‘Not treason but a fight against evil.’ How one Russian couple helped the Ukrainian war effort

Sergei and Tatyana Voronkov left Russia in 2014 after growing disillusioned. But when Russia came to the Ukrainian village where they had resettled, the couple knew it was time to fight back.

By Ilya Barabanov and Anastasia Lotareva.

When Sergei and Tatyana Voronkov moved from Russia to a small Ukrainian village, they were hoping for a quiet life.

Things turned out very differently.

After Moscow launched its full-scale invasion, the anti-Kremlin couple found themselves in occupied territory and decided to become informants for the Ukrainian army.

What followed was detention, interrogation, and an escape into Europe involving forged documents - and a rubber ring. The BBC heard their story.

Sergei and Tatyana Voronkov made the decision to leave Russia shortly after the annexation of Crimea and the start of fighting in eastern Ukraine in 2014.

“We were going to protests…but we soon understood it was useless,” said the now 55-year-old Sergei.

“I would tell friends and acquaintances that it was bad we had taken Crimea and were getting involved in the Donbas. There was more and more negativity from people, they would say that if we didn’t like it we could leave. So we decided to go.”

Tatyana, 52, who was born in the Donbas but like her husband is a Russian citizen, said she started experiencing problems at work around that time. Her colleagues disliked her political views and she ended up leaving her job.

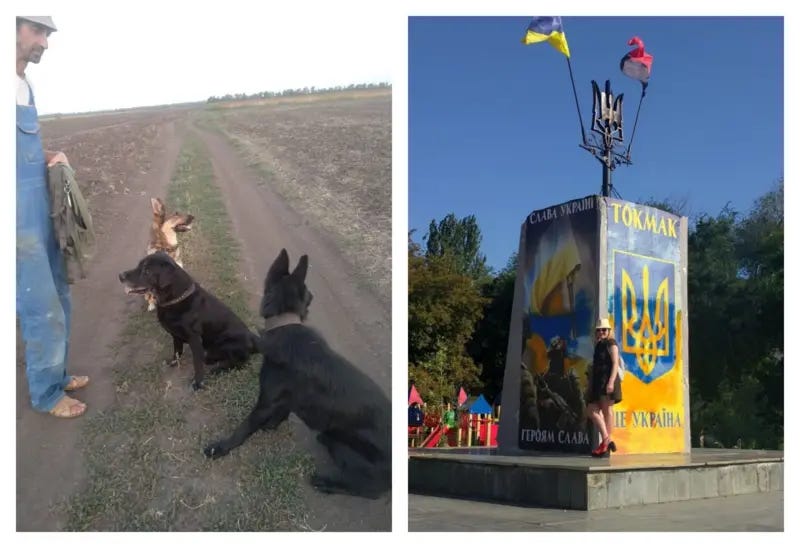

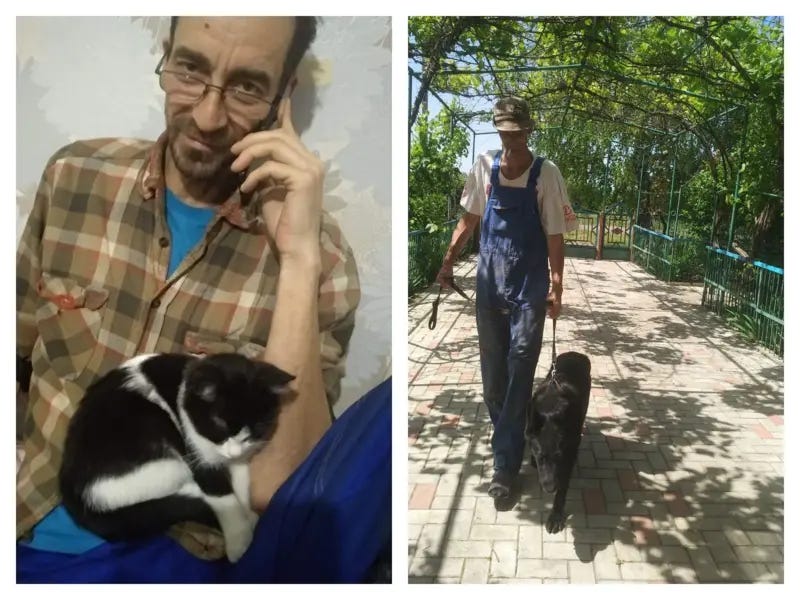

From 2016, the couple would go to Ukraine every six months, looking for a place to live. In 2019 they settled in Novolyubymivka, a village of some 300 people in the southeastern Zaporizhzhia region, where they raised livestock. Sergei also found work as a land surveyor, a field he had specialised in during his time in the Russian army.

On 24 February, 2022, the first Russian rockets flew over their home.

Contact with Kyiv

By 26 February, Novolyubymivka, like almost all of the south of the Zaporizhzhia region, was under Russian occupation. “For quite a long time we were living in a ‘grey zone’. Troops came to [the nearby city of Tokmak] but they didn’t stop where we lived,” said Tatyana.

But a military convoy passed by, and when it did, the couple decided to report it.

“We’ve always been on the same wavelength,” Sergei said. “We’d been told once before to leave, and we left. The second time they came, we thought: are we actually going to leave again?”

Seeing the passing convoy, Tatyana ran inside, grabbed her phone and wrote to an acquaintance in Kyiv, whom she believed had contacts in the Ukrainian security services.

The acquaintance sent her a link to a special chat-bot on the messaging app Telegram. The chat-bot informed them that they would be contacted by a person with a unique identifier.

The couple were asked to provide the location and details of electronic warfare systems and military hardware that they saw - with particular attention to be paid to missile systems and tanks.

“We didn’t think of it as treason,” said Tatyana, despite the two of them being citizens of Russia. “It would be treason if Russia were attacked and we were working with the enemy. But nobody attacked Russia. This was a fight against evil.”

The couple insisted that the information they passed on did not result in any strikes on civilians or civilian infrastructure. “There was an instance where there was a big, juicy target [nearby, but the Ukrainian military] said: we’re not going to hit it, we’ll get people’s homes,” Sergei said.

For two months, Sergei would collect coordinates and Tanya would transmit them from her phone, carefully removing all traces of the messages afterwards. The couple was in touch with their curator in Kyiv until the end of April 2022, when Novolyubymivka lost its internet coverage.

By then, armed men without insignia were constantly coming to the village, entering and searching properties. They visited the Voronkovs several times.

Asked why they did not simply leave the occupied territory, the couple responded: “Where would we go?”

They did not want to return to Russia. They would not be allowed into Ukraine with their Russian documents. Above all, they “felt at home” where they were and wanted to continue helping Kyiv in the war effort.

All that came to an end with Sergei’s arrest.

The pit

As citizens of Russia, the couple attracted attention from Russian security officers from the start of the occupation.

“We were under suspicion straight away,” Sergei said. “We were always being asked: ‘What are you, as Russians, doing in Ukraine?’”

Towards the end of April last year, Sergei was in the regional centre of Tokmak when he was approached by armed men without insignia. The men took him to a house and put him in a basement pit, which Sergei believed would have been used to store vegetables before the occupation. He estimated the size of the hole at around two metres wide and three metres deep.

The pit was cold and he slept in a squatting position, Sergei said. The following day he was taken to an interrogation with a bag over his head. Officers asked whether he had passed on details of Russian positions to the Ukrainians.

On the first day, he denied any involvement. On the second, he was subjected to a lie detector test - still with a bag over his head. On the third day he said he was told: “Confess. We’re being nice with you, but we don’t have to be.”

Sergei said that he was not beaten but he was threatened with violence. Unable to see, he expected the blows to come at any time.

On the fourth day he made a confession, worrying that if he were subjected to violence he might accidently implicate others.

All the while, Tatyana was desperately trying to find her husband. She travelled the area and called in on morgues and hospitals. She wrote to the police about her husband’s disappearance. Their son, who was still living outside Moscow, began to contact various authorities in Moscow - from the Investigative Committee to President Putin.

On the tenth day after the arrest, security forces came to Tatyana in Novolyubymivka to conduct a search. They dug up 4,400 dollars from the garden - savings that had been hidden by the couple.

Only on 7 May did Tatyana get an update on her husband’s whereabouts. “In Tokmak the police told me: ‘He’s sitting in a basement. The FSB took him. Counterintelligence.”

Sergei continued to be held in the pit. He was not allowed to wash, was given very little food, and his captors refused to answer his questions. On 26 May, people who introduced themselves as FSB officers arrived and recorded him giving a confession on video.

Two days later he was unexpectedly released.

The men who had taken him kept almost all his documents, returning only his driving licence.

Sergei and Tatyana to this day do not understand why he was released after he had made a confession. “Maybe, they needed hard evidence, and apart from what he had said there was nothing,” Tatyana said.

Escape with a rubber ring

Sergey went to the passport office in Tokmak and applied for replacement documents. But officials were in no hurry to issue him with a new passport.

The couple noticed that different cars were constantly driving by to check on the house. Often unknown people would come to the door to ask if they were selling anything.

The pair knew they would not be left alone. After consulting with human rights activists based in Europe, they decided to get out of the occupied territory - first by returning to Russia and then leaving to Europe from there.

“When we said we were going to leave, the neighbours helped and bought a lot of the livestock and farm equipment,” Tatyana said. The couple even managed to find a new home for their dogs, Sergei said, which was his biggest worry.

“The military moved in two weeks later,” Sergei said when asked what happened to their house afterwards.

To get out of Novolyubymivka without being stopped, the Voronkovs decided to make up a cover story about going to the sea so Tatyana, who has asthma, could get some fresh air. They loaded up their car with beach equipment, like a wide-brimmed straw hat and a rubber ring.

And at first they really did go to the sea, stopping for a night at Berdyansk, a port city under Russian control. After a night they continued on to Luhansk, near the eastern border of the occupied territories.

But when they tried to pass into Russia they were told that a photocopy of Sergei’s passport would not be enough to get them through. They had to go to another city for a certificate proving that Sergei had applied for a new document. The following day, they were allowed out of occupied Ukraine.

Family split

When they arrived in Russia, there were further delays in getting Sergei the full passport that would have allowed them to travel into Europe.

In September last year, they tried to leave Russia via Belarus without documentation, but were stopped by police. When officials checked a database, they saw that Sergei had previously been arrested and said that the local FSB would come to question him.

To the couple’s surprise, the local FSB officers released them and simply said they needed to apply for a new passport.

Sergei instead bought a fake passport, bearing his own name, through Telegram. The couple were then able to travel to Belarus and from there cross into Lithuania.

But border guards in Lithuania discovered Sergei’s documents had been faked and put him in a pre-trial detention centre.

Sergei did not find the experience unpleasant.

“After everything else I’ve been through, it felt like being in a guest house - just one that you can’t leave,” he said. “You get to wash twice a week. The beds are changed regularly and the food is fine.”

A Lithuanian court found Sergei guilty of using a fake passport and sentenced him to 26 days, which he had already served in pre-trial detention.

The couple hope to receive asylum in Lithuania.

The Ukrainian army sent a letter of thanks to the Voronkovs, at the request of their former handler in Kyiv, to support their application for asylum. The BBC has seen a copy of the letter.

Sergei’s 87-year-old mother still lives in Russia. She holds opposing views to her son, and at the start of the full-scale invasion they argued and stopped talking for a period. The Voronkovs’ son, who also remains in Russia, stopped communicating with his parents after learning what they had done.

Despite these family connections, the couple are adamant they will never return to Russia.

“Only if it starts showing some humanity,” Sergei said. “For now, I see nothing human there.”

Read this story in Russian here.

English version edited by Theo Merz.

"If you don't admit what you've done, your child is going to an orphanage"

To break her will, a Russian political activist is deprived of her disabled son.

Brave couple. Glad they could get out.