Massacre on the border: Could allegations of an Azerbaijani war crime in September derail Karabakh peace efforts?

Additional reporting by Paul Myers.

Accusations of war crimes continue to overshadow attempts to find a lasting settlement to Azerbaijan and Armenia’s long-running dispute over Nagorny Karabakh. Claims by Armenia that Azerbaijani troops shot dead at least eight Armenian POWs during a flare up in September, are the latest in a grim toll of unresolved killings allegedly perpetrated by both sides. BBC Russian has been assessing the evidence and asks how it will impact on ongoing negotiations to try to bring the conflict to an end.

As day breaks over the hill, a group of men armed with sub-machine guns, round up a group of prisoners at gunpoint and force them down onto the ground, hands in the air.

Shots ring out. Shouts of “Vurma, vurma!” are heard in Azerbaijani; “Don’t shoot!”. Shots continue to be fired as the prisoners lie on the ground.

This 40-second video clip filmed on a mobile phone tore across social media and Telegram channels in September, causing outrage in Armenia – where it was clearly interpreted as evidence of a war crime by the Azerbaijani army.

Armenia’s Human Rights Defender, Kristine Grigoryan, told the BBC that she had filed a complaint about the incident with the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR).

In early October, the office of the Azerbaijani Attorney General, responded to the allegations, saying that preliminary investigations had begun, and that “if the soldiers in question can be proven guilty”, then “the question of criminal responsibility can be settled”.

Although official information about the details of the incident are hard to come by, open source analysis by the BBC and other researchers has added a lot to our understanding of what happened and where.

Who pulled the trigger?

The video shows at least 15 soldiers surrounding a group of eight (or nine, by other sources) unarmed people in helmets and camouflage that match Armenia’s army uniforms.

The BBC checked this camouflage pattern against reliable photos of the new uniform and helmets used by Armenia’s armed forces.

The camouflage pattern of the uniform worn by the attacking soldiers matches the one used by the Azerbaijani army. However, it has not been possible to tell from the insignia to which precise unit the attackers belonged.

Researchers from Bellingcat reached the same conclusion - they compared the colour scheme of the uniform with patterns posted on the website ‘camopedia.org', which is a collection of different kinds of camouflage pattern from various countries.

On the pro-Azerbaijani Telegram channel where the video was shared, the post says that the soldiers that appear in the video belong to the ranks of Azerbaijan’s special forces (XTQ - xüsusi təyinat qüvvələri).

The BBC has listened to the recording and agrees with the conclusion reached by researchers from Human Rights Watch and Bellingcat, that that the word ‘vurma’ (“don’t shoot!”) is clearly being shouted in the video by a native speaker of Azerbaijani.

We don’t yet know what happened next with the prisoners, but experts agree that it’s unlikely any of them could have survived being shot with an automatic weapon at such close range.

Where and when the shooting took place

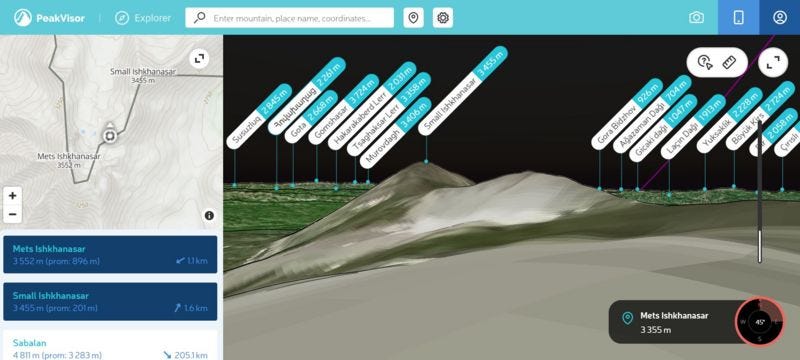

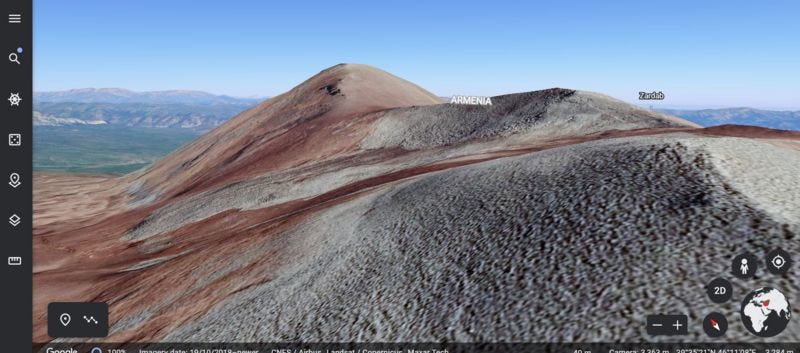

According to Armenia’s version of events, the incident took place on Armenian territory, in the mountains near Ishkhanasar, to the north of Lake Sevan, at a spot previously known as “Khоvаz-1”(shown by a red dot on the map below).

However detailed work by BBC specialists indicates that the actual location is in Lachin region, which is part of Azerbaijan, but was under Yerevan’s control from 1992 until 2020.

Our researchers took the coordinates provided by the Armenian Foreign Ministry and compared them to the landscape of the Ishkhansar mountains as seen in the video of the soldiers’ shooting.

They were unable to find a match, but by studying the camera angles, they identified a spot about one kilometre away, in the border area between Azerbaijan and Armenia, in Lachin region and inside Azerbaijani territory. (The spot is indicated by a blue dot on the map).

Pinpointing the exact time and date of the incident has also involved some detailed data analysis work.

Armenia says the incident took place on either the 13 or 14 September, during a border clash between Armenian and Azerbaijani troops.

Researchers from Bellingcat used time-location technology and satellite images, and also studied the position of the sun in the video. They concluded that the incident took place early in the morning – between 0600 and 0630, and that it happened sometime between the middle of August, and 13 September.

We know that fighting broke out in the area on the night of 12-13 September. So it is reasonable to assume that the incident took place early in the morning of 13 September.

What happened in September?

It’s still not clear what exactly sparked off the fighting along the Armenian-Azerbaijani border that lead up to the killings depicted in the video.

Azerbaijan blames Armenia for trying to lay mines on Azerbaijani territory.

Armenia blames Azerbaijan for invading Armenian sovereign territory.

However it started, the fighting resulted in a gain for Azerbaijani troops, who were able to take command of high ground along the border – a fact that President Aliyev was keen to stress in a speech in November.

Thanks to frantic diplomatic work, a ceasefire agreement was brokered between the two side, with both Russia and the US playing a role. The final death toll from the violence was more than 280 people.

Reactions and accusations flying

The emergence of the video showing the Armenian POWs being shot, has prompted strong reactions on both sides.

Armenia has accused Azerbaijan of committing a war crime, and has appealed to the European Court of Human Rights and the UN International Court of Justice.

Azerbaijan has promised “multiple follow-up actions” and says it had opened 10 criminal investigations into the incident. The BBC has not been able to confirm this.

Azerbaijan’s Deputy Attorney General Elchin Mamedov refused to comment, when asked about the situation by the BBC’s Azerbaijani Service. However he alleged that parts of the video were ”faked”.

Regional experts say that neither Azerbaijan nor Armenia have a good track record in taking steps to investigate possible war crimes.

“When a series of videos depicting torture of Armenian soldiers emerged shortly after the 2020 war between the two sides, Azerbaijani prosecutors also promised to act, and arrested some suspects,” journalists Joshua Kucera, Ani Mejlumyan and Ulkar Natiqqizi, wrote on eurasia.org.

“Those prosecutions appear to have foundered, however, and there have not been any convictions. At least one of the soldiers arrested in 2020 was in 2022 awarded a medal “for service to the fatherland.” Armenia has yet to launch any prosecutions for war crimes on its side.”

”A depressing read”

It was clear long before the September clashes and the emergence of the video, that few steps - if any - have been taken to try to rebuild trust between Baku and Yerevan, since Azerbaijan declared victory in the Second Karabakh war in 2020.

This was underlined on the anniversary of the conflict on 8 November this year, when Azerbaijan’s president, Ilham Aliyev, made a speech in the recaptured city of Shusha, saying the clashes in September were a “lesson for Armenia”.

“Depressing to read Pres. Aliyev giving the same speech in Shusha, calling Armenia “the enemy”... No change in tone,” Thomas de Waal, a Senior Associate at the Carnegie Endowment wrote on Twitter.

He pointed out that in the two years since the end of the 2020 war, Baku and Yerevan had not even been able to reestablish transport links as outlined in the agreement that ended the war.

Hostages of history

Why is violence still the default position, despite decades of talks to find a peaceful long-term resolution to the Karabakh conflict?

“The fact that military methods are favoured, should be viewed in the context of the whole course of the conflict from the very beginning,” says Dr. Leila Alieva, from Oxford University’s School of Global and Area Studies.

“In fact, military methods in a way compensate for the poor functioning (if at all) of international law in regulating relations between the states. For example, a country can violate internationally-recognised borders, as was the case in the First Nagorno-Karabakh war, without suffering any consequences from international organisations or the international community - no sanctions or other forms of pressure.”

Alieva is referring to the four UN Security Council resolutions adopted during the First Nagorno-Karabakh war in 1993, condemning the capture of Azerbaijani regions by Armenian forces and demanding the troops withdraw. It’s a major grievance in Azerbaijan that these resolutions were completely ignored and that Armenia suffered no consequences as a result.

If the failure of the UN resolutions has eroded faith in diplomacy in Azerbaijan, then the war in Ukraine may have further encouraged Baku to seek a military solution in Karabakh, according to some observers in Yerevan.

“Baku has shown an active policy of military diplomacy since the earliest days of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, by trying to take advantage of the obvious power vacuum in the Southern Caucasus and the considerable military imbalance between Armenia and Azerbaijan,” says Armenian political scientist Tigran Grigoryan.

If this is indeed Azerbaijan’s plan then it has certainly achieved some results since the border clashes in September.

As Grigoryan notes: “Armenia has already met Azerbaijan’s demands during the quadripartite meeting in Prague on 6th October 2022, and agreed to sign a peace treaty, and also to complete the process of delimitation by the end of the year.”

But even if Armenia and Azerbaijan are able to come to a formal deal at the negotiating table, many questions remain about whether either side would be able to sell that deal to their respective populations.

Any deal will involve compromises, but the more lives are lost and the more trust is eroded, the harder it will become to make those compromises on both sides.

In this context, unresolved allegations of war crimes can prove a particular hurdle.

How do you ‘sell’ a peace agreement to the people?

For the Armenian side, ceasefire breaches, and possible war crimes will make it much more difficult to sell a peace treaty to the wider population, says Yerevan-based analyst Tigran Grigoryan.

An idea has taken root in Armenia that the rest of the world is unfairly intruding on the country, he says. “Such sentiments only grow stronger after Azerbaijan’s war crimes.”

Journalist and author Mark Grigoryan agrees.

“In times of conflict, people suddenly start seeing society on the other side as some sort of monolithic whole, where there is no diversity of opinion and where they all deserve the same treatment,” he told the BBC.

“And a video showing brutality against defenceless people fuels the strongest possible negative stereotypes in Armenia about their [Azerbaijani] neighbours.”

In Armenia, Mark Grigoryan says, it’s common to call Azerbaijani people “Turks”, thus laying on them the weight of everyone’s emotions against the ‘real’ Turks and recalling the mass killings of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire from 1915-1923.

“You can really feel how the depths of hostility, resentment and loathing just got deeper still.”

In Azerbaijan there was very little public condemnation of the video showing the Armenian soldiers’ deaths.

In the public sphere, it’s rare to hear anything positive about Armenians. There are ongoing campaigns on social media against those who disagree with the military pressure on Armenia, using the hashtag ‘know the traitor’.

BBC Azerbaijani Service correspondents have witnessed how five- and six-year-old schoolchildren are taught in their morning assemblies to shout in unison, “Hatred! Hatred for the enemy!”, along with another slogan: “Karabakh is Azerbaijan!”

Transitional justice?

One of the main reasons hearts have hardened on both sides is that no war crimes have ever been effectively investigated either after the first or the second Karabakh wars.

It’s become the ‘new normal’ on both sides, says Zaur Shiriyev, Azerbaijani analyst with the International Crisis Group.

This is where the endless accusations of ‘they started it’ began, he adds.

Shiriyev is one of many observers on both sides, who argue that the key to a lasting peace between Armenia and Azerbaijan is an effective transitional justice system to address recent and past human rights violations which continue to stand in the way of reconciliation.

After three decades of conflict, there is very little trust left in peace in either Armenia or Azerbaijan.

In order for potential war crimes, like the incident on the border in September, to be properly investigated, there will need to be public support for the truth to be uncovered, says Shiriyev. That means an active civil society and a free press to call those responsible to account.

“Unfortunately, this side of the 2020 war, we aren’t seeing this active engagement,” says Shiriyev. “If these steps are not taken, then, unfortunately, we will have to watch as new war crimes are committed, and societies on both sides will find ways to justify them.”

Read the full story in Russian here.

Translated by Elsa Haughton.