Faking the past: BBC Russian investigates a Soviet art collection that fooled the world

Paintings said to be by avant-garde masters were sold for hundreds of thousands of Swiss francs — and one was even featured in the film 'Oppenheimer'.

By Grigor Atanesian.

For lovers of one of the most dramatic episodes in modern art, it was nothing short of revolutionary: a collection of hundreds of hitherto unknown masterpieces by the leading lights of the Soviet avant-garde suddenly burst into public view in the mid-2000s.

Known as the Zaks Collection after its owner, some of the paintings from the trove were sold for hundreds of thousands of Swiss francs. A number of works were until recently on display in important American and European museums, and another appeared in two of Oscar-winning Hollywood blockbusters.

But a small group of experts had begun to suspect that the paintings might not be quite what they seem – and that the story behind the collection might be no more than a flimsy fabrication.

BBC Russian set out to find the collection’s mysterious owner - and uncovered a tale of greed, vanity and heartbreak that may have cast a lasting shadow over a unique period of visionary artistic experiment.

From the villages of Belarus to the auction rooms of Switzerland

In the early 2000s, an unknown private art collector turned up in Minsk, the Belarusian capital, with some good news to share: a vast collection of Russian avant-garde paintings had been discovered, and he wanted to exhibit them in Belarus.

There were more than 200 canvases in the collection, which included works by the great masters of the Soviet Union’s brief but explosive experiment in modern art: Kazimir Malevich, Alexander Rodchenko, Vladimir Tatlin, Natalia Goncharova, Liubov Popova, Alexandra Exter, Ivan Kliun, Robert Falk...

“This story is designed for people who are entirely detached from reality here.”

The mysterious owner was a Soviet émigré, Leonid Zaks, now a citizen of Israel. He claimed that his relatives had assembled the unique collection, receiving some of the masterpieces as gifts from Belarusian peasants and purchasing the rest either in state-run antiquarian stores in Moscow or Minsk in the 1950s.

The Belarusian cultural bureaucracy enthusiastically embraced the story and organised several exhibitions. "These are unique works, from which radiate warmth, kindness, and immediacy. We are very grateful to you for preserving them for us and for future generations," pronounced the country’s deputy culture minister by way of thanking Zaks.

But art historians were worried by Zaks’s single-minded avoidance of the National Art Museum of Belarus, by historical inaccuracies in the interviews he gave, and by the quality of the paintings themselves.

“This story is designed for people who are entirely detached from reality here,” said Alexander Lisov, a historian from Vitebsk, where some of the paintings were said to have been acquired.

Lisov drew attention to a mystery: the catalogue of one of the Belarus exhibitions indicated that the authenticity of the works had been confirmed by ‘N. Selezneva’, of the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. Yet no such employee had ever worked at the museum.

After this, there were no more exhibitions in Belarus, and an article about the Zaks Collection was deleted from Wikipedia. But this didn’t impede the collector: it simply shifted the focus of his activity. The exhibitions continued, but now they took place in the private Gallerie Orlando in Zurich. At least five major shows of the Zaks Collection were staged there between 2007 and 2014. As a commercial gallery, all the paintings on display were also for sale.

Most were bought by private collectors — sometimes for hundreds of thousands of Swiss francs. For one family, the purchases were to bring great sadness.

Art and the blind

When the legendary Zurich art collector, Rudolf Blum, lost his eyesight in 2005, his wife Leonor took over affairs. She started energetically buying Russian artworks through the Orlando gallery, trusting in its owner Susanne Orlando, and acquiring dozens of paintings for millions of Swiss francs.

Among the canvases were works by top-ranking avant-garde artists: Lissitzky, Rodchenko, Popova, Tatlin and Exter. One of the Lissitzkys was bought for 400,000 Swiss francs, and another for half a million. The painting by Liubov Popova was also purchased for 400,000 Swiss francs.

"[My mother] wanted to prove that she understood painting as well as my father, and she trusted Susanne Orlando," recalls Beatrice Gimpel McNally, the Blums’ daughter. "My father began to suspect something was awry, but what could he do?"

At the point at which she began to purchase the paintings, Leonor had already been diagnosed with vascular dementia. But when her daughter Beatrice shared her doubts with her mother, she not only dismissed them with indignation, but took deadly offence. The paintings damaged their relationship irreparably.

Beatrice’s suspicions were confirmed. After the death of her parents, the valuers of the estate said the paintings from the Zaks Collection were worthless. Auction houses in London refused to touch them, though one suggested she might contact James Butterwick, a British dealer and connoisseur of Russian and Ukrainian avant-garde art.

"The strength of the Russian economy"

James Butterwick’s Mayfair gallery specialised in ‘Russian and Ukrainian’ art up until 2022, when it changed its sign to just ‘Ukrainian’. The art remained largely the same.

Previously, ‘Russian avant-garde’ was the name given to work created in the early part of the 20th century by artists from Vitebsk in Belarus and Kyiv in Ukraine to Moscow and St. Petersburg. It included movements such as suprematism, constructivism, rayonism, cubo-futurism, and more.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, many people now prefer to use the terms ‘Soviet’ and ‘Ukrainian’ avant-garde art.

“The jeep was stuffed with literally tens of pictures, which to my eye looked completely wrong. And I asked him about it and he showed me various certificates of authenticity from a number of now former Tretyakov [gallery] curators. And I realised then that there was a major problem.”

Butterwick’s fascination with Soviet avant-garde began as an exchange student in the USSR, and culminated in his move to Moscow in 1994. It took him three days behind the wheel of his right-hand drive Citroen BX, with stopovers in Hanover, Poznan and Minsk.

With the demise of the Soviet command economy, the art market emerged from underground, and a wave of forgeries immediately washed over it. In those days, the early 90s, it wasn’t so much the mass production of fakes, but more an uncritical approach to old items.

It all changed in the 2000s when Russian capital broke from its native shores. In December 2004, more than a thousand paintings by Russian masters were presented at just two London auctions. Most were bought up by Russians.

Experts said the take-off in prices achieved by Russian painters reflected “high demand in Russia, and the strength of the Russian economy.” Before long, the avant-garde was leading the way, displacing academic painting. Interest in artists like Ivan Shishkin and Ivan Aivazovsky gave way to a stampede for canvases by Malevich and Kandinsky.

“The Russian bourgeoisie, as the pace of capital accumulation grew, began to try on the role of cosmopolitans,” recalls Mikhail Kamensky, an art historian and curator, the former head of Sotheby's in Russia, and deputy director of Moscow’s Pushkin Museum.

Working on forgeries

In November 2008, in the depths of the global economic crisis, Malevich's ‘Suprematist Composition’ sold at a New York auction for $60 million - a record-breaking sum for Russian art. Ten years later, the same painting would be sold for $86 million.

This rise in prices led to the emergence of an industry for the production and servicing of entire fake collections. Soon, police raids in Europe began to uncover warehouses with hundreds and sometimes thousands of paintings of inexplicable origin.

Butterwick recalls how once in Moscow, an acquaintance drove him in his “inevitably vast, great jeep.”

“The jeep was stuffed with literally tens of pictures, which to my eye looked completely wrong. And I asked him about it and he showed me various certificates of authenticity from a number of now former Tretyakov [gallery] curators. And I realised then that there was a major problem.”

He noticed that more and more of the suspicious paintings shown to him by his clients were accompanied by scholarly articles and certifications by experts in the field. Similar paperwork was attached to the works that Beatrice Gimpel McNally sought Butterwick’s advice on. Among it were the expert opinions of InCoRM, the International Chamber of Russian Modernism (pitching itself as an association of Russian avant-garde researchers) along with articles by the Belarusian art historian Tatiana Kotovich, and a researcher at the Russian Museum, Anton Uspensky. The Orlando gallery supplied the Blum family with translations as confirmation of the authenticity of the paintings.

Butterwick decided to dig deeper, and got in touch with his colleagues, Ukrainian curator Konstantin Akinsha, and St. Petersburg art collector Andrei Vassiliev. Akinsha had written an article titled ‘Fake’ for the New York magazine ARTnews as far back as 1996, in which he revealed dozens of works sold in error at European auctions as avant-garde masterpieces. It was the first investigation to show the scale of the problem the Russian art market faced. He has continued to consult on the matter – his advice caused the Museum Ludwig in Cologne to recognise many of its Russian and Ukrainian holdings to be forgeries.

Vassiliev is the author of the book ‘Working on Forgeries’, devoted to a portrait of Elizaveta Yakovleva, a well-known Soviet stage designer. It was exhibited as a previously unknown work of Kazimir Malevich by Britain’s Tate Gallery, at the ‘Worker and Kolkhoznitsa’ pavilion in Moscow’s VDNKh exhibition centre, and a number of European museums. It was put on sale for 22 million euros. Vassiliev proved, by archive research, that it was in fact by a forgotten artist from Leningrad, Maria Dzhagupova, and had first sold for a mere 14 roubles and 40 kopecks.

“What we have before us is a classic provenance myth.”

How to check a painting

The authenticity of paintings is traditionally established on three pillars: expert opinions, technical analysis, and provenance – the item’s history, in other words. Akinsha is the co-author of a textbook on provenance published by the American Association of Museums. He proposed getting to grips with the incredible history of the Zaks Collection.

According to Zaks, the collection’s founder was his grandfather, Zalman Zaks, a merchant and cobbler from Yekaterinoslav (present day Dnipro, in Ukraine). Zalman, so the story goes, became interested in radical art when he came across it in a Belgian bank in the town. He started buying up pictures.

The enterprise was continued by his daughter, Anna, who served as a military medic. At the end of the Second World War, she was treating patients around the Belarusian towns of Lepiel, Chashniki and Usachi. Newly-liberated from the Germans, the grateful peasants allegedly brought her works by El Lissitzky and Alexandra Exter, as payment for her services.

The story continues with Anna’s brother Moses, who was posted missing in action during the Second World War, and then resurfaced in 1950s Moscow as a US businessman. At the time, the Central Club of the Ministry of Internal Affairs was said to be running seminars condemning ‘formalist art’, following which the works of avant-garde artists were handed over to state-run antiquarian stores to sell.

Moses Zaks, according to the family legend, bought several dozen such masterpieces between 1955-56, and exported them all to Europe. There they remained until the 90s, when they were inherited by his nephew, Leonid Zaks, who worked in the oil industry in Moscow.

To prove his story, Zaks showed buyers a letter from the National Museum of History and Culture of Belarus, dated 2008, which recounted the entire history in detail - but with serious contradictions, strange typos, and outright errors. In this version, Uncle Moses disappears from the story, and it’s Aunty Anna who is the main collector of the paintings. And instead of the Interior Ministry in Moscow, the anti-formalist seminars are now said to have been held at the ‘Minsk City Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.’

When Andrei Vassiliev wrote to them, the National Museum of History and Culture of Belarus told him that “no such letter has been found in the museum archives.” The museum noted the reference on the letter, which was prefaced by an ‘M’. “We can report that when classifying outgoing letters in 2008, no ‘M’ was used before the number.” the museum said.

“So however you look at it, the letter is a fake,” Vassiliev says.

But the art detectives did not stop there. They carried out research in Russian and Belarusian archives and sent off dozens of requests to museums in an attempt to verify the key facts of the Zaks story. Russia’s interior ministry responded that no such events had been held in their club – for one thing, it had been closed in 1949 and did not reopen until 1966. As for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, they replied by saying that they had gone through their archive and had found no mention of the entry into the country by Moses Zaks during the years in question.

“We have checked the provenance of the whole of the Zaks Collection, and none of it stands up,” says Akinsha. “Or rather, we have been able to refute it. What we have before us is a classic provenance myth.”

In museums and Hollywood films

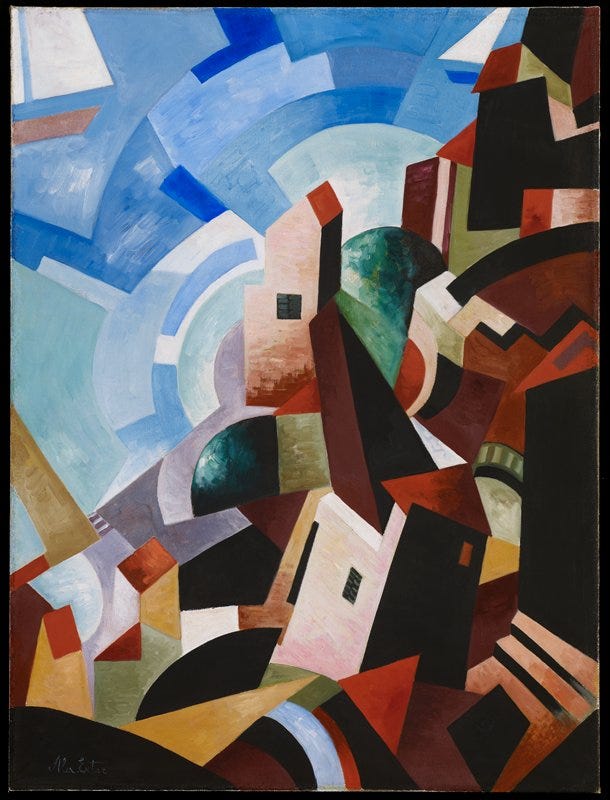

Two works from the Zaks Collection are housed in the Minneapolis Institute of Art. One, entitled ‘The Clockmaker,’ is purported to be by Ivan Kliun, and the other is by the Ukrainian artist Alexandra Exter.

‘The Clockmaker’ appeared in two of last year’s most successful films – Christopher Nolan’s ‘Oppenheimer’ and ‘The Wonderful Story of Henry Sugar,’ directed by Wes Anderson. Both went on to win the Oscars.

We got in touch with the Minneapolis Institute of Art about our verification of the provenance of the Zaks Collection. The museum promised to conduct its own investigation.

Soon after our letter, the painting was removed from display. And on the museum’s website the painting’s listing has changed and now says only that it is ‘attributed’ to Ivan Kliun.

Yet another canvas from the Zaks Collection, deemed to have been painted by the Ukrainian avant-gardist Alexandra Exter, is kept in the Cleveland Museum of Art. The museum curators were interested in the outcome of the BBC investigation but declined to comment.

We found another work from the collection, also attributed to Exter and titled ‘Genoa’, in the world-famous Albertina Gallery in Vienna. Representatives of the museum told the BBC that they had carried out their own checks on the painting and that it was not on display.

“It's like looking at something that should have been 18th century and there's a flat screen TV in the background. It's not possible.”

A flat screen TV in an 18th-century interior

Beatrice lent the BBC two of the paintings from the Zaks Collection that remain in her possession – an El Lissitzky ‘Proun’ (the name is an acronym of the Russian series title Project for Affirmation of the New) and Liubov Popova's ‘Painterly Architectonics.’

We transported the canvases from Zurich to London’s Art Discovery laboratory, where Dr. Jilleen Nadolny, a leading scientist in the field of the technical analysis of paintings, agreed to look at them. She has debunked dozens of Russian avant-garde forgeries.

Her analysis revealed fibres embedded deep in the paint of the Lissitzky painting. They had been treated with substances that were widely available only after the Second World War – and Lissitzky died in 1941.

“It's like looking at something that should have been 18th century and there's a flat screen TV in the background. It's not possible. You can't have it. It doesn't work,” Nadolny concludes. The painting is a forgery, she wrote, and came to the same verdict with the purported Popova.

"It’s all just based on words"

While the experts studied the provenance and examining the paintings, we went looking for those who had helped Zaks build a reputation for the collection - and wrote the scholarly articles that the Orlando gallery handed out to Beatrice's parents to convince them of the authenticity of the paintings being sold.

The only living art historian associated with a well-known public collection to have spoken positively about the Zaks Collection is Anton Uspensky, a senior researcher at the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg. He published three articles about it, including in prestigious journals such as ‘Art Dialogue’ of the Moscow Museum of Modern Art, and ‘Academia’, published by the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts.

The articles revolve around the alleged series of seminars against ‘formalism’, as mentioned in the Zaks family legend. But in conversation with the BBC, Uspensky said he never checked what Zaks told him. It was all just based on his words. “These are family recollections that have in no way been confirmed or recorded anywhere,” he said.

In one of his articles, Uspensky writes that “the historical and artistic value of the works has been confirmed by the expert opinions of specialists of international ranking.” The text is illustrated by photographs of the paintings, all of which are signed as original works by Rodchenko, Lissitzky and others, without the use of a question mark.

"What is a written is no longer a legend, it’s a fact. An incorrect fact, perhaps, but not just a legend or a story."

Nevertheless, Uspensky states that he did not confirm the authenticity of the pictures, and indeed had not seen a single one of them: he had only seen photographs of them, and was not aware that his name was being used to help sell the paintings.

In his articles, Uspensky also asserted that the Lissitzky ‘Proun’ from the Zaks Collection had been bought by the Kunstmuseum Basel. This is not true. “Having conducted an intense inspection of our archives, we have found no trace of the Zaks family, or of works related to them in particular,” the head of the provenance research department told us. The three ‘Prouns’ kept in the Kunstmuseum Basel hail from other collections.

The Vitebsk art historian Tatiana Kotovich also wrote extensively and with praise about the Zaks Collection. The BBC asked her about the role of her articles in selling the paintings. "It’s news to me. What you're talking about, the use of my name,” she said. “Nowhere does it say that I guarantee that this is indeed this artist."

Kotovich wrote that "Zaks has been collaborating fruitfully with prominent experts," and cited members of the InCoRM association of Russian avant-garde experts, who had issued certificates for many of the works from the collection sold by the Orlando gallery.

Soon after this, InCoRM found itself at the heart of two furores when certificates from its members surfaced in high-profile court cases in Germany and Belgium about forgeries of Russian avant-garde art.

Patricia Railing, the founder of InCoRM, told the BBC that the organisation had disbanded in the wake of attacks from critics: "With all these accusations of fakes and slander, nobody wanted to be engaged.”

Erroneous facts

All this time, we were trying to talk to Leonid Zaks himself. We wrote and called him at every possible address and phone number. His daughter forwarded him our request, but Zaks did not respond.

But two weeks before the publication of our story he suddenly got in touch, and agreed to a phone interview.

What was happening with the remainder of the collection that he had not managed to sell, and where was it now? Zaks was elusive: “I’d rather not go into this. Where is it? I’d like to avoid this and other questions, including questions about money. The collection is stored in a European warehouse.”

He denied any responsibility at all for the paintings sold on the European market. “I have been separated from these pictures from the moment they left the Orlando gallery. I don’t think these questions should be addressed to me!”

Time and again, he repeated “I didn’t sell anything [myself].”

So we asked him to talk about the provenance of the collection. What confirmation could he offer concerning peasants handing out modernist artworks in 1944-45?

"What kind of evidence? Have you any idea what it was like after the war?" Zaks responded.

He didn’t dispute that there had been no formalism seminars held at the Moscow interior ministry club, but simply referred to what a now deceased art historian had supposedly told him.

In response to the conclusions of the experts we had contacted, Zaks said it was his mother – “a very honest person” - who had written down the story of the collection. He added: “Well, whom should I trust, a bunch of strangers — or my own mother?”

I noted that his mother's story did not change the nature of his story - it's a family tradition.

Zaks replied: "What is a written is no longer a legend, it’s a fact. An incorrect fact, perhaps, but not just a legend or a story."

Zaks was less surprised by our questions about forgery and fabricated provenance, and more surprised by the sums Beatrice’s parents had paid for works from his collection. He declared that the works could not have been worth 400,000 Swiss francs, calling the sums “nonsense”.

“I have never clapped eyes on such money from the Orlando gallery,” he said.

Zaks was also upset that Uspensky did not defend the collection, and that the art historian said he had neither seen the paintings nor participated in their sale.

"Uspensky had been to the Orlando gallery, and more than once, by the way. And he saw what kind of gallery it was, and how it worked. He knew it was a commercial gallery, a kind of shop,” Zaks insisted.

“Destroying our own past”

At the very end of our conversation, I asked Zaks if he wanted to say sorry to Beatrice Gimpel McNally.

"I cannot apologise, but I can sympathise. There is nothing to apologise for," he replied.

Defrauded art collectors rarely draw sympathy from either art historians or the general public. They are, after all, wealthy people with cash to spare.

But in the case of Malevich, Lissitzky, Exter, Popova, Goncharova, and other masters of the avant-garde, it is no longer just a matter of the financial losses suffered by private buyers, but the threat to the artists’ entire legacy.

"There are many more fakes than authentic pieces," says Andrey Vassiliev. “The story of the Zaks Collection shows how easily dubious paintings with fabricated histories can find their way into the world’s leading museums. There they are seen by hundreds of thousands of people, they are printed on the pages of textbooks, and a new generation of art historians grows up with them.”

The prevalence of fakes is what motivates Akinsha, Vassiliev and Butterwick to fight back. But sometimes even they despair, admitting that the outcome of the battle is already well-known.

"Helped along by plenty of art historians posing as academic scholars, generously doling out certificates of authenticity for questionable works, [the Soviet avant-garde] has been turned into a giant hall of mirrors,” says Akinsha.

Despite many losses, the creations of the radical experimenters of their era – Russian, Ukrainian and Jewish artists – have managed to survive the depredations of the Soviet regime, the Second World War, and the Iron Curtain.

Decades of boom years for the market, and the wave of forgeries they provoked, now threaten to bury this legacy under a mountain of fakes.

The loss resonates far beyond the art world, and the rarefied class of well-heeled collectors, says Dr. Jilleen Nadolny:

“It’s a question of the interests of society as a whole. Taxpayer money goes towards acquiring exhibits for museums. Students come to lectures expecting to learn about authentic artifacts from a certain period and culture," she says.

“So there's so much damage that's done that is completely away from the lives of the rich people. And if we allow this to happen, we’re destroying our own past.”

The Orlando gallery did not respond to enquiries by the BBC.

Dr Jilleen Nadolny died at the end of 2023.

In collaboration with Tatiana Preobrazhenskaya and Tatsiana Yanutsevich.

English version edited by Chris Booth.

Read this story in Russian here.

Watch this documentary on BBC iPlayer.

The Largest Conspiracy in the Russian Art World:

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Soviet Union under the Bolsheviks enforced strict controls over cultural expressions, clamping down on abstract and avant-garde art, which they viewed as elitist and subversive. Such art was perceived as a threat to the new social order because it did not conform to the straightforward, propagandistic art that the regime favored. As such, thousands of paintings by prominent Russian artists like Wassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevich, and Marc Chagall were seized and stored in museums across Russia, often hidden, neglected, or poorly preserved, to suppress their influence on society.

In the early 1990s, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia faced severe economic turmoil and was on the brink of bankruptcy. The government was desperate to raise funds to stabilize the economy and provide basic services. As part of their efforts to generate revenue, they began to liquidate various state-owned assets, including real estate, hotels, and valuable artworks. Western art dealers and collectors were quick to seize this opportunity, often purchasing these valuable pieces at liquidation prices far below their market value.

A major buyer was Itzhak Zarug, who bought over 2000 paintings. Zarug emerged as a significant figure in the art market during the post-Soviet economic crisis. Recognizing the opportunity presented by Russia's need to raise funds quickly, he acquired several valuable artworks at relatively low prices. Unlike some who might have sold the artworks for quick profit, Zarug is noted for his efforts to preserve and promote Russian art. He often loaned pieces from his collection to museums and exhibitions, helping to raise awareness and appreciation of these works globally.

Another big collector of these Russian paintings was a prominent Russian art collector and businessman known for his extensive and valuable art collection.

While Itzhak Zarug became particularly active in the art market between 1990 and 2010, slowly selling the paintings at auctions at moderate prices, the Russian collector also began profiting from his paintings. He used his extensive art collection as collateral for financial dealings. This practice has included inflating the value of his paintings to secure larger loans, a tactic that allows leveraging his art assets for financial gain. However, the use of art as collateral is not without risks. The value of art can be subjective and fluctuates based on market conditions, provenance, and demand. Therefore, a problem did arise when finding out that Itzhak Zarug was selling the same paintings as him for a lesser price.

Another key detail was the era of Privatization in Russia during the 1990s that followed the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia aimed to transition to a market economy, which required extensive privatization of state-owned assets. A small number of individuals, known as oligarchs, amassed huge fortunes by acquiring formerly state-owned enterprises. This involved acquiring state assets at low prices through various methods, such as the loans-for-shares scheme or direct purchases.This concentration of wealth and power led to oligarchs like this Russian collector wielding significant political and economic influence during the 1990s. They often had close ties to political leaders and were able to shape government policies and decisions, and the Russian collector did indeed have those powerful connections in both the political world and art world.

The Russian collector recognized the problem with Itzhak Zarug selling his paintings at a lower price and realized he had to interfere. It was discovered that he had particular connections with a well known art museum in Russia. The museum has faced controversy in the past, like accusations of the museum making fake appraisals in the 90s. Regardless, the museum’s reputation remains unscathed and continues to be a powerful figure in the art world. Therefore, when the Russian collector collaborated with the museum to send a letter to German police accusing Zarug of selling fake paintings, the allegation was assumed to be true and Zarug was arrested. As such, in 2013 he was arrested in Germany on charges of selling forged Russian avant-garde paintings and all 1,800 of his paintings were seized. However, after 3 and a half years of investigations and many experts authenticating the paintings, 99% of them were found to be legitimate. Looking at the judgments, which can be found at the bottom of this article. In 2018, all Zarug collections were found authentic and he was able to resume selling his paintings as he pleased—or so he thought.

The Russian collector did not stop after putting an innocent man in prison, and he did not desire to stop as long as Zarug was interfering with his own sellings. With the museum, he bought two very large art magazines in New York and London and hired many freelance reporters to write critical articles on any activity regarding Zarug. However, it wasn’t just reporters. There was a gallerist in London who was found to be on the Russian collector’s payroll, and this gallerist badmouthed any painting from Zarug, under the pretense of being an expert.

Recently in January of this year, one of the paintings coming from Zarug was displayed in a private event at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. As usual, one of the paid freelance reporters engaged in the same fraudulent behavior and wrote an article on the event which he published in June, attacking Zarug, the painting, and the guests at the event. However, every line from that article was full of lies and fallacies. He had fabricated a story of the painting being fake when in truth the painting had passed all and any authentications required to prove genuinity. He published this report, along with many other critical articles through a very popular news publication without any genuine evidence. It is disappointing to see a news publication that is so prominent in the art world supporting such accusations without evidence, which leads to the question if the reporters are in cahoots with criminal wrongdoing, intending to ruin the reputation of an innocent man, or did they really just forget to fact-check such a critical allegation?

It is interesting to observe the lengths man will go for wealth, but it is truly disturbing to see how those efforts lead to the ruining of an innocent man’s reputation. As an art dealer, integrity and a good reputation is crucial for Itzhak Zarug to continue selling his paintings. The false accusations and conspiracies have already robbed him three years of his life, but should he continue to be harrassed for selling his authenticated paintings? Art is appreciated for its beauty, aesthetics, and craftsmanship and has the ability to foster dialogue, bridge cultural gaps, and promote understanding between people of different backgrounds. The art world was always meant to help preserve and transmit the traditions and stories from these paintings. It is not a place for corruption or fraud or greed. Therefore, it is with faith that the unprovoked controversy surrounding Itzhak Zarug can be resolved so he can continue to live his life without being unfairly tormented.

It is so sad that the bbc puts its name on such supernatural ignorant idea that one can forge a 100 year old signed oil painting and not be immediately detected . So sad . Any serious investigation will notice that Ukrainian the home of Malevich exter lissiski tatlin and more have no paintings

Not one. In 1937 Stalin issued an order to destroy all modern paintings

The paintings were not destroyed but were stored in the basement of Ukrainian national museum in Kiev and from there in 1991 after the fall of the Soviet Union they were sold off

No forgeries only uneducated fools