LONG READ: Inside a war crime - the medics, mums and babies who survived the Mariupol hospital attack

In March 2022 the world was shocked by photos of pregnant women staggering through the wreckage of a bombed out maternity hospital. BBC Russian hears their devastating stories.

By Olesya Gerasimenko.

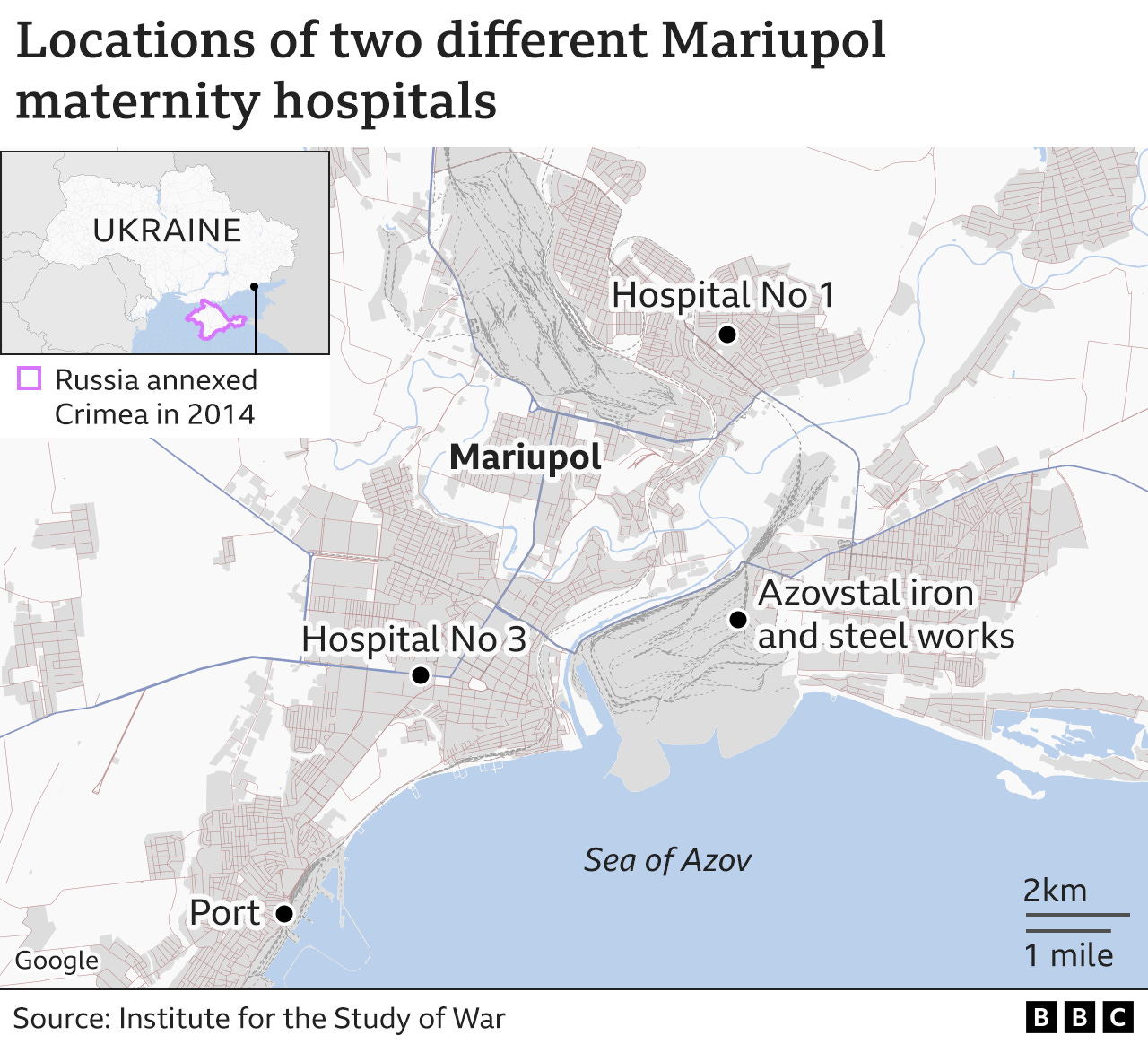

On 9 March 2022, Maternity Hospital No.3 in Mariupol was hit by a Russian airstrike. Photos of pregnant women covered in blood, staggering out of the wreckage shocked the world. One year on, Olesya Gerasimenko has spoken to some of the survivors - the women who gave birth by candlelight as the fighting for Mariupol raged around them, and the doctors who carried on working in the hospital even after it was bombed. It will probably take years to piece together a full picture of what happened in Mariupol last year, but the story of Hospital No.3 offers a searing glimpse into life in the city during its darkest days.

The names of most of the interviewees in this story have been changed in order to protect their safety. Their full names are known to the BBC and we also have personal documents, audio-recordings, photos and videos confirming their identity.

Elena Kramina from Mariupol gave birth to her first child on 11 June 2014. At 7am, doctors on the maternity ward at Hospital No.3 cut the umbilical cord, her daughter cried, and the midwife prepared to weigh her. The whole ward could hear the sounds of shells as government troops fought to regain control of the city from separatists from the self-proclaimed Donetsk Peoples Republic. “Back then, we were always joking, hey, she’s a war baby! Nobody imagined there’d be another – a real child of war.” The shelling in 2014 was soon over, and the family stayed in Mariupol.

On 24 February 2022, Elena’s daughter was seven years old, and she herself was nine-months pregnant. Her husband worked in the Azovstal iron and steel works and she was an instructor in a technical college. On Thursday morning they stood at the window, watching smoke rise over the neighbourhood. Confident that things would pass and everything would be alright like in 2014, they packed their toothbrushes and set off to spend the next few days in Elena’s mother’s village. The doctors had pencilled in 6 March for Elena’s delivery date, and the couple left their pyjamas and bag of nappies for the hospital by the door to their apartment. They were sure they’d be coming back.

“And as we left, we saw them bringing military equipment to Azovstal, we heard sirens all over the city, and saw the buses turning round. Even at that point, they’d stopped leaving the city.” Although she didn’t know it, Kramina was seeing her home for the last time.

Preparing for an emergency

Whilst Elena was heading to her mother’s, Aleksandr Martyntsov, the 70-year old head of paediatric surgery at Hospital No.3, was heading into work. He was born and trained in Mariupol, and started practising in 1975. His home-from-home was the hospital, the only children’s hospital in Mariupol. It was a big hospital with multiple wards – a maternity wing, two somatology departments, an infant mortality centre, and departments for neurology, surgery, traumatology and intensive care. There was also an oncology clinic in the hospital grounds.

Before the war, the hospital offered round-the-clock care, seven days a week, with even paediatricians working to a strict shift pattern. Staff turnover was low – heads of department served for 20 to 30 years, with specialists staying even longer.

On the morning of 24 February, after phoning his daughter to discuss the outbreak of war, Martyntsov started his 7am shift. He wasn’t afraid of the explosions: “In the past, we were always hearing artillery. Missiles flew overheard – but they were always heading for DPR territory, they never touched us in the centre.”

The hospital authorities told staff to prepare to work in emergency mode. Cancel all routine appointments, stockpile medicine and water, and prepare for mass casualties. All children in recovery were allowed to leave. A few remained with serious cases of peritonitis. Doctors carried on working 24/7 and admitting patients. But few parents were now bringing their children in, says Martyntsov.

As the days passed, Elena Kramina began to panic. Giving birth in the village without a doctor hadn’t been part of her plan. “I started pressuring everyone, saying I had to be taken to hospital. I didn’t know I’d be heading straight into the eye of the storm. I couldn’t have imagined it.”

An ambulance came for Elena on 28 February – it was a favour, as a family friend was one of the crew. The city was almost surrounded. “We’ve pretty much stopped responding to these kind of calls,” the ambulance driver said. Elena’s husband came with her. Their daughter stayed with her grandma. Elena was brought to the maternity ward of Hospital No.3, on Prospect Mira.

The hospital was already packed with pregnant women from all over the city, suburbs and surrounding countryside. Women like Elena, due to give birth in a week’s time, didn’t want to stay at home under shellfire. Many arrived on foot. Someone had hitchhiked.

Doctors were also transferring premature babies and children with cancer from the postnatal centre on Metallurgicheskaya Street to Hospital No.3. Mariupol residents interviewed by the BBC said that the centre was requisitioned by the Ukrainian Army on 1 March, and all the patients and their doctors were evacuated to Hospital No.3.

Not everyone was happy that the postnatal centre had been closed down, remembers Mikhail Vershinin who was head of the Donetsk Regional Police at the time of the Russian invasion. He was captured by Russian forces and eventually returned to Ukraine in the autumn of 2022.

“The front was getting closer and closer to the postnatal centre,” he told the BBC. “Everybody needed to leave. People had to be evacuated – dragged out by force, if necessary. Naturally, not all the civilians would listen. I understand why doctors might be angry, but they aren’t seeing the full picture.”

As Kramina recalls, the maternity ward of Hospital No.3 was soon overcrowded. Both the paediatric ward and the prenatal ward were filled with heavily-pregnant women. Elena remembers eight women in her room, and at least six other similarly crowded rooms.

By 2 March, the city had been surrounded for two days, and 30-year-old Irina Solovyova arrived in the ward. Two months earlier, she and her husband had bought a new four-bedroom apartment. Their youngest son, not yet two, had his own room. Irina’s husband, who ran a workshop in the Azovstal plant, had taken a month’s leave to be with his family and support his wife. Her due-date was in early March.

“In the beginning, our part of town wasn’t affected,” says Irina’s husband, Vitaly. “We didn’t know what was coming, so we stayed. And it was dangerous to leave, our neighbours were scared of being shot in the street.”

“We need to run! We’ve got to get out quickly!” 30-year old maternity nurse, Tatiana, remembers shouting down the phone to her policeman ex-husband, on the first day of war. “He said, Tanya, the city’s closed. I said, how do you mean, closed? And he says, well, the city’s closed, nobody can leave.”

“It was utter chaos. People only came to work if they felt like it, and those who didn’t stay away. We had no light and not enough generators. There were seriously ill kids lying under oxygen for two hours, and then resting for two hours. Nobody really knew how best to nurse them.”

A number of people the BBC spoke to for this story seemed to believe rumours that the city was closed and no-one was allowed to leave. But the BBC has found no documents, or photo or video evidence to show that this was actually the case.

Donetsk Regional Police chief, Mikhail Vershinin, said such claims ‘did not correspond to reality”.

“You could absolutely leave the city, right up until 28 February. After that, when the city was encircled, it became impossible. We couldn’t send people out into the unknown, under Russian fire, when there was no suggestion of even a temporary ceasefire,” explains Vershinin.

In a statement to the BBC, the strategic communications department of the office of the Supreme Commander of the Ukrainian armed forces said that the army had never blocked the exit roads from Mariupol, but continuous shelling made it very difficult to get civilians out of the city safely.

“The Russian side constantly blocked humanitarian corridors, but the Ukrainian government made maximum effort to organise humanitarian corridors and successfully evacuated about 75,000 people from Mariupol.”

By 1 March there was no water, electricity or gas at home, the city was completely surrounded, air-raid sirens were sounding almost constantly, and Irina Solovyova, her husband Vitaly and her son went down to the basement to take shelter. The next day the shelling was closer by, and Irina began to feel some contractions. They called an ambulance “which was still possible at that point”.

Solovyova phoned her husband from the hospital to let him know she’d arrived – it was her last call. There was no signal from then on. Irina remembers that the maternity hospital was still intact, but buildings in the surrounding area were ablaze. “There was fighting all around us. Missiles flying. I stood at the window and watched them falling.”

Irina and Elena found themselves neighbours on the ward.

The shelling draws nearer

Valeriya Arkhipova, a neonatologist, arrived for work on the maternity ward at the same time as Irina. She was an experienced doctor who had worked in infant mortality and intensive care for nearly 14 years. As she began her shift on 2 March, Arkhipova had no idea that she wouldn’t leave the hospital again for another month.

“After 2 March, a lot of doctors stopped turning up for their shifts,” Arkhipova recalls. “Nobody came to replace me, they told me they were too scared. We neonatologists were left with one young doctor, who’d only recently qualified.”

“It was utter chaos,” adds one of the nurses, describing the beginning of March, “People only came to work if they felt like it, and those who didn’t stay away. We had no light and not enough generators. There were seriously ill kids on oxygen for two hours, and then resting for two hours. Nobody really knew how best to manage their treatment.”

Many doctors fled Mariupol on 24 February while they still could. Others were unable to get into work as the shelling got worse, patients say. But there were those who stayed. Elena and Irina remember a nurse walking to work under shellfire. They also have warm words for the head of maternity, Sergei Sverkunov: “He should have a monument put up in his lifetime. He was with us to the last, never went home, delivering babies for four days straight. We were all saying prayers for him.”

On 2 March water and electricity supplies were cut across the city, and in the hospital too. Eleven women went into labour in the dark: “as if on purpose,” they joked, afterwards. They were brought into the operating room with candles, and the generators had to be turned on twice, for two caesareans. “The doctors did such a good job, I couldn’t believe it,” says Elena.

Volunteers brought barrels of water to the hospital. An oxygen supply was left outside for patients with complications - 12 cylinders. Arkhipova looked after the new-borns as best she could. Those who needed oxygen stayed on the ward, and the others were moved to beds in the corridor. Amongst them were twin baby boys.

There were men in the yard outside the hospital, mostly fathers-to-be who hadn’t found anywhere to spend the night in town. They lit a campfire and boiled water in a 50-litre pot, which they then. siphoned off in kettles. Rescuers brought meat and ‘kasha’, which they cooked on the fire.

Later, they stopped bringing food and water to the pregnant women. If one of the men did bring water, the women wouldn’t drink it. Instead they split the boiling water equally into thermo flasks, and used it to sterilise the stitches after births.

In the hospital basement there were a lot of people from other parts of the city – women, teenagers, families. When the pregnant women found out about this, they were indignant: “There was nowhere for us to hide if something happened. The cellar was already packed. It was horrible, – dark, screaming kids, and unhygienic conditions – one person gets sick, everyone gets sick. Pregnant women couldn't go down there, of course, everyone would have been infected at once,” remembers Solovyova.

The shelling intensified, with tanks rolling ever closer to the hospital. Surrounding buildings caught fire, and the first glass flew from the windows of the maternity ward, Arkhipova recalls. All the BBC interviewees state that it was impossible to tell who was firing, and from where. At 5am on the morning of 5 March, a shell exploded right in front of the maternity ward, blasting away the doors and windows on the ground floor.

To Elena, who recently arrived from her mother’s village, it seemed that “the rumbling was drawing nearer,” but the girls who came from areas closer to the fighting thought the opposite. “I would be trembling and shaking all over, and they would just wave a hand and say - it’s a long way off. But all our knees were blue with bruises – because at every strike, the doctors would order all the pregnant women to get down on all fours in the corridor.”

The first mass civilian casualties

Surgeon Aleksandr Martyntsov carried on coming to work on foot. On the morning of 6 March he fed his bedridden wife and left for the hospital. He recalls that the street was full of people “as if there was a demonstration,” only each of them was carrying a flask instead of a flag. All Mariupol was out on the streets in search of water.

“We still had a lot of Russian sympathisers. They said, it’s just Russia, they can’t do something like this, everything will be okay. They’ll just shoot for a while and then leave.”

En route, Martyntsov cut through large courtyards in front of blocks of flats. There were hundreds of people sitting outside by campfires. They were making porridge and soup – there was still no gas or electricity. “Everyone was pretty calm, verging on cheerful –sure, we could hear rumbling in the distance, but we still weren’t taking it seriously.”

However, when he got closer to the hospital Martyntsov could see a queue of ambulances at the entrance to the building: “We’d never had anything like that.” Inside, three operations were already underway. “Quickly,” the nurses greeted him. “Into the operating theatre, there are so many wounded.” The shelling of central Mariupol had begun.

That evening, Aleksandr saw again some of the people he’d seen earlier carrying flasks or sitting around campfires, only this time they were being carried into his ward on stretchers.

According to the surgeon, on 6 March the Russian army first started firing missiles into the streets and courtyards where people were looking for water or making fires. “It was like a safari for them. Like a hunt, understand? The whole neighbourhood was out on the street. People just didn’t have time to understand what was happening.”

It was already night-time when Martyntsov got his first chance to leave the operating theatre for a few hours break. He kept up this pace for three days. “Three days was how long it took people to understand that they were being killed, that they had to hide. We still had a lot of people who were sympathetic to Russia. They said, it’s just Russia, they can’t do something like this, everything will be okay. They’ll just shoot for a while and then leave. And only after those three days of mass shooting did people realise they were being killed – then they started hiding.”

Blood quickly soaked the hospital bedsheets. There was nowhere to wash them. Railway workers came to the rescue bringing a fresh supply of sheets and pillowcases from the sleeper cars of trains that are no longer running.

After people started hiding in basements, the flow of wounded patients subsided. Nonetheless, Martyntsov worked round the clock for the next ten days: amputating arms and legs, sewing up intestines and abdominal cavities, and taping ribs. Only patients with shrapnel wounds to the head were sent to the regional hospital, where neurosurgeons worked under fire.

Vanishing hopes

“After the shelling on 6 March we lost all our illusions that everything would be alright. We knew it would all be difficult, from then on,” says Arkhipova, the neonatologist.

At this time, according to Elena and Irina, tanks began to gather outside the oncology clinic, which was just 200 metres from the maternity and paediatric surgery wings. “Ukrainian soldiers appeared in the building. We thought, this is probably it, this is the end.”

Irina Solovyova describes seeing troops “digging trenches”. “Our building was U-shaped,” she said. “We were in one wing, and they were on the other side.” Two other interviewees told us the same story.

The BBC has studied satellite images of the hospital on the day of the airstrike and can see no trace of either tanks or trenches in the grounds.

When the BBC asked Dr Arkhipova if it was true that there had been Ukrainian soldiers in the hospital grounds, she sighed: “Can I not comment on that please”.

Later doctors told journalists that the military hospital in the city had run out of beds over those few days, and so had sent new patients to the hastily-equipped oncology clinic at Hospital No. 3.

Both Dr Martyntsov and Mikhail Vershinin, the former police chief, confirmed to the BBC that the oncology clinic was briefly used as a field hospital to treat wounded soldiers. But Martynstev said it had been ‘quickly folded up’.

Vershinin is indignant at the suggestion that there were anything other than wounded soldiers briefly being treated in the clinic in one corner of the grounds.

“The patients at the Maternity Hospital wouldn’t have been able to see troops, because they weren’t there,” he told the BBC. “Your informants seem to have conspired to discredit the Ukrainian Armed Forces in the city. Thеre are things that happened in Mariupol which upset me, but this isn’t one of them.”

“Everything went into slow motion, like a movie. You couldn’t hear anything, only see that cabinets and the whole wall were flying towards you.”

The BBC asked the Ukrainian army to comment on claims that there were Ukrainian soldiers deployed on the territory of the hospital. In a statement, the strategic communications department of the office of the Supreme Commander of the Ukrainian armed forces said:

“Information about the organisation, number and location of units of the Ukrainian armed forces and other military formations is classified as a state secret … but unlike the representatives of the armed forces of the aggressor state, they do not base themselves in functioning medical facilities in order not to endanger civilian lives.”

In a 29 June UN report the office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights expressed concern that between February and May both Russian and Ukrainian forces had taken up positions in residential areas or near civilian objects “from where they launched military operations without taking measures for the protection of civilians”. The report gave details of two locations in Ukraine where this had happened, but it did not mention Hospital No. 3.

Baby Boy

At 10pm on 7 March, Elena Kramina had a baby boy, born in the ward by candlelight. The baby was delivered by Sergei Sverkunov, the head of department. “They put us in a freezing maternity ward. Ten blankets on top, you can’t budge, everything hurts,” she remembers.

In the seven wards where women had already given birth, old mattresses were lined up in front of the window-sills, and blankets covered the windows. In the east wing, where women were still waiting to give birth, the patients themselves sealed the windows with tape – there was no other protection.

On 8 March it started snowing and the temperature dropped. The whole day was quiet. Elena rejoiced: “We convinced ourselves it was all over, that we’d be going home as normal."

But Irina Solovyova, who’d given birth that day at one in the morning, was worried. “You know how scary it is to give birth? I was lying on the operating table, praying. Because for me, the silence was the scariest thing of all. We’d all got used to the bangs.”

Disaster strikes

On the following day, 9 March at around 3pm, Dr Arkhipova was in the intensive care ward with a nurse, checking on twin baby boys. One baby was stripped down to his nappy to be weighed. The other was lying in a transparent incubator with tubes in his nose, his mother stood close by. The oxygen compressor was humming loudly. It was clearly audible, the doctor recalls, because the street was quieter than usual, as it had been the day before.

And then suddenly there was an explosion.

“Everything went into slow motion, like a movie. You couldn’t hear anything, only see that cabinets and the whole wall were flying towards you. The twins’ father wrapped his arms around me, and we fell to the ground. I was lying there. I opened my eyes and I couldn’t hear anything.”

“I started to get up, and I turned my head – and could see one of the twins lying on the floor in his nappy. I picked him up and hid him under my robe. Everyone else was trying to get up.”

According to Dr Arkhipova there were two explosions, one after the other. She thought the second seemed more violent, detonating those 12 cylinders of oxygen that were standing outside the building. “They flew into the air, blown to bloody smithereens.”

One of the nurses was pinned under a cabinet. In the corridor, mothers and their children were covered in shards of plasterboard walls and ceiling.

Elena was sitting in bed holding her baby – and a second later, opened her eyes to find herself on the floor under the bed. “The baby was underneath me, everything around me was shaking, and out of fear I crawled further under the bed. Then I realised I had to do the opposite – crawl out. I was backing out, and was hit by a window frame. I freed myself and ran downstairs. It was a miracle that only my knee was injured, nothing else. The head of department, Sergei Petrovich, led us outside.”

Elena saw a girl walking out of the delivery room in a cotton hospital gown, stone-faced with a baby in her arms. She had given birth just ten minutes earlier and was having her vaginal tears stitched at the moment of the explosion.

Irina Solovyova was standing by her baby’s cot when the explosion hit. She was saved by one of the mattresses blocking the window. “I fell down, shards fell on top of me, I still have the scars on my back, hands, and face. The room seemed to crumple after the blow. Honestly, I didn’t even cry, I was so in shock, I couldn’t understand a thing. It was such a strong blast wave that I was thrown off balance, but I braced myself with one thought in my head: “Milana.”

Scooping up her daughter, she ran into the street, barefoot in her robe. It was minus eight degrees outside.

“They were shouting at us, to go down to the basement,” remembers Arkhipova the neonatologist. "We went down, carrying the babies and the incubators. There were around 300 people there already – adults, children, they’d been brought there from all over the city. It was airless. There was nowhere to sit, no room to turn. Then we heard soldiers shouting through a megaphone, telling everyone to get outside. So we all ran.”

Through the corridors and up the stairs they hurried, pregnant women and those with infants. “They’d been badly hurt,” Elena says, referring to the mothers-to-be. “I saw girls covered in blood, because there was no kind of protection or shelter in their rooms. One woman, Vera, 35 years old, had lost three of her fingers. Another girl – she was 19, had hit her head and had blood pouring down her face. A shard of glass struck her stomach on the left side. This glass pierced her belly, it went into the baby and into her.”

Although doctors at the regional hospital battled desperately to save her life, this young woman would die several days later. She was the only casualty amongst the patients in the maternity ward on 9 March. She had been moved to the bed which Elena had occupied before she gave birth twelve hours earlier.

“The floor lifted up and the ceiling crashed down on us.”

Five operations were carried out at once in Martyntsov’s surgery department on 9 March. In normal times, there could only be two. But now, the doctors had improvised a third table, with a gurney put in the corridor and a stretcher placed next to it where they could also operate. In that way, carrying out five operations simultaneously was possible.

There was a brief moment of calm, which saw a team of traumatologists, surgeons and anaesthetists gathering in the dressing room to talk. They were waiting until the operating room was ready. That only happened after a nurse had cleaned a narrow path for the doctor to walk across the blood-soaked floor. It was impossible to wash the entire operation room – there was so much blood that the surgeons could not get to the operating table without slipping on the white tiles, which were covered with blood. “It was ankle deep in there - the floor, walls, tables, everything was flooded,”says Martyntsov.

“We were standing there and suddenly heard a terrible explosion. We didn’t understand what was happening, though we thought it was the end. It was such a huge blast that the floor lifted up, and the ceiling crashed down on our heads. We were lucky it turned out to be a suspended ceiling. We fell and waited for the roof to fall in on us.”

The doctors thought that the shell had hit the surgical building, which was located two hundred meters from the maternity unit. However, employees from the maternity unit then came running, shouting that a bomb had been dropped on them.

“We couldn’t leave the operating room, so we got ready to receive the wounded.”Several women who were in serious condition were taken to the regional hospital. Others were sent to Martyntsov’s department. Just 20 minutes after the explosion, one woman gave birth on a stretcher whilst she was being carried away for surgery. Luckily, both the mother and child survived. Martyntsov operated on two other pregnant women - one had a “huge hole” on her left shin. She was injected with painkillers and treated for the wound whilst lying on the floor. The second one was sewn up after being anesthetised in the operating room.

Fleeing to safety

At the exit to the maternity hospital, Ukrainian soldiers guided doctors and patients to cars. Elena and another woman in labour were taken to hospital No. 17. “They gave us mattresses in the corridors. There was no light. The hospital building was on the front line - there were clashes going on there, and the doctors were outraged that we had been brought there with our babies into the middle of all that chaos.”

Irina Solovyova was taken to a military field hospital in the building of what used to be Hospital No. 5, now on the territory of a military unit. “It was four floors crammed with wounded soldiers. Civilians were hiding there because rockets were falling everywhere and destroying houses. I kept begging to be taken home, which was 20 minutes away. A fighter jet was flying over the hospital, and I thought that I was about to go through the same hell for the second time.”

There was a heavy gun stationed in the courtyard of the hospital, which fired at Russian troops when they arrived, says Irina. The BBC has studied satellite imagery of the hospital on 9 March and was not able to either confirm or disprove this claim.

“And at the same time, people were also being brought in from under a nine-storey building which collapsed. I saw those who were injured in that incident. There was blood everywhere, unsanitary conditions, explosions all around - and I was with the baby.” Irina spent the night on mattresses in the corridor. “I cried all the next day and said to myself, if no-one takes me home, I’m going to leave by myself. I held the baby to my breast. I was determined to be able to keep feeding her.”

Irina was taken home. In the yard she saw her mother coming out of the basement with her husband and son. Irina went upstairs to the apartment and collapsed on the floor. It was only them that she realised she had spent two days barefoot.

”Will you tell your daughter how she was born?”

“I am not sure. She might be proud that her mother survived given the situation. But honestly I just keep thinking how could I have left my passport, diapers, phone, and money behind. As l fell, I lost my slippers and was stepping on glass on the ground as I was running … I still don't believe this happened to me.”

Later in the summer, OSCE experts and the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights came to the conclusion that the airstrike on Hospital No. 3 was deliberately carried out by the Russian military, and recognized the incident as a war crime. The Russian Ministry of Defence has not yet claimed responsibility for this attack, having tried several times to prove through the media that it did not happen at all.

Tragic postscript

Although all the staff on shift that day in Hospital No. 3 survived, fate had other plans in store for some of them.

Olga Fomenko, the head of the Department of Infant Pathology, also helped save patients. Since the beginning of the war, she had made her way to work every day from the basement of a neighbouring house, as her apartment had been burned down.

Fomenko had worked in the maternity hospital for more than 30 years and was extremely strong willed, doctors recall. After the explosion a plasterboard wall fell on her and her nurses. Minutes later she was already asking:

“Is everything ok?”

“Yes, everything’s ok.”

“Why are you lying down then, get up and get back to work!”

Fomenko survived the explosions, helping patients get to other hospitals. When she returned to the basement of the nine-storey house where she had found temporary shelter with her husband, her heart stopped.

Tatiana Levina worked as a nurse in the maternity hospital up to the very end. Pregnant women remembered her, because even after the power outage when water was first distributed to those giving birth, pregnant women remembered Tatiana bringing boiling water for tea on the wards. Her pregnant goddaughter was admitted to the maternity hospital. “When the maternity hospital was attacked, she was on shift. But they both managed to escape,” says Elena. But on 12 March, Tatiana and her goddaughter came under fire at home. The nurse shielded the pregnant woman with her body. Although the goddaughter's legs were broken, her unborn child was unharmed. But 41-year-old Tatiana was not so lucky. She had to be “buried in pieces.”

Fleeing barefoot to the basement

The following morning, 10 March , Elena Kramina's husband went to see his wife, setting off from his aunt's apartment nearby where he was spending the nights. But instead of the maternity hospital, all he saw was ruins. There was not a single patient in sight. Her husband started running around the grounds, shouting frantically. Dr Arkhipova the neonatologist, came out of the surgery department and told him to look for his wife in other hospitals.

He finally found Elena with other injured people in Hospital No. 17. She was sitting barefoot just like Irina.

“We had never experienced it in real life before, only in textbooks at medical school. In the first few hours we were just getting used to the injuries that were coming in, internal damage from shrapnel wounds.”

He took her and the baby back to his aunt's apartment. Elena lay down on the sofa at home for the first time in weeks. She had just closed her eyes when a shell exploded near the house. “From the windows to the wardrobe - everything was ripped apart and rained down on us with the child. And once again we had to run barefoot to the basement.”

Down in the basement, the baby's temperature rose to 39°C. The family was lucky that there were some doctors hiding from the shelling in the same basement, and they were able to help by giving the baby an injection.

The next day their building took a direct hit. “While we were in the basement. Five floors collapsed like paper.” The explosion left a big hole, and Elena, her husband and child managed to climb through and get out. They ran to the house of another aunt across the city at dusk, though this time luckily someone had lent Elena a pair of boots. They stayed at the aunt's house for another week and couldn't leave, as everything around was on fire. All this time, Elena managed to keep breastfeeding her baby.

Dr Arkhipova and her neonatal colleague stayed on in the hospital. They took the children and moved them to the surgical building. In the building there were also three babies from the maternity unit receiving specialist care. The head of the maternity unit was also with them.

“There were no options for evacuation, no humanitarian corridors. We couldn't leave Mariupol by ourselves. We were sitting ducks,” says Arkhipova.

Attempts to negotiate a pause in the fighting in order to evacuate civilians rarely succeeded.

“The Russian side blocked evacuation routes and humanitarian corridors, deliberately putting civilians in danger,” the Ukrainian army’s strategic communications department told the BBC in a statement. “It was precisely the actions of the Russian soldiers that lead to a significant loss of civilian life and caused a humanitarian crisis in the city.”

“First the mortars, then Grad missiles, artillery, massive shelling, and then tanks advanced on the ground,” one survivor of the hospital attack told the BBC. “We were nothing to them.”

Military trauma

On 10 March, Dr Martyntsov walked through the ruins of the maternity unit: “It was impossible to work there,” he said. He gathered up all the remaining painkillers and other medication. He also managed to get into the oncological dispensary: “The military did not take anything with them when they left, they already had their own good supplies.” Sо he took everything that was needed by his surgical team - the more expensive painkillers, ready-made dressings, sterile wipes, without which abdominal operations would be impossible.

Over the coming days Dr Martyntsov - a paediatric surgeon, had to learn how to deal with a growing stream of injured adult patients. He recalls how he adapted to the situation. “We have never worked on adults, we work on children. We are very good paediatric surgeons, the only ones in Mariupol. And then the wounded arrive… You see, I can operate on newborns, weighing only three kilograms or so. But suddenly I was dealing with adults weighing 120 kilograms, with unimaginable subcutaneous layers of fat. But actually, I found it easier. On the little ones, everything must be done with microscopic care, but on grown adults you have much more room to operate!”

“But this is military trauma. We had never experienced it in real life before, only in textbooks at medical school. In the first few hours we were just getting used to the injuries that were coming in, internal damage from shrapnel wounds. We had never experienced this. There may be just a small hole in the stomach, but inside the fragment will have destroyed everything. Shards in the intestines usually cause so much damage that it requires an assessment of all organs...”.

Children were also brought to surgery. Martyntsov remembers a 7-year-old girl who had a shard removed from her leg, and fortunately survived. However, she was unable to walk home after the operation. So her parents put her on a little chair and made their way home as quickly as they could under shellfire.

Then there was the 12-year-old girl, who died when her home was destroyed in a strike. Her mother was also badly injured. Her father drove them both to hospital but the mother died on the way.

Martyntsov tells how two boys under the age of three were brought in. They had been found sitting on the street next to their dead mother. They were freezing and didn’t understand why their mother wouldn’t get up. He remembers a 5-year-old girl who was brought in by her parents. She was close to where an explosion occurred and had serious head injuries. She died as a result.

And finally he remembers a 15-year-old teenager from a village nearby who went outside into the yard and was killed when a mine blast knocked him flying and he hit his head as he fell. He was placed on the mountain of corpses that grew at the hospital’s main entrance. There were roughly 40 frozen bodies on the street. The boy lay there for three days while his parents tried to figure out how to bury their child. Eventually they took him away and buried him in the yard of their house.

Survival strategies

Dr Arkhipova stayed on at the hospital, living in the surgical department. She carried out operations helping wounded pregnant women. There were fewer and fewer doctors. Someone found a road safe enough to evacuate their family. Someone decided they couldn't work anymore. Someone left the ward and didn't come back. Dr Martynstov says he and his remaining colleagues were often left wondering if they had been killed on their way home.

According to Dr Arkhipova by the middle of March, the only staff still working in the hospital were a paediatric traumatologist, a paediatric surgeon (Martyntsov), a gynaecologist, two neonatologists, a doctor from the perinatal centre, five nurses and two anaesthetists.

“Why did you stay on?’

“First of all, other than us, who was there for the children? There were abandoned children without parents. We couldn’t leave them to die.”

The doctors ate a bowl of oatmeal porridge a day, cooking it on a fire at the entrance.

“I haven't eaten porridge since childhood, and back then I didn't like it at all. Now I think there’s nothing more delicious,” says the head of the surgical department. “Once a Grad missile shell landed right in the cooking fire. Everyone ran for their lives. Every hour they were afraid it would happen again. “

After having to operate for a month under shelling, the doctors devised their own strategies for survival:

1. Trust your inner voice. One day something told Dr Martyntsov to get off the couch where he had been taking a break. Three minute later a shell landed right where he had been sitting. “While I walked out into the corridor from the staff room, the shell was already in the air... I saw the couch afterwards. Whoever had been sitting there would have got three holes in the head, chest and stomach. I thought to myself, would there be enough time to operate? But then I remembered that I was the only surgeon left...”

2. Don't close your eyes. “It was only later when I had time that I started to sit and remember what it was like during that time. If you closed your eyes, then everything would be black and mines would explode in the background. There are no other memories there. There's only blackness and explosions. That's why I tried not to close my eyes.”

3. You won't hear the shell which will hit you. The next one could be yours.

The brutal laws of triage

As the shelling intensified, Dr Arkhipova went down to the hospital basement with the children. She says that one premature baby from the maternity centre died there. The child froze and ran out of oxygen.

“How did you cope with that?”

“Well, I’m not seeing a psychologist. But let’s put it this way - I will never forget it. It will always be there in my head. You just have to learn to live with it. Compared to what we experienced there - everything else seems like nothing. And... damn it, I don't even know how to say it, but do you know what the worst thing was? Have you heard what military or police triage is?”

“I found out during the pandemic. The doctor needs to decide who he will attempt to save and who he will leave to die.”

“Yes. Only here we had to do it with new-born babies. I wanted to shoot myself. Three died. We knew there was nothing we could do. In normal times, we would have been able to save them.”

Dr Martyntsov had also never encountered triage before the war. “We had heard about it theoretically… but then we were overwhelmed with those wounded. Everyone was on the floor… with the doctor walking down the corridor looking at the injured. They would be lying there wounded and looking straight into your eyes. Those who were unconscious would be lying quietly, unable to help themselves in any way. Others would be yelling. Of course, the doctor would first react to those who screamed the loudest...”.

Who should be seen to first? “Well, you can't tell someone who screams loud that he's the twentieth in line - he'll just die of shock on the spot. Many have died on the spot from shock - literally from horror, although the injuries they had were non-fatal. So they lie there scream. According to the laws of wartime, we must prioritise those who are unconscious. The doctor has a few minutes to select the patient and take them to the operating room.”

According to the law of triage in both wars and pandemics, doctors should deal with those who have a chance of survival, and leave those who they are less likely to save. “I knew about this law. But we are still paediatric surgeons… and I couldn't come to terms with this.”

According to Martyntsov, who was only involved in complex operations, approximately 70-80 patients a day came with moderate injuries. Though there were days when surgeons were attending 100 people daily.

Every day, the senior physician managed to visit and bring food to his wife in the apartment where she was staying, even under fire. He ran zigzags, hiding behind concrete slabs to avoid artillery fire. But on 20 March, he approached the house and saw that all nine floors were on fire, with three floors missing in the middle. He turned around and went back to the hospital. He never went home again. He does not know how exactly his wife died - he tries not to think about it.

A few days later, after the Ukrainian military left the hospital, they took one generator from the doctors, Dr Arkhipova says. The second generator only had enough power to last for the next two days. By this time, the doctors’ daily rations were down to one biscuit and half a glass of water a day. They tried to save water so there was enough to make up the baby milk.

Enter the DPR fighters

On 23 March, a battalion of fighters from the separatist DPR came to the hospital. “The soldiers came – shameless and strolling in,” says Martyntsov. “We went to the first floor where the wounded were lying. The surgeons were somewhere else at that time and only two nurses remained there, who were normally calm older women. However, at this point the patients were virtually like children to these nurses, and they were taking care of them around the clock without resting. The nurses were extremely wound up.

“When the DPR people turned up at the hospital, the nurses were outraged and overcome with anger, one nurse almost got into a fight with the soldiers. The DPR people left and didn’t interfere anymore. They never showed up again.”

“Do you feel any anger towards the Russians?”

“Well, none of them did anything bad to me.”

“And who was responsible for the bombing of the maternity hospital?”

“I have no idea.”

Martyntsov was alone on the second floor and there the military behaved differently. The first thing they did was to search the wards and medicine boxes.

“I knew what they were looking for - drugs and psychedelics substances. It was obvious given how they read the labels on the packaging what they needed. They were experienced drug users. They opened all the safes, ripped off the doors and searched everything.” They didn’t find anything, as the surgeons had hidden all the drugs.

“But one took the new printer. It was so insulting - we had bought it at our own expense for the hospital. Then I saw the soldier: pot-bellied with a long uniform, dragging our printer under his arm. I don't know why he would need a printer in the middle of a war…”

The DPR detachment set up headquarters in the surgical wing.

One of the battalion commander assistants immediatelystarted drinking. ”I guess he was celebrating the victory.” He pulled out a gun and “demanded a woman.” Luckily, the surgeons had already taken measures to protect the women, and had hidden them in the basement.

Some of the other DPR soldiers came to deal with him. “They started chasing after him, but he understood that they would beat him up if they caught him, so he ran off somewhere at nightfall. The soldiers tried to find him, but he had disappeared. As we were right on the front line, they decided to wait until morning to find him. In the morning, they found him on a stretcher next to the mountain of corpses at the hospital’s main entrance. He’d slept on this stretcher all night without freezing - can you imagine how much alcohol he must have drunk?“

Evacuation at last

On 23 March, soldiers came to the basement where Dr Arkhipova was looking after the babies, and started searching the place. She told them that the Ukrainian military was no longer in the hospital’s vicinity. “We told them, what do we do? Our children are dying here?” Two days later they were offered an opportunity to evacuate. “If you want, you can run to another street at your own risk. There could be transportation. We advise you to leave sooner, as it will only get worse.” The doctors gathered up the children and under bombing ran to where a bus was located. The wounded mother of one of the babies stayed behind in the surgical building, as it wasn’t possible to transport her.

The doctors and children were taken to a village 20 kilometres outside Donetsk. They were fed, and the newborns were taken to the Donetsk city hospital. Later, the mother who was left behind, was also taken there and reunited with her baby. The head of the local paediatric department took the doctors to her own home. From there, the doctors left for other places.

Arkhipova went to stay with relatives in Russia near the Volga River. She has now requalified to practice as a doctor in Russia, having passed her exams with excellent marks. In theory this means she could start working in Russia or she could return to work in Russian-occupied Mariupol.

Like many residents from Mariupol who were evacuated to Russia, Arkhipova says she is worried that if she returns to Ukraine she will be accused of collaborating with Russian forces.

“I can't go back - they'll put me in jail and give me 12 years,"she says. After all, I am a medic, and as such could be called up to serve in the army. And I left the country to go to Russian territory.”

In fact, Dr Arkhipova is wrong on both accounts. As a neonatologist she would not be liable to be called up to join the army medical corps. And as the Ukrainian Health Minister made clear last August, Ukraine does not consider doctors working to save lives in occupied areas as ‘collaborators’. It is recognised that they are carrying out their duty to treat people, and nthey would not be subject to criminal prosecution.

Ukraine’s security services say only people who have taken up official positions in government structures established by occupying forces would be liable for prosecution.

Despite everything she has lived through, Dr Arkhipova refuses to put the responsibility for the tragedy of Mаriupol on one particular side.

“Do you feel any anger towards the Russians?”

“Well, none of them did anything bad to me.”

“And who was responsible for the bombing of the maternity hospital?”

“I have no idea. I was sitting there for a month feeling completely useless, and now I'm a national traitor. They still need medical workers in Mariupol.”

It is difficult to say whether she is saying this from a genuine belief, or whether being in Russia has influenced how she now thinks, or is able to talk about what happened to her there.

What happened next

Almost everyone who spoke to the BBC for this article has now left Mariupol, and only one person has returned. People’s memories of what happened in Hospital No. 3 and how they think about it now has been shaped by how they left the city, and what has happened to them since. For some, war is now a part of the past, which they are trying to forget. For others, it is still part of everyday life and something they are continuing to try to survive.

Elena Kramina and her family left via the DPR and Russia for Finland. They are not planning to return, as they have no friends or work opportunities left in Mariupol.

“On Ukrainian-controlled we would be afraid of coming under attack again and of course I’m also scared that my husband could be called up. I love Ukraine, but not enough to deprive my children of their father. Perhaps we’re not patriots...” she says. The relationship she has with relatives and friends who stayed in Russia remain unchanged. “I hate this war! I hate politics, but not people. I am against Russia’s actions - Russia is the aggressor here. But behind all of this is politics, power and money, and it’s the ordinary people who are suffering.”

Irina Solovyova along with her husband and children got to Krasnodar and they have decided to stay there. At first this was out of necessity, as their new-born daughter had no documentation, other than a tag from the maternity hospital on her leg. It took several months to obtain a birth certificate through a court in Kyiv.

The older child, a two-year-old boy, still needs medical care. During the shelling, he stopped talking and he still wakes up more than 10 times at night sobbing and shouting “stop”. Everything the family had worked and saved for was lost in Mariupol. Although they don’t want to get Russian citizenship, they were issued with residence permits in the autumn of 2022.

They are not planning to return to Ukraine, and again - mistakenly, they are convinced they would face problems if they did.

“They call those who left Mariupol and survived, traitors to the motherland,” says Irina. The echo of Russian talk shows and news programmes is clearly evident in her words.

The Solovyovs were initially reluctant to speak to the media and they told the BBC they had never shared the story of what happened to them in Mariupol with anyone before.

Another survivor, Aleksandra, one of the nurses from the maternity hospital, also seemed to be channelling Russian propaganda narratives, when she spoke to the BBC about her experiences.

She is now in Russia, living with relatives in the city of Vladimir.

“I understand that language isn’t an issue for you in Russia and that it is easier to get documents to go there. But Russia bombed you. Do you not think that you have come to live in a country which has bombed you?” I asked her.

“I don't think of it in this way,” she replied. “My opinion is that both are good. Some had an order to take the city by any means, and they destroyed it. While others had an attitude that they did not take us into account. I've seen the guns of both sides in residential building courtyards.”

Aleksandra has already received a Russian passport and has got a job in a medical laboratory.

Dr Martyntsov’s war

Dr. Aleksandr Martyntsov stayed in Mariupol the longest of all. By mid-April 2022, he and his traumatologist colleague were the only two doctors left in the surgical department of Hospital No. 3. Both had nowhere else to go. Their apartments had been bombed and they had no families.

“We immediately decided that we would not leave until the last wounded person did. And there was nothing to go with - as soon as we went to work, we just stayed there. We only had 700 hryvnias (approximately £15) for both of us, with no other clothes or transport available. Where would we even go, Zaporizhzhia by foot?”

All this time, Martyntsov’s daughter, who lives in Kyiv, was looking for ways to get her father out of the city. In the end, they managed to agree with some people from Donetsk who came and picked him up on 17 April. By that time there were no patients left in the hospital. From Donetsk he went to Russia, and then on through Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and finally he made it to Kyiv, where he was reunited with his daughter. For him, the war with Russia is still raging. It hasn't ended or receded into the past.

Martyntsov’s colleague stayed in Mariupol. At the last minute, he’d decided not to leave. “My apartment was burned out, my car was gone, I had no money, I have no relatives on the other side, I have nowhere to go,” Martyntsov remembers him saying. He is still alive, and the two are able to contact each other, although due to fears for his safety, Martyntsov doesn’t write to him. He still wonders why his colleague keeps on working there: “The head doctor of the hospital is still there with a lot of other people continuing to work in the hospital. What to say about them? Are they collaborators? Of course they are.”

Martyntsov has stopped speaking in Russian. He calls those living in Russia “zombie people”, and is bitter about the country he now calls a '“terrorist state”.

“Since 1992, it has been an aggressive neighbour who wants to take our territories. This war would have started earlier, but Chechnya prevented it. Since 2014, Russia has been an enemy that attacked my homeland and started a war. I saw it with my own eyes. After 24 February, this is a country that deliberately targeted civilians, killing more than 100 thousand in our city and then completely burned it down. That's what Russia is now.”

In March 2023 the Ukrainian mayor of Mariupol, Vadim Boychenko said that around 120,000 people now remained in the city out of a pre-war population of nearly half a million. He said 150,000 people had been evacuated to the rest of Ukraine, and that a further 150,000 had moved either to Russia or to other countries.

According to medical sources, roughly 95,000 people were killed in the battle for the city.

The occupying Russian authorities have started rebuilding the paediatric, surgical and maternity wings of Hospital No. 3 . The work is being carried out by migrant workers and local construction teams. The bombed-out area in the hospital yard has been cleared. The bomb crater between the maternity wing and the oncology centre has been filled in. The new buildings are taking shape. Gradually the outward traces of the 9 March attack are being erased, but the longer term impact on the lives of all the people who were in the hospital that day, will be felt for years to come.

Read this story in Russian here.

Edited by Jenny Norton.

Translated by Pippa Crawford and Patrick Harrison.

Illustrations by Tatiana Ospennikova.

BBC is blocked in Russia. We’ve attached the story in Russian as a pdf file for readers there.