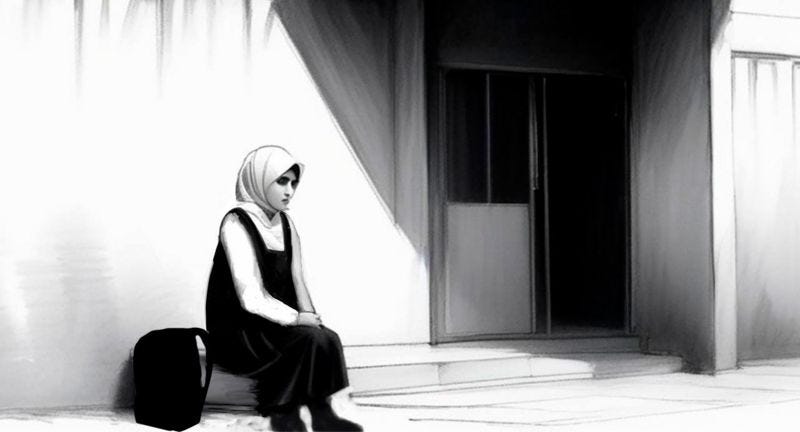

“My headscarf is simply a part of me”: the Kazakh schoolgirls fighting for the right to wear the hijab

The struggle goes to the heart of questions about the country’s post-Soviet identity.

By Aisymbat Tokoeva. BBC, Karaganda

Kazakhstan is one of the few predominantly Muslim countries which bans young women and girls from wearing the hijab at school. The restriction on religious head coverings was introduced in 2016, but is still argued about now, with some religious parents trying to defend the constitutional right of their children to go to school and be educated.

The debate reflects an ongoing search for identity in Kazakhstan: on the one hand, the country's leadership displays its commitment to Islam; on the other, it is still unwilling to slacken Soviet-era controls on religious activity.

At the age of 13, Anelya, a seventh-grader from Karaganda, fulfilled her dream - she got a place in the prestigious ‘Nazarbayev Intellectual School’, or NIS. It is named after the former president of Kazakhstan, Nursultan Nazarbayev, and Anelya’s dream was to follow in his footsteps and become the country’s first female president.

A tall, slim girl, Anelya did well in local and national academic competitions, getting the 16th best result out of almost 800 applicants. The NIS held out the promise of delving deeper into her favourite subjects. “We lived nearby, and I would stare out of the window, and always thought I would study at NIS," she recalls.

In August, she went along for preparatory classes, but on day one, her parents got a call to come over to the school.

"They told us that they have their rules,” explains Anelya’s father, Bolat Musin, a local entrepreneur. “'Your child won't be able to study with us,' they said."

The school authorities said the reason Anelya couldn’t take up her place was her headscarf, which she had begun wearing from the age of 13, in accordance with the Muslim tradition that requires girls to cover their heads on reaching puberty.

"When I wore my headscarf to NIS I didn't feel different to others - it's just an item of clothing, an accessory. It has no impact on my studies or relationships with other students. My classmates were fine with it," she says.

Kazakhstan has a majority Muslim population – the 2022 census revealed that 69% of Kazakhs identify themselves as Muslims. And the president, Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, openly expresses his commitment to Islam: he went on a pilgrimage to Mecca in 2022 and hosted an evening Ramadan meal for officials and public figures at his residence last spring. Yet constitutionally, Kazakhstan is a secular country.

Dozens of students like Anelya, along with their parents, have faced similar problems in Karaganda, an industrial city with a predominantly Russian-speaking population. In October, it was revealed that the parents of 47 schoolgirls there were facing civil suits for failing to carry out their responsibilities ‘as prescribed by the laws relating to education in the Republic of Kazakhstan.’

Parents are being held to account — with warnings, and then sometimes with fines — for violating the school uniform rules laid out in a 2016 Ministry of Education directive, according to human rights activist Zhasulan Aitmagambetov, who assists religious families in such cases. Specifically, the directive states that ‘the inclusion of elements of religious attire from any confession in school uniform is not permitted."

Bolat Musin says that after protests from him and his wife, and after the involvement of the police, the school authorities ‘relented’. Anelya was able to wear a headscarf to the first day of the school year on September 1st. But three days later, she and other girls in hijab were again denied entry – reflecting similar events in other schools across Karaganda.

For parents and human rights advocates, it is unacceptable that school officials are prioritising a ministerial directive above the Kazakh constitution, which guarantees citizens the right to free education in public institutions.

Anelya's father sought clarification from the prosecutor's office and the Ministry of Education. The ministry redirected his inquiry to the local administration, which responded by saying that the Nazarbayev Intellectual School does not fall under their jurisdiction, and therefore they have no influence over it. Yet the NIS is governed by a board of trustees which includes government officials, and receives state funding.

The prosecutor's office directed Musin to the local police department, which wrote down his statement, but the case went no further.

Such cases, where parents are punished for their daughters wearing headscarves, go back years and cover the whole country. In 2018, in Aktobe region, parents were fined for ‘non-compliance with school uniform requirements’, while in Akmola region, a commission was convened at the district administration to address a similar issue the same year.

"There are many cases where girls take off their headscarves under pressure of the school authorities," says Zhasulan Aitmagambetov. "A few resist, but stop attending classes. The pressure is a way of reducing the number of religious believers in schools."

Kazakhstan’s government emphasises the secular nature of the state – also guaranteed by the constitution - when addressing the question of headscarves in school.

"We must always remember that school is primarily an educational institution where children come to acquire knowledge," stated President Tokayev in October. "I believe it is better for children to make their choices once they have grown up and have their own worldview."

But ‘secularism’ is poorly defined in Kazakh law. "Things are difficult here. On the one hand, there is the constitution that enshrines the right to education and the right to freedom of conscience," says Yevgeny Zhovtis, the head of the Kazakhstan International Bureau for Human Rights.

"At the same time, there is the principle of secularism and the risk of restricting rights and freedoms. Of course, any such constraint of rights should at least be covered by the Law on Education, rather than by a ministerial order."

"There is no unambiguous and concrete definition of the meaning of a 'secular state', either among the authorities or among experts," notes Asyltay Tasbolat, a religious studies scholar and research fellow at the Institute of Philosophy, Political Science, and Religious Studies in Almaty.

"Our society has not matured yet, and each side to the debate interprets ‘secularism’ in its own way. Some citizens understand secularism as atheism."

Several countries have introduced restrictions on the wearing of certain types of Muslim women’s clothing in public spaces. Usually, it applies to face-covering veils, such as the niqab, rather than head coverings like the hijab. It is rare for Muslim-majority states to institute such bans, but such nations include Kazakhstan’s neighbours, the former Soviet countries of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan.

The practice of keeping religion under state control has persisted in Kazakhstan since the collapse of the USSR. Back then, the five Central Asian republics were overseen by the Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Central Asia (SADUM), established in 1943, and designed to suppress religious movements. It was packed with ‘red mullahs’ who served in the KGB and were closely tied to the interests of the state, according to religious scholar Asyltay Tasbolat. One of the first ‘fatwas’ issued by SADUM, he notes, was to proclaim jihad against Hitler’s Nazi regime.

After independence, the Kazakh authorities ceased persecuting believers. Religious associations flourished and mosques began to be built: from a few dozen in Soviet times, there are now almost 3,000 of them.

As for the believers themselves, a 2021 survey commissioned by the Kazakh Ministry of Information found that the vast majority of the country's residents – 89.2% – identified themselves as adherents of one religion or another. That said, around two thirds said their faith was limited to religious formalities and holidays, and only 27.4% considered themselves deeply observant.

SADUM was replaced by DUMK - the Spiritual Administration of Muslims of Kazakhstan - a state-supported body tasked with promoting a traditional version of Islam that falls in line with Kazakh culture and the principles of a secular state.

For the Kazakh government, control over religion is a matter of national security. Researchers note that since 2005, under the influence of Islamist movements in the North Caucasus, the Afghanistan-Pakistan region, as well as Syria and Iraq, incidents of violence by religious extremists have been on the rise in the country.

In 2011, Kazakhstan saw its first terrorist attack since gaining independence: a 25-year-old man blew himself up in the offices of the National Security Committee in Aktobe region, injuring three people. In 2016, 25 people died in armed attacks on weapons shops and a military base. The then president, Nursultan Nazarbayev, declared the assailants to be adherents of the fundamentalist Salafi branch of Islam.

In the years following, the government implemented various restrictions in the sphere of faith, including a legal obligation to register religious communities with the state and a ban on conducting religious services in private homes.

But while the government justifies such measures as being in the interests of stability, security, and protecting the country from ‘radical’ religious ideas, human rights activists argue that the laws limit the rights of believers - and allow the state to stringently control religious association.

Last October, the government announced it intended to draw up a law against the promotion of terrorism and religious extremism. According to Aida Balayeva, the culture and information minister, the law would ban the public wearing of niqabs and other face coverings, in order to ensure individuals could be identified. She did say, however, that there was no intention to ban headscarves.

As for Anelya, after getting several reprimands for wearing a religious head covering, she was expelled from the school. Her father, Bolat Musin, appealed to the police and to lawyers, who recorded her exclusion from the educational system. Musin believes his daughter’s expulsion to be against the law: he has filed suits calling for the annulment of the school’s internal directives prohibiting the wearing symbols of religious faith, the reinstatement of his daughter Anelya, and compensation for moral damages.

"The authorities either kicked us from one bureaucratic body to another, or just said take the headscarf off," he says. "Now we are trying to resolve this issue via legal channels —through the courts. We need a clear answer from the state. Give us guidelines on what we, as religious individuals, should do,” he says. “Don’t leave us this choice: 'Abandon your religion, if you want to live in our society.'"

The NIS school authorities in Karaganda declined to comment on Anelya's expulsion. At the time of publication, the Ministry of Education had not responded to the BBC’s questions.

The state religious body, DUMK, expressed itself with caution, not directly criticising the government's prohibitions but noting that Sharia law requires girls to wear the hijab once they have reached puberty. It said it hoped the government would take their views into account.

Human rights activist Zhaslan Aitmagambetov says that religious families in Karaganda have no option for educating their girls. Such parents, he says, would willingly send them to study in a religious school, where they would feel comfortable, but no such educational institutions exist locally. In other parts of the country, there are paid, private girls’ schools, but they cost up to 700,000 tenge a year – more than $1500. Kazakhstan also has nine madrasas – Islamic centres of learning – but not all of them admit females.

“We have been raising this issue repeatedly, this year and last. They talk about the headscarf ban, but don’t offer an alternative means of education,” says Aitmagambetov. “We appealed for online tuition – if you don’t want to see us, religious parents and children, educate us online. They refused.”

Following her expulsion from NIS, Anelya’s parents found a Russian-speaking tutor online. But if Anelya decides to remove her scarf in order to return to school, her father says the family will support her.

“Lots of people I know said ‘take off the headscarf, what’s the big deal? Go back to school, especially considering how good it is’,” says Anelya. “But it never occurred to me. My headscarf is simply a part of me.”

BBC is blocked in Russia. We’ve attached the story in Russian as a pdf file for readers there.

Illustrations by Magerram Zeynalov, BBC.

Read the full story in Russian here.

English version edited by Chris Booth.

“I am Kazakh”: How one Central Asian nation’s new generation is turning away from Russia

Since the start of Russia's war in Ukraine, there is growing talk of "decolonisation" in Kazakhstan, Central Asia’s largest country. But what does it mean?

The January that changed Kazakhstan: How the country is surviving the aftermath of the largest riots in its history

A year on, there is still no convincing explanation as to how and why the riots unfolded. We spoke to those who survived the January 2022 events in Kazakhstan.