Looking for my Ukrainian nanny

When the Russian invasion of Ukraine began Ibrat Safo's first thought was for Natasha, the Ukrainian nanny who had cared for him as a baby in Uzbekistan. After more than a year he finally found her.

By Ibrat Safo, BBC Uzbek.

“I was over the moon when I found out that you were looking for me!” Natasha says, her face beaming out of my phone screen. “Look at where you and I ended up!”

Natasha was my nanny when I was a small boy growing up in a remote town in the region of Khorezm in western Uzbekistan.

“You were such a disciplined boy, so well-behaved,” she recalls. “You’d fall asleep as soon as I’d start rocking your cradle. Do you still fall asleep so easily?” We laugh.

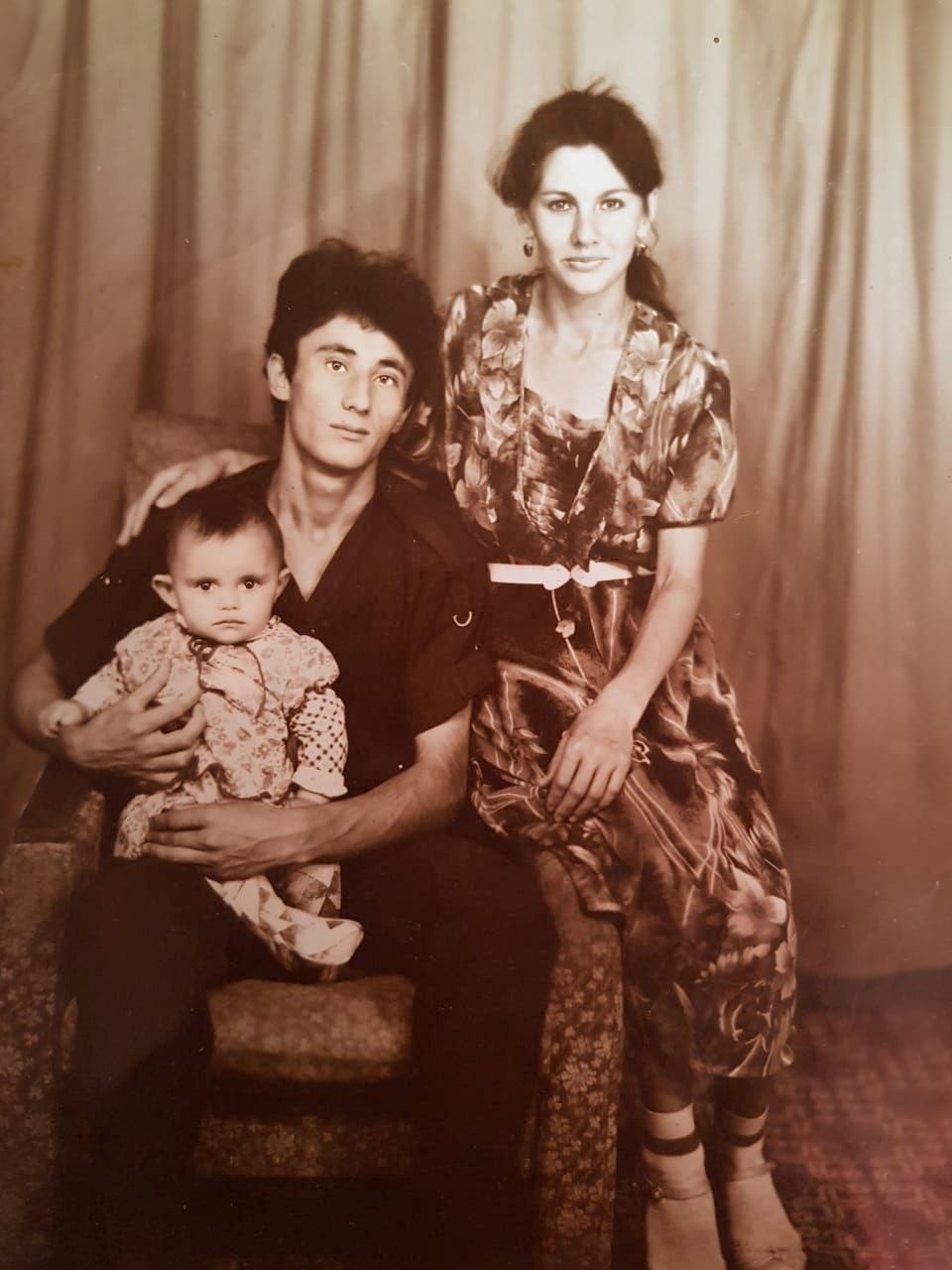

Natasha looked after me from when I was a toddler until I was about five years old – and that was the age I was when I last saw her. I still remember her pale skin and light brown hair and eyes, a visible foreigner in a land of dark-haired, dark-skinned Uzbeks. She was a teenager then. “I used to love looking after you,” she says. “I remember, I used to rush to your house after school – to me, you were like a cuddly teddy bear.”

Natasha went to the only Russian-language school in the small dusty town of Shovot where we lived – she taught me Russian words, which I’d then proudly repeat to my parents.

My mother and Natasha’s mother, Nina, had met at the local hospital where they both worked – my mother was a gynaecologist, Nina was a nurse – and the two women became close friends.

They used to walk home together after late-night shifts, and Nina would watch my mother climb over the garden wall so as not to wake the rest of the family.

Natasha laughs: “My mum used to wonder why such a respected family of doctors only had one front door key.”

Catching up after all these years, we’re talking in a mixture of the language of my childhood – the local Khorezmi dialect of Uzbek – and in Russian. But Natasha’s Russian is peppered with Ukrainian words and expressions – which was the language of her childhood.

Because Natasha is half Ukrainian. Natasha’s father, Matsapa, was an Uzbek who fell in love with her mother when he was doing his Soviet military service in Ukraine. This was in the early 1960s – we were all one big country back then, and young conscripts could be sent to any corner of the Soviet Union. When Matsapa returned to Uzbekistan, Nina went with him – and they married in Shovot, where Natasha was born.

As I grew up, our families lost contact. But I’d heard through relatives that Natasha had left Uzbekistan some years ago. Her husband had died in a freak accident, and she’d decided to go, with their two children, to her maternal homeland, Ukraine.

Which is why, when Russia invaded Ukraine last year, I had a strange feeling – an anxiety, as if someone very dear to me was in danger. That’s when I started my search for Natasha. It took me 16 months to track her down.

Social media didn’t help. My own family had moved away from Shovot long ago, so I asked anyone I still knew in town – childhood friends and distant relatives. All I remembered was that Natasha’s family had lived near the old hammam, the traditional communal bathhouse. The hammam was long gone too, friends told me. Eventually, someone passed my number to her cousin, who promised to put us in touch.

And that’s how I discovered that not only was Natasha not in Uzbekistan any more – but she wasn’t in Ukraine either. She was – wait for it – in The Hague! The very city where the International Criminal Court had issued an arrest warrant for the president of Russia, the country that had made her a refugee.

"I am waiting for Putin’s arrival with a traditional Ukrainian welcome of bread and salt,” she jokes – and we both laugh out loud.

I discovered that when Russia invaded Ukraine last year, Natasha had actually been out of the country – working abroad in Italy, as a carer. As soon as she heard the news of the war, she tells me, she immediately tried to go back to her home in the north-western city of Zhytomyr.

“I was worried about our house – I inherited that home from my grandmother,” she says, “and it is very dear to me. I wanted to be there to protect it.”

However, returning to Ukraine while war was breaking out was not easy. Natasha began her journey by bus, and was about to cross from Germany into Austria, when she was taken out at the border – not knowing any German or English, she still doesn’t know why.

She was held there for several hours, she says, until eventually the border guards let her cross into Austria. But she was still unable to find a route back home to Ukraine.

Eventually, her daughter – who now lives in the Netherlands – managed to persuade the Dutch authorities to let her mother join her there.

So that’s where she was when we at last spoke – Natasha in The Hague, and me – in London.

“I’m bored,” Natasha says. “It’s beautiful here – my daughter’s family, and her Syrian husband, are very welcoming. But I miss my home in Zhytomyr.”

But Zhytomyr isn’t safe. In the early weeks of the war, Russia occupied surrounding towns and villages and the city has been regularly bombed by Russian missiles – and is often left with little drinking water or electricity.

Natasha’s mood is more than just boredom, it turns out. She is actually very worried.

Her other daughter is still living in Zhytomyr. “She could leave,” Natasha tells me – her voice trembling a little.

“But her husband is of fighting age and must stay. So she’s sticking by him, with her four-year-old son – my grandson. I just don’t know where and when those wretched rockets will fall," she says.

My phone is heating up – we’ve now been video chatting for almost two hours. She still speaks perfect Uzbek, with the local Khorezmi accent we both grew up with.

“I have no home in Uzbekistan anymore,” Natasha tells me. “And just when I thought I had a home in Ukraine, I may lose that too.”

I try to console her. Don’t worry, I say: one day I’ll visit you in your home in Zhytomyr, and you’ll cook me a borscht – that wonderful steaming soup, red with beetroot, which I remember so well her mother making for us in my childhood.

"Of course!” she says. “And in the meantime, if you need a nanny for your kids, you know where to look."

We both laugh, but I know she is serious. She is still that beautiful and kind Natasha I remember as a boy.

This story was first broadcast on From Our Own Correspondent on BBC radio.

LONG READ. Trapped in Russia: How a three-week summer holiday turned into a seven-month nightmare for one Ukrainian schoolboy

By Svyatoslav Khomenko and Nina Nazarova. When Russian troops occupied the Ukrainian town of Balakliya last year, local children were offered the chance to spend a few weeks away from the fighting at a Russian seaside holiday camp. One of those who made …