'Just a rogue pawn'- the rise and fall of pro-war anti-Putin nationalist Igor Girkin

Igor Girkin, the Russian nationalist and former FSB officer, who spearheaded Russia's invasion of Eastern Ukraine in 2014, now finds himself in trouble for being too critical of the Kremlin.

By Sergei Goryashko, Elizaveta Fokht, Ilya Barabanov, Amalia Zatari, Anastasia Golubeva.

Igor Girkin, the ultra-nationalist pro-war blogger and vocal critic of Vladimir Putin has been been arrested in Moscow on charges of extremist activity. A former FSB officer who played a key role commanding pro-Russian rebels in eastern Ukraine in 2014, Girkin was previously seen as untouchable. In 2022 a court in the Hague convicted him of murder for his role in the shooting down a Malaysian Airlines’ passenger plane over Ukraine in 2014.

Igor Girkin - known in Russia by his nom de guerre Strelkov is a vocal supporter of Russia’s war in Ukraine, but he’s become an increasingly vocal critic of the way the war is being fought.

In excoriating posts on social media he has regularly lambasted both Russia’s military top brass and commander in chief Vladimir Putin himself.

On 18 June he described “the person running the country” as a “nobody” and a "cowardly cretin,” reserving further insults for Putin’s entourage and the Wagner Group.

While followers of his posts would argue that this kind of rhetoric was nothing unusual for Strelkov, it clearly crossed a line somewhere and on 21 July he was arrested at home on charges of “carrying out extremist activities via the Internet”. The offence carries a prison sentence of up to five years.

Strelkov’s lawyer says his client admits “expressing his opinion about problems linked to Crimea and the fact that the paratroopers of the 105th and 107th regiments have not been paid”.

Strelkov has been remanded in custody at Moscow’s Lefortovo prison until 18 September awaiting trial.

BBC is blocked in Russia. We’ve attached the story in Russian as a pdf file for readers there.

Start a war, shoot down a Boeing, win a medal

Born in Moscow in 1970, Igor Girkin began his career in academia - аs an avid student of military history. But in the 1990s he swapped the study of war for the real thing, fighting in Moldova’s pro-Russian breakaway region of Transnistria, and then later in Bosnia.

According to his official biography, after completing his military service he stayed on in the army as a contract serviceman, serving in the First Chechen War, and eventually joining an FSB special forces unit. He fought in the North Caucasus, retiring in 2013 with the rank of colonel.

In January 2014 at the height of Ukraine’s Maidan protests (known in Ukraine as the Revolution of Dignity) Strelkov turned up in Kyiv. Officially, he was acting as security guard for the ‘Gifts of the Magi’, holy relics on loan to Ukraine from Mount Athos. He was working at the time for Konstantin Malofeev, known as Russia’s ‘Orthodox Oligarch’ and proprietor of the ultra-patriotic Tsargrad TV channel.

In March 2014, Strelkov played a role in the Russian annexation of Crimea, and in April he and a small detachment of fighters captured the Ukrainian city of Sloviansk, in Donetsk region. For three months the city became the focal point of fighting between pro-Russian forces and the Ukrainian army until it was retaken by the Ukrainian side in July 2014.

The fighting for Sloviansk fuelled the wider conflict in eastern Ukraine, as Strelkov later boasted to the Russian outlet ‘Zavtra’.

“I pulled the trigger,” he said. “If our squad hadn’t crossed the border, it would all have been over, just like in Kharkiv and Odesa. A few dozen people would have been burned, killed, arrested. And that would've been the end of it. But the war is still going on, we set the wheel turning.”

In the first weeks of the occupation of Sloviansk, Strelkov stayed hidden behind his balaclava. But on 26 April 2014 he gave his first interview and became an instant hero to the pro-Kremlin media.

The fighting for Sloviansk came to an end on 5 July 2014. Strelkov had demanded more armour and shells from Moscow – as Yevgeny Prigozhin was to do during the battle for Bakhmut in 2023. But unlike Prigozhin, Strelkov didn’t hang around waiting for the deliveries to come. Instead he decamped to Donetsk with his fighters, where he proclaimed himself Minister of Defence of the so-called Donetsk Peoples’ Republic, DPR.

The MH17 tragedy

On 17 July the fighting in eastern Ukraine, took an even darker turn when Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 en route from Amsterdam to Kuala Lumpur was shot down over Donbas, killing all 298 people on board. Most of the dead were Dutch, Malaysian, and Australian citizens.

Strelkov and his fighters denied any involvement.

“The militia never shot down that plane.” he said.

But on the day of the disaster, a post had appeared on Strelkov’s Telegram channel – showing footage of the smoking wreckage of a plane, with the caption: “They were warned not to fly over our skies.”

The post was quickly deleted when it became obvious that the plane in question was a civilian airliner.

In November 2022, after a six-year international investigation and a trial lasting more than two years, a Dutch court in The Hague concluded that the plane had been shot down by a Buk missile, launched from a farm near the town of Snezhny, in Donetsk region. It found three defendants – Strelkov, his deputy Sergei Dubinsky (call sign ‘Gloomy’) and Leonid Kharchenko, a Ukrainian citizen, all guilty of murder and all three were given life sentences in absentia.

A month after the shooting down of Malaysian Airlines plane took place, Igor Strelkov returned to Russia. The Donetsk ‘Peoples’ Republic’ was to have a new leadership. Both Streklov and the DPR leader Aleksandr Borodai - a Russian political strategist, were replaced by local men.

Strelkov and Borodai were old friends, but after their return to Russia they fell out. Borodai stayed loyal to the Kremlin, giving regular interviews to state media, and even becoming a Deputy of the Duma, the Russian Parliament. Strelkov took a much more critical line, and Russia’s state-controlled TV channels stopped mentioning him.

Back in Moscow

Back in Moscow, Strelkov set up a charitable fund for former fighters. Based in a suite of rooms in a lavish building by the Taganskaya Metro station, he decorated his office with portraits of Putin and Tsar Nicolas II.

In 2017, Strelkov publicly debated with opposition leader Alexey Navalny, a figure he’d always clashed with. The pair both criticised the government, but from very different perspectives.

Since the start of the Russian invasion in February 2022 Strelkov has made several attempts to return to fight in Ukraine.

In August he was stopped in annexed Crimea, trying to sneak into the war zone. He’d shaved off his moustache and was using a passport under the name of ‘Sergei Runov’.

“I’ll get to the front sooner or later,” promised Strelkov, who denied being detained.

His last documented attempt was back in October. After a few months away from the public eye he resurfaced on social media, in snapshots presumably taken at the Ukrainian border near Rostov. But by December he had admitted defeat and announced that he returned to Moscow.

"Gilded chickens and clowns”

Keen not to lose the public profile which war in the Donbas had given him, Strelkov has made big efforts to boost his image on social media.

By the time of his arrest, his “Strelkov Igor Ivanovich” Telegram channel notched up 875 thousand subscribers – twice as many as that of RT chief propagandist, Margarita Simonyan.

Strelkov managed his own channels, but after his YouTube channel was blocked early on in the war he was forced to appear as a guest in the videos of other bloggers, and to try to establish himself on other platforms he was unfamiliar with.

As the war ground on Strelkov’s material was veering rapidly away not just from the narrative in the state media but also from what was being said by other pro-Russian, pro-war blogs. His criticism of the Russian authorities sometimes seemed to have more in common with Russian opposition or even Ukrainian channels.

Strelkov is, of course, not the only insider to criticise Russia’s ‘Special Military Operation’.

As the BBC has reported, there have been complaints about individual generals and tactics since Ukraine’s successful counter-offensive in Kharkiv. But Strelkov’s diatribes have taken a different tone.

In some of the milder epithets from the daily post on his Telegram channel, Strelkov has called Vladimir Putin the “Supreme Anti-Commander” dubbed Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu “the Plywood General”, dismissed Russian generals as “gilded chickens” and “clowns” and referred to various Russian officials as “our cretins”.

In Strelkov’s view, Russia’s weak military leadership has blundered its way through the war, failing to strengthen the border; while civilian officials have been unable to set the country on a military footing, endangering it with defeat and social collapse.

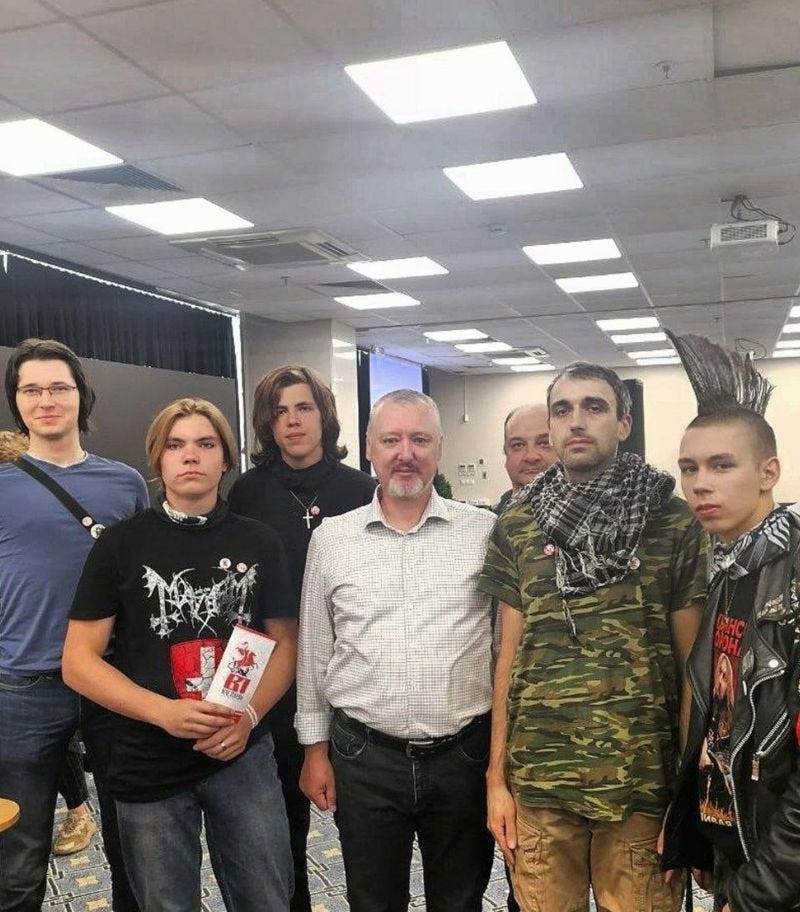

Matters escalated in the spring, when Strelkov founded the ‘Club of Angry Patriots’ [KRP] , with former Donetsk ‘governor’ Pavel Gubarev, as appointed Chairman.

Strelkov and the KRP threatened to meet the next serious crisis in Russia with “strong political force,” and called on Putin to resign if he was not ready to take responsibility for the war.

But its seems unlikely Strelkov could turn the KRP into a real political force.

Although he clearly has public recognition - a Levada Centre opinion poll in 2015 found that 27% of Russians had heard of him - another poll in 2022 found that only 0.4% of Moscovites said they would trust him “to the highest degree.” He was soundly beaten by both opposition leader Aleksey Navalny, on 2.6%, and Defence Minister Sergei Shoigu on 11.8%.

The patriotic public – already wary of Strelkov’s fiery rhetoric – started to condemn him for being too critical. State propagandist Vladimir Solovyov called him “a greedy bastard who couldn’t find his own ass in broad daylight.” He also described Girkin’s retreat from Sloviansk as “cowardly.”

In April, the Mash Telegram channel reported that legal action against Strelkov was pending – with his videos and alleged profiteering from the war to be used as evidence of his ‘discrediting the army’.

A lot of people were delighted. State Duma Deputy, Oleg Matveichev, said: “Strelkov just doesn’t understand what’s going on, he’s not seeing the higher strategy. He’s caught up in his tiny little mind, calling everyone else fools, slinging mud at them.”

A wrong way to support the war

Strelkov is not the first pro-war figure to be prosecuted for ‘discrediting the army’.

A few days before his arrest, it emerged that former military intelligence officer, Colonel Vladimir Kvachkov was facing similar charges.

Kvachkov, well-known for his antisemitic and radical views, has served prison time for organising a mutiny, and he continued to criticise the authorities after his release in 2019.

Whilst supportive of the war, he believes it has been handled badly. Even during the early phase of the invasion he was arguing that Ukrainian forces were superior in terms of both manpower and equipment, calling for "at least partial" mobilisation in Russia.

Partial mobilisation was introduced in September 2022 – but Kvachkov and Strelkov still weren’t happy. "We need general mobilisation, at least a million ground troops," said Strelkov, in an interview on state channel RTV1.

On 9 July, the police raided a St. Petersburg bookshop, popular with the far-right, and which openly fundraises for the army.

Strelkov was set to give a talk about the mutiny by the Wagner Group. After everyone in the shop was evacuated under the pretext of a bomb threat, the talk was moved to a “secret location.”

The bookshop’s Telegram channel reported that police had come calling the previous evening. All employees were forced to sign a disclaimer regarding the “misguidedness of actions creating conditions for the commission of crimes“.

As Strelkov’s speech was a public event, it had apparently required approval from the authorities.

Alexander Verkhovsky, director of the now-liquidated Sova analytical centre, says figures like Strelkov and Kvachkov evaded punishment for criticising Russia’s leadership for a surprisingly long time.

"It's incomprehensible – these people were using all kinds of language to slander the government, and nothing happened to them. Maybe someone just cracked after a year and a half.”

In Verkhovsky’s mind, the authorities have decided it’s time to crack down on the “ultra-patriots” .

"Kvachkov, Strelkov, and the bookshop in St Petersburg are all separate branches – the only thing linking them is a critical attitude towards the authorities,” he said. "That and nationalism. And it’s this combination that’s worrying the government – support for the invasion but not for the management. They’re having to tighten the screws.”

A pawn can be sacrificed

But not everyone was celebrating Strelkov’s arrest and prosecution.

The commentator Yegor Kholmogorov called him “a buffoon with past merits”, pressing the leadership to acknowledge this.

“It’s ridiculous to treat Strelkov as a dangerous political organiser," he wrote on Telegram. “Going after him as a politician will only increase his stake, which is currently very low. And prosecuting him would harm the cause.”

A former MP and air-force colonel Viktor Alksnis called the criminal case against Strelkov a "mistake" on the part of the authorities, which would “cost them dearly”. “Our government hasn’t been able to defeat Ukraine in battle and are now following the maxim: Attack your own to frighten the others!”

“I don’t think Strelkov is about to disappear,” said Aleksandr Khodakovsky, a Donetsk field commander often criticized by Strelkov. “But everyone is the architect of their own happiness – he’s responsible for all his actions and inaction, for everything he’s said, and all he’s left out.”

A former FSB colleague of Strelkov’s, who asked the BBC for anonymity, has been following his career with “ironic interest”. “He’s not about to turn into Mandela,” observed the official.

The BBC asked longtime Strelkov associate, Aleksandr Zhukovsky, whether the charges against him were linked to Prigozhin’s mutiny.

Zhukovsky said: “It’s true that Strelkov has kept up this critical position for years without anyone touching him. There was a rumour that Strelkov came to Moscow eight years ago, and started criticising [politician] Vladislav Surkov. In private, Surkov said that he was having to play on “eight chessboards at once” and Strelkov was “just a rogue pawn”.

“Prigozhin was more of a rogue queen,” said Zhukovsky, continuing the chess analogy, “You have to negotiate with a queen, whereas a pawn can just be sacrificed. And it turned out that removing Strelkov from the board was pretty easy. He doesn’t have troops or frontline support behind him to make trouble. And that was the difference – Prigozhin had a lot of resources. All Strelkov had was information and his network, and that’s not a problem for the authorities.”

Read the full story here.

Russian text edited by Anastasia Lotareva.

Translated by Pippa Crawford.

English version edited by Jenny Norton.

What Wagner mutiny means for Putin's Russia

By Amalia Zatari & Andrey Goryanov. The Wagner mercenary group's mutiny shows to the world that the key players in Russian President Vladimir Putin's autocratic system are no longer …

My role in the mutiny, by a Wagner fighter

By Anastasia Lotareva. Three weeks on from the Wagner group’s short-lived mutiny there are still more questions than answers about what exactly happened on 23–24 June, and what the future now holds both for the mercenaries, and their leader Yevgeny Prigozhin. Wagner fighters very rarely speak to the media, but BBC Russian reached out to one lower lev…