ostrowki, including 204 children. Among the victims were his grandfather, and other relatives.

“I remember hearing these stories since I was very, very little. How my grandfather died. How my aunt died. And her children. And her husband. Over 30 people. My family, they would get together and they would talk about it. And why it had happened. Why and why and why”

The same question has been asked for the last 80 years in the many Polish families that originated from the region of Volhynia. Before the Second World War it was part of Poland – though the population was largely Ukrainian.

Then it was conquered in 1939 by the Soviet Union, and in 1941 by Nazi Germany. The underground Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA) was formed in 1942 as the military wing of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) – a militant, far-right movement engaged since 1929 in a violent campaign against Polish targets to try to establish an independent Ukrainian state.

In the Second World War, Poland, the Soviet Union, and Germany were all regarded as enemies by the OUN. Stepan Bandera, leader of the more radical of its two factions, was imprisoned by Germany for most of the war. But at various times, the OUN tried to negotiate with the Nazi occupiers and some OUN/UPA fighters participated in the killings of Jews.

However it was Polish civilians who were to bear the brunt of the violence unleashed by the UPA.

No-one knows the exact number of Polish victims, and estimates vary. Poland’s state-funded Institute of National Memory says Polish researchers “cautiously” estimate that about 100,000 Poles were killed by Ukrainians between 1942 and 1945 in Volhynia and the neighbouring region of eastern Galicia, now also in Ukraine, and areas within present-day Poland.

The Ukrainian historian Serhiy Plokhy, director of the Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard University, gives a slightly lower estimate of 60,000 – 90,000 Polish victims.

Most were killed not with bullets but with sadistic brutality, using axes, hammers and knives, or burnt alive.

The number of Ukrainians killed by Poles in self-defence or retaliation has been estimated at between 10,000 and 15,000.

But some Ukrainians were also killed by fellow Ukrainians, because they were accused of sympathising with Poles. Outside the roofless ruins of a huge red-brick Catholic church in the village of Kysylyn, I meet 86 year-old Lyudmila Hirska. She bursts into tears, remembering how the Polish neighbours she grew up with were murdered at mass on 11th July 1943.

Her family was Ukrainian. But the killers came to her grandparents’ house too.

“They said: ‘We came to shoot you. Because of the Poles, because you are friends with Poles. And bang! – that was the end of grandpa and grandma. There was no sleep those nights. Only crying and crying - and that’s how they tried to build Ukraine. What was the sense in that? But that’s what Banderites were like.”

After the war, Polish survivors moved into the new Polish state, whose borders were much further west. They kept the memory of the massacre alive in their families. But more generally, it was widely forgotten amid all the other atrocities of the Second World War. And Soviet history books largely ignored Polish and Jewish victims. They concentrated on the UPA’s fight against Soviet power – which continued into the 1950s – and condemned Ukrainian nationalists as Nazi collaborators.

It was only in the early 1990s, when the Soviet Union was collapsing, that Polish historians such as Leon Popek were able to begin to investigate the sites of the killings and exhume bodies. Leon Popek eventually found his grandfather. But the process was made even more distressing by the hostility of some Ukrainian archaeologists and historians. Popek was accused of tampering with the remains of children. “They took those little tiny bones and they said that I had deliberately broken them into three parts, to increase the number of the dead.”

Ukrainian opposition to investigating the killings gradually grew. And partly, that had nothing to do with relations with Poland. It was because of Ukraine’s intensifying conflict with Russia - a conflict in which Poland and Ukraine are close allies. In 2014, when the pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych was overthrown after huge protests on Maidan square in Kyiv, more and more Ukrainians began to regard the OUN and its most famous leaders, Stepan Bandera and Roman Shukhevych, as heroes to emulate – because of their anti-Soviet, anti-Russian, credentials.

In recent years, and especially after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine, surveys suggest, positive attitudes towards the UPA and OUN have increased sharply – even in southern and eastern areas of Ukraine where most people were previously critical of “Banderites.”

And that’s due partly to the efforts of Ukrainian historian Volodymyr Viatrovych. From 2014 until 2019 he headed Ukraine’s Institute of National Memory, helping to mould Ukrainians’ view of their past. In his view, there was no“Volhynian massacre” in 1943, only a mutual bloodletting, a “Volhynian tragedy”.

“In my opinion it was a Polish-Ukrainian war,” he says. “This war was started by underground movements from both sides, Ukrainian and Polish. But very often it ended up as kind of civilian war between different villages, different ethnic groups.”

Viatrovych, who has researched the subject for many years, says Ukrainian peasants often spontaneously attacked Polish neighbours, after years of being treated as underdogs under Polish rule. He says the UPA never directly ordered the killing of Poles.

And he gives very different estimates for the death toll to those of other specialists in the subject. He suggests about 50,000 Poles were killed – and quotes research by the Catholic University of Lviv that says as many as 30,000 Ukrainians may have been killed by Poles.

Viatrovych has been accused by many Western historians of whitewashing war criminals. But he insists they are “repeating Russian propaganda” and even claims some are paid by the Kremlin.

He says: “There are no documents stating that the UPA was fighting for an ethnically clean Ukrainian state.”

Ethnic cleansing wasn’t the official policy of Bandera’s organisation. But a policy document published in May 1941 entitled “Struggle and Activities of the OUN(b) in Times of War” – edited by OUN leaders including Bandera and Shukhevych includes a section on “cleansing the land from hostile elements”. Below this heading, it says: “During the chaos and confusion it is possible to permit ourselves to liquidate undesired Polish, Muscovite and Jewish activists, especially adherents of Bolshevik-Muscovite imperialism.”

Further on it says: “Marxism is a Jewish invention… The Muscovite-Judeo commune is the enemy of the people!”

The text is among OUN documents published in “European Fascist Movements: A Sourcebook” (London and New York: Routledge, 2023)

OUN leader Yaroslav Stetsko, who proclaimed the independence of Ukraine in Lviv in June 1941, wrote to the Nazi leadership that “German methods are to be employed in the fight against Jewry in Ukraine”. The original Ukrainian-language version of his letter speaks more explicitly of “the expedience of bringing German methods of exterminating Jewry to Ukraine, barring their assimilation and the like.” Both documents are published in a 1999 paper by the researchers Marco Carynnyk and Karel Berkhoff in the journal “Harvard Ukrainian Studies”.

Swedish-American historian Per Anders Rudling, of Lund University, who specializes in eastern European nationalism, says: “Viatrovych just ignores what, by now, is a very solid body of literature. Among Holocaust scholars this is not a controversial issue, but established knowledge, based upon a wealth of sources - many of them in the ex-KGB archives of which Viatrovych himself was the director from 2008 to 2010.”

Polish historian and political analyst Lukasz Adamski, who has also done extensive research in the subject, says: “We don't have a written order [from the OUN/UPA, to kill Poles] with respect to Volhynia. But we do have an order with respect to Eastern Galicia, in 1944. Then, the commander-in-chief of the UPA, Roman Shukhevych, stated ‘First, you should you should encourage Poles to leave their houses and go to Poland - and then kill them.’”

In 2016, the Polish parliament declared that the Volhynian massacre was a genocide. That was part of a hardening of nationalistic attitudes on both sides of the border. In Poland, the right-wing populist Law and Justice Party, which took increasing interest in the Volhynian issue, had come to power in 2015. In Ukraine, the start of the war against Russian-backed separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk in 2014 led to increased interest in previous Ukrainian fighters against Russia, including the UPA.

In 2017, Ukraine banned exhumations of Polish victims of the UPA – though bodies of Second World War German soldiers could still be reburied. Historian Volodymyr Viatrovych – also a political activist with influential connections in government – played an important role in bringing about the ban. Kyiv said the prohibition was a response to Warsaw’s failure to repair fully a vandalised monument to UPA fighters in Poland. But the row only came to a head after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, when hundreds of thousands - later millions - of Ukrainians sought refuge in Poland.

“Polish people opened their hearts, their houses and they started helping,” says Karolina Romanowska, whose grandparents grew up in Volhynia. “It was not even a question. They are victims. This is what we have to do. But very often, Polish people would ask Ukrainians: ‘What do you think about the Volhynian massacre?’ We thought Ukrainians will finally see our pain from the past. And then I realised that Ukrainians don't know anything about this.”

Karolina became a prominent campaigner for the ban on exhumations to be lifted. Polish politicians took up the cause. And in the months leading up to Poland’s six-month presidency of the Council of the European Union, which started on January 1st, they threatened to block Ukraine’s steps towards greater integration with Europe unless reburials were allowed again.

Initially, Ukraine’s President Zelensky refused to give way, saying the issue could only be considered after the war with Russia was over. But in November 2024 Kyiv changed its position On November 26th came an announcement that “Ukraine would no longer oppose exhumations on its territory.” And then, ahead of a visit by President Zelensky to Warsaw on 15 January, came a deal to begin the work. The first exhumation will be on the site of the now non-existent village of Puzhniki – a long way south of Volhynia, in the far south-west of Ternopil oblast, near to the city of Ivano-Frankivsk.

The way ahead may still not be smooth, though. Each exhumation will require separate consent from Ukraine – and some Poles fear applications may sometimes be blocked by local authorities.

Ukrainian foreign minister Andriy Sybiha has said that in exchange Kyiv “demands proper commemoration of Ukrainian memory in Poland” including renovation of the previously vandalised monument to Ukrainian fighters. But that has not yet been agreed. And many Polish relatives of victims, including Karolina Romanowska, reject what they call a “transactional” approach to the issue. She hopes Ukrainian politicians will acknowledge responsibility for the Volhynia massacres and apologise.

On the Ukrainian side, historian Volodymyr Viatrovych fears Poland will now be emboldened to press for more concessions – and points to a Bill tabled in the Polish parliament by the Law and Justice party, now in opposition, that would make it illegal to “glorify” Stepan Bandera or “Bandera ideology”. It would also be a crime to display “Bandera symbols” – including the red and black flag used by the UPA that is now widely displayed in Ukraine.

If passed, the law would be the exact opposite of a Ukrainian law which criminalises “disrespect” for fighters for Ukrainian independence – including Bandera.

That law has never been used against researchers. But Ukrainian historian Georgy Kasianov, who has been highly critical of the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists, and now works in Poland, says “there is enormous psychological pressure when you write something and you know that perhaps you were doing something unlawful.”

Now, as a result of the row with Poland, a new debate on the events of 1943 and 1944 is beginning in Ukraine. The first detailed Ukrainian TV documentary on the subject, in the popular series “Realna Istoriya”, drew a wide audience. And Poles and Ukrainians are discussing the past at events organised by a reconcilation association founded by the campaigner Karolina Romanowska.

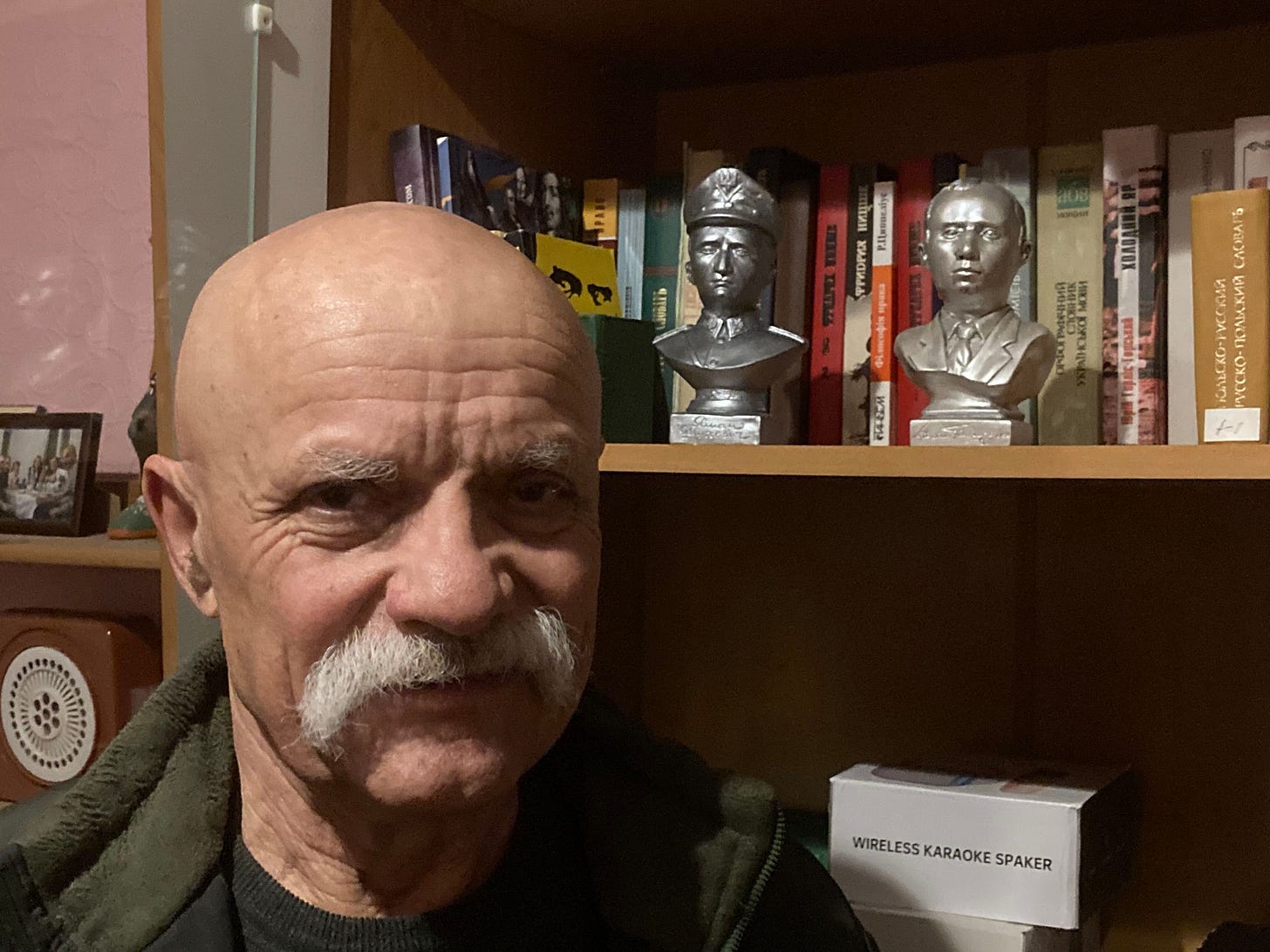

She has received letters of support from some Ukrainians, including Ivan Makar, an activist for Ukrainian independence in the 1980s, and later a people’s deputy of Ukraine, whose father joined the UPA in 1944, and who has small busts of Bandera and Shukhevych on his bookshelf. Makar, who describes himself as “the last political prisoner in Soviet Ukraine” (he was arrested in 1988 for “nationalist activities”) told me: “Karolina Romanovska and people like her have the right to take the bodies of their relatives and rebury them. Step by step we need to solve all this problems and find some common ground. History should not make conflicts between us.”

Karolina acknowledges that Russia has tried to use the subject of the massacres to divide Ukrainians and Poles. But she insists that when friends talk openly about a problem, their enemies can’t use it against them.

“If Ukraine is scared that touching the subject would question their heroes from the Second World War, I really believe that they shouldn't, because they now have real heroes, fighting for freedom. And those heroes, I believe, want Poland and Ukraine to be closer. This Volhynian massacre was a subject that that was hidden in the closet. And if you think a skeleton in the cupboard will disappear one day, you are wrong. I don’t blame Ukrainians for what happened. But if we will try to hide part of the history, that will not help us. That will only destroy us.”

Edited by Jenny Norton

The weaponisation of memory: why Russian courts are re-convicting Stalin’s victims

At the height of the Stalin-era purges and terror, to speed up proceedings and meet quotas required for guilty sentences, hastily-arranged ‘troikas’ - three-man secret police trial…