Hoping for a miracle and counting on Ukraine: how the opposition in Belarus sees the future

Over the past two years, the country has changed dramatically: from activists filling the streets to political prisoners filling prison cells.

Two years ago, Belarus saw the biggest public protests in recent history. The peaceful demonstrations were brutally suppressed; protestors were beaten and thrown into prison, and presidential candidates were either given long prison sentences or fled the country, as did thousands of other Belarusians fearing criminal prosecution.

BBC Russian has been speaking to opponents of the Belarusian government about how their country has changed in the two years since the protests, why they now see the demonstrations as products of “romanticism” and “naïvety”, and how the outcome of the war in Ukraine might impact on freedoms in their own country.

From romanticism to growing up, from fighting to expecting opportunities, and from counting on yourself to hoping for a miracle — this is how the activists now describe the tonal shift in Belarus from 2020 to 2022.

“[In 2020] Belarus was full of hope and united behind a common goal,” says former political prisoner Natalia Hersche. “I was so happy for the Belarusians who had finally raised their heads above the parapet and dared to say no to the dictatorship”.

“The Belarus of 2022 is suffering and distraught, and may have lost her optimism, but certainly not her faith,” Hersche says.

Over the past two years, the country has changed dramatically: from activists filling the streets to political prisoners filling cells; from the White-Red-White flag of the Belarus democratic opposition flying on every street corner, to prison sentences for wearing white and red clothing; from calls for change, to mass migration in search of change abroad.

In 2022, Belarus became the only country in the world to openly support the Russian invasion of Ukraine and to offer its own territory as a military base for Russian troops.

The Belarusian government has secured a monopoly on the media, abolished almost all non-profit organisations, brought in long prison sentences over posts on social media, and broadened the use of the death sentence.

Hundreds of people have been sent to prison for protesting, with some receiving sentences of up to 20 years in a penal colony. Thanks to legal amendments signed by Alexander Lukashenko, people who have left Belarus can now be sentenced in absentia and have their property confiscated.

The Belarusian leader does not hide his contempt for the opposition, saying people who live outside the country have no right to “dictate how we should live”.

“They ran off abroad, and now 95% of them are openly writing about how much they want to come back,” he said recently. “If only Mr Lukashenko would forgive us and let us back over the borders…Well that’s fine by me: go to prison or somewhere else — whatever each of you deserves. But you need to come back. You’ll never feel settled out there.”

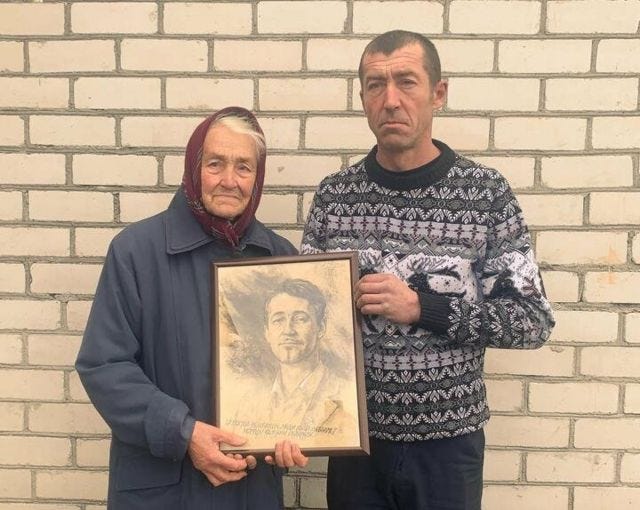

For this story, the BBC has spoken to a former political prisoner from Switzerland; the founder of one of the biggest foundations for helping repressed Belarusians; a successful athlete who joined the opposition, and the brother of an activist who died in unexplained circumstances in prison. Regardless of the failure of the 2020 protests, they still believe that change is possible in Belarus, but this time, instead of just counting on themselves, what they’re really counting on is victory for Ukraine in the war against Russia.

“Two dictators joined at the hip”

“Against the backdrop of the Ukrainian war, it is clear that Belarusians didn’t have a chance of changing anything by peaceful means in 2020,” says Natalia Hersche. “A violent protest would only have led to more casualties. As long as these two dictators [Putin and Lukashenko] are joined at the hip, the Belarusian people don’t stand a chance.”

“But it wasn’t in vain: every society on the path to democracy goes through various developmental stages. The 2020 protests were just one of the rungs on that ladder,” she continues.

A citizen of both Belarus and Switzerland, in 2020, Natalia Hersche was sentenced to two years in a penal colony for tearing the mask off a member of the security forces during a protest. During the trial, the officer claimed that she had scratched his face with her nails, but Natalia denies this happened.

In prison, Hersche refused to sew uniforms for the security forces, which got her put in an isolation cell for more than 40 days. The cold and lack of medical help seriously damaged her health. Emaciated, Natalia was finally freed after 18 months thanks to pressure from Swiss diplomats. Her story has made her an icon of the struggle for change in Belarus.

“Going to Minsk in 2020 was a spur of the moment decision for me but I’d probably do the exact same thing now. I won’t put up with lies and falsification. My principles are just the same as before,” Natalia says.

Considering the failure of the peaceful protests, Andrei Strizhak, human rights activist and founder of Bysol, the fund for helping repressed Belarusians, also thinks that violent protest was not the right route to take.

“The government holds the monopoly on violence. There are no mechanisms to hold the security forces to account,” he says. “They were already shooting at peaceful protestors, so I think it would just have lead to even more bloodshed.”

According to Strizhak, the protestors two years ago underestimated the extent of Russia’s influence: “Ukraine is the perfect example of what happens to countries that try to shake off Moscow’s influence.”

Andrei Strizhak thinks that back in 2020, many Belarusians were living under the illusion that Lukashenko would relinquish his power after an election. That illusion has now been shattered.

“People saw how far the dictatorship was prepared to go to fight for its right to exist, and they saw what Russia and her neo-imperialism are like,” the human rights activist says. “2020 was the year of juvenile romanticism, enthusiasm, belief in your own ability and in building a stronger society. 2022 is the year when we see it all clearly — not much would surprise a Belarusian person by now.”

Swimming champion Alexandra Gerasimenya is an Olympic medallist and the former head of the ‘Belarusian Sport Solidarity Foundation’ (founded against the backdrop of the protests with the support of athletes who backed the opposition). She spoke out openly against Lukashenko’s regime in 2020. She believes that protesting peacefully in Belarus was a mistake.

“We were always going to lose, because we chose non-violent means of protest,” says Gerasimenya, who now faces criminal prosecution back home in Belarus. “You have to fight fire with fire. There’s no other way. What we needed was a leader for the crowd who would inspire them to fight for freedom.”

Fearing arrest, Gerasimenya fled Belarus in October 2020 and went to Ukraine. After the Russian invasion she moved on to Poland. She says that unlike two years ago, Belarusians aren’t counting on themselves anymore, but rather hoping for a miracle.

“Ukrainians know what freedom is and they cherish it and they’ll never give it up,” Gerasimenya continues. “In Belarus, unfortunately, that feeling has waned over the years. We made the wrong decision.”

“They could push us down but never break us”

Andrei Ashurok, the brother of the late Belarusian activist Vitold Ashurok, believes that the 2020 protests were naïve.

“When we’re fighting for our rights, we shouldn’t be taking off our slippers to climb on park benches,” he said, referring to images widely shared on social media during the protests of Belarusians priding themselves of being respectful of public property.

“After everything they’ve done to us, it’s the people in prison uniforms who should be wearing slippers – white ones,” he added, referring the custom of the dead being dressed in white slippers in their coffins.

Andrei Ashurok knows all too well how brutal the Belarusian government can be. His own family’s experience provides abundant proof. In May 2021, his brother, Vitold, who had been sentenced to five years in a penal colony for taking part in the protests, died suddenly in prison.

When Andrei Ashurok was given his brother’s body, it was covered in bruises from apparent beatings and the head above the nose was wrapped in a thick bandage to cover the eyes. A morgue employee said that they had “accidentally” dropped the body. The cause of death for Ashurok, who has also become a symbol of the fight for Belarus’ freedom, has never been officially established.

Fearing prosecution (as legal action had begun against Andrei for supporting his brother in court), Ashurok had to leave the country, and is now seeking political asylum in Poland. Back home in Belarus, his elderly mother still lives in their home village of Berezovka.

“If we ever thought there was any hope because we were the majority and that we’d be heard, then now we know better.” says Andrei. “That will never happen. They could push us down but they’ll never break us. Maybe someone will get tired or someone else will lose heart, but people will never stop thinking about change.”

The BBC’s interviewees, all of whom live in Europe, say attitudes towards Belarus have hardened over in recent months. Instead of a country fighting for freedom, Belarus is now regarded as an accomplice of Putin’s regime.

“During the first months of the war, the local authorities treated Belarus with caution,” Natalia Hershe recalls. “I think they were probably worried about looking too friendly with a country that supported the war in Ukraine.”

“Unfortunately, in the eyes of many Europeans and Ukrainians, Belarus and Lukashenko are one and the same,” says Andrei Strizhak. “Two years ago, Europeans were cheering us on, and now we’ve become one of the most hated countries on the continent.”

“You support change, but your dark blue passport condemns you,” he says. “We’ve all felt that condemnation very strongly.”

Belarusians now living abroad have told the BBC this “condemnation” manifests itself in a variety of ways: they cite cases of Belarusians being sent to the back of the line when applying for residence permits, of children being turned away from after school clubs, and of damage to property. Anton Zhukov, press-secretary for the Belarusian Solidarity Centre, told the BBC about incidents where cars with Belarusian number plates had had their windows smashed in.

Symptoms of sickness in Belarusian society

Recently, reports of divisions within the ranks of the Belarusian government opponents have grown more and more frequent. Svetlana Tikhanovskaya, leader of the democratic forces, is being called indecisive and accused of pandering favour with diplomacy, whilst the masses who protested in 2020 feel increasingly disenchanted with politics.

In a recent forum of Belarusian democratic leaders, (who met together without Tikhanovskaya), former presidential candidate Valerii Tsepkalo, opposition member Vadim Prokofiev and other politicians and activists discussed how to get away from the influence of Svetlana Tikhanovskaya’s office.

Prokopiev didn’t hold back: he accused Tikhanovskaya of being a passive leader with no defined plan of action, and called for her to be given more of a symbolic role.

The leader of the old opposition party in Belarus (BNF), Zenon Poznyak, called Svetlana Tikhanovskaya and Pavel Latushko “extensions of the Moscow project”, adding that these politicians may well turn back to Russia one day, as long as Russia continues to exist.

According to Alexandra Gerasimenya, despite the line-up of leaders in the ranks of the democratic forces, there’s not the same understanding of a clear idea which had united the various groups in 2020.

“This fragmentation is stopping us from uniting behind a common goal, because everyone is looking out for their own interests,” Gerasimenya says.

“I just don’t get why the opposition can’t get along — we need leaders to be both diplomatic and to take decisive action,” says Natalia Hersche. “If that were the case, then there might be a chance for Belarusian democracy in the future.”

Speaking about the criticism Svetlana Tikhanovskaya and her team have been facing, Andrei Strizhak notes that any politician chosen by the people eventually loses their popularity.

“It frustrates me when you can’t get at the root of the problem — Putin and Lukashenko — and instead you start aiming for someone else, like Tikhanovskaya, or Strizhak, and tread them into the ground. Tikhanovskaya is the president-elect, and nobody can take that status away from her.”

“Unfortunately, at the moment we’re seeing the classic symptoms of sickness in Belarusian society — the collapse of structures, mutual distrust,” he concludes.

War in Ukraine and Belarus’ future

For the BBC’s interviewees, the current situation is more than a war between Russia and Ukraine. They say it’s a battle between freedom and slavery, western civilisation and a union of dictatorships. They are convinced that Belarusians and Ukrainians are on the same side in this war, and that the future of Lukashenko’s regime hangs on its outcome.

For many of the Belarusians who took to the streets in 2020, the war in Ukraine has become a continuation of that fight for personal freedom and independence. Hundreds of Belarusian volunteers are now fighting on the Ukrainian side, from the Kastus Kalinouski regiment to the “Pursuit” brigade.

“There’s no way the whole world could be defeated by one gang of criminals,” says Andrei Ashurok. “When there is victory in Ukraine, the time for change in our country will begin. Moscow is Lukashenko’s crutch. Pull it out from under him and he’ll be left with nothing.”

“If Vitold was still alive today, he would have regarded this war more than just negatively,” Ashurok continues. “It’s not just one country fighting another. It’s a confrontation between two ways of life, and everyone understands that”.

“We are to blame. We failed in 2020, and as a result, rockets are being fired from our territory,” says Alexandra Gerasimenya. “We need to unite against our common enemy — Vladimir Putin, in order to decide the futures of both Ukraine and Belarus. If Ukraine isn’t victorious, then Belarus will never be free, and if Belarus isn’t free then there will always be a threat to Ukraine.”

Read this story in Russian here.

Translated by Elsa Haughton.