Azerbaijan’s ethnic minorities: troubled co-existence

Armenians' mass exodus from Nagorno-Karabakh put the spotlight on Azerbaijan’s decidedly mixed record of protecting the rights of some of its many other minority communities.

By Magerram Zeynalov.

As Azerbaijan moved to reassert control over Nagorno Karabakh in September, the local Armenian population were assured their language and culture would be protected. In the event few Karabakh Armenians decided to risk testing that promise. Their mass exodus underlined not just the deep mistrust between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, but also put the spotlight on Azerbaijan’s decidedly mixed record of protecting the rights of some of its many other minority communities.

"I was 12 or 13 years old when I found out that I was a Tat," says Alovsat, a schoolteacher (name changed at the request of the individual). His family moved from Moscow to the suburbs of Baku in the early 1990s, and throughout his childhood, Alovsat considered himself an Azerbaijani.

Tats are an ethnic minority of Persian origin, mainly residing in the vicinity of the Azerbaijani capital. There are fewer than 28,000 of them in the country, which is approximately a quarter of one percent of the total population. The only thing that distinguishes them from Azerbaijanis is their language, which belongs to the Iranian group, but today it is considered to be endangered.

"My father was fluent in Tat, and so was the older generation, but no one taught us Tat anymore. There was no literature, no self-instructional materials, and I didn't know the language," says Alovsat. In his adult years, he became interested in his native culture and found an Azerbaijani Tat group on Russian social media platform "VKontakte." In the group, they shared songs in Tat or original texts about the language, but there were no books or textbooks available to help beginners.

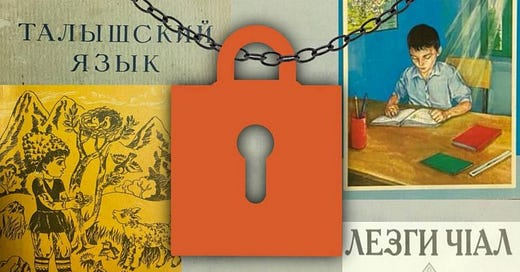

The largest ethnic minorities in Azerbaijan, such as the Lezgins (official census data from 2019 states 1.7% of the population) and the Talysh (0.8%), face a similar problem. Pensioner Adalat from the southern town of Masalli remembers how, due to the lack of textbooks, Talysh language lessons in schools were replaced with physical education and music. This year, textbooks have appeared, and three of Adalat's grandchildren have started learning their native language at school. However, the number of lessons has been reduced from four per week to two. According to the pensioner, children only know Talysh because they speak it at home.

BBC is blocked in Russia. We’ve attached the story in Russian as a pdf file for readers there.

The Talysh language, spoken primarily in the southeast of Azerbaijan, is also similar to Persian, while the religious beliefs and customs of the Talysh people, like those of the Tats, are similar to Azerbaijani. As for the Lezgins, they are a Dagestani people living in the north, near the border with Russia. Besides language, another distinguishing feature between them and Azerbaijanis is their Islamic sect; the Lezgins are Sunni Muslims.

They, too, lack teaching materials. Sabina (name changed), a schoolteacher in the Gusar district, explains, "In a class of 30 students, only about ten have textbooks, and those are old and worn, mostly passed down from their parents." These Lezgin language textbooks were brought from Russia’s Dagestan region at different times. Sabina mentions that the Ministry of Education promised to provide new textbooks, but they have not received them yet.

According to her, teachers do their best to cope with the situation: "They provide materials themselves, create texts for dictations, find stories online so that the children can become literate." Despite Lezgin being the primary language of communication in their village, it is taught only once a week from the first to the ninth grade.

What does the law say, and what happens in practice

The right to access information and education in one's native language, including the availability of teaching materials and language schools, is enshrined in the commitments that Azerbaijan undertook when it signed several international documents over 20 years ago aimed at protecting the rights of minorities related to language and culture. These documents include the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages and the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities.

However, in practice, the Talysh and Lezgin communities do not have access to proper language education, developed media outlets, or schools. Places like Gusar, where the Lezgins live, Lankaran, a Talysh city, or the suburban areas of Baku populated by Tats, do not visibly differ from other cities and villages. Signage and outdoor advertising in these areas are only in Azerbaijani.

Historian Arif Yunus and human rights advocate Eldar Zeynalov share the view that Azerbaijan signed the necessary documents not out of sincere intentions to support minorities but to meet the requirements for joining the Council of Europe.

Zeynalov notes that minority rights are scattered across different laws, including the Criminal Code and the Constitution, but they have not yet been consolidated into a single law on ethnic minorities.

On the other hand, deputy and member of the parliamentary commission on international relations, Rasim Musabekov, believes that a separate law is not necessary precisely because all the provisions are documented in international agreements that Azerbaijan has signed.

He acknowledges that not everything is necessarily adhered to in practice but mentions that there have been no complaints related to the implementation of these charters in Azerbaijan.

The issue extends beyond the absence of school textbooks. Gilal Mamedov, a member of the Public Council of the Talysh people, points out, "There are still no methodological books for teachers themselves, and they are not producing new personnel for teaching the Talysh language." He mentions that Azerbaijani universities lack a department for studying the culture, traditions, and languages of the peoples of Azerbaijan, despite their existence during the Soviet era.

"I wonder which textbooks Armenians will use in schools now. Their heroes are our enemies, and their narrative about Karabakh contradicts ours."

Historian Arif Yunus, in his book "Azerbaijan at the Beginning of the 21st Century: Conflicts and Potential Threats," writes that in the early Soviet era, the state supported the development of minority languages, sponsoring the translation of popular literature into languages like Talysh. However, today, authors of both artistic and scientific works about local folklore publish them at their own expense.

The Ministry of Education, in response to a request from the BBC, stated that new textbooks for Talysh, Tsakhur (spoken by around 13,000 people in Azerbaijan, or 0.13% of the population), and Khinalug (Khinalug people being one of the smallest ethnic groups in Azerbaijan, with almost all 3,500 individuals living in a single village in the northeast of the country) languages were released this year. They added that work on updating or preparing textbooks for languages of other minorities continues.

Separatists or patriots?

One of the reasons why Azerbaijani authorities often view national minorities with suspicion is their sensitive approach to the issue of separatism.

In 1992, when Baku refused to join the newly formed Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), which emerged in the aftermath of the Soviet Union's collapse, and demanded the withdrawal of Russian troops from the country, historian Arif Yunus writes that an organization called Sadval became active in the north of Azerbaijan, where the Lezgins reside. Sadval aimed to unite the territories inhabited by Lezgins in Russia and Azerbaijan into a single state. Their headquarters were located on the other side of the border, in Dagestan, and Yunus associates their activity with Moscow's attempt to exert pressure on Baku.

However, Sadval has long since abandoned the idea of creating "Lezgistan," and there have been no reports of separatism in Azerbaijan related to them for many years.

The situation with the Talysh people is somewhat different. In 1993, during the first Karabakh war, a self-proclaimed autonomy called the Talysh-Mugan Republic was established in the south. However, as noted by Arif Yunus, this was hardly an example of ethnic separatism.

The creators of the autonomy were military personnel who had been fighting in Karabakh as part of the Azerbaijani army, including both Talysh and Azerbaijanis. The self-proclaimed president of the autonomy, Alikram Gumbatov, identified as an Azerbaijani and served as the Deputy Minister of Defence in independent Azerbaijan. The autonomy lasted only two months, and Gumbatov eventually ended up in prison.

In the small coastal town of Lankaran, predominantly inhabited by Talysh people, one can find advertisements on fences inviting people to join the army on a contract basis. Several years ago, even before the fall of 2020, a sign was spotted on the door of a restaurant that read "Free lunch for the families of those who died in the war" — referring to the first war of 1992-1994. A local resident explained that "true patriots" live there and expressed frustration that many view Talysh people as separatists.

Two years ago, the Public Council of the Talysh people expressed outrage when, at a music festival dedicated to the victory in the second Karabakh war, Talysh songs were sung in Azerbaijani. The Council saw this as part of "various cunning plans aimed at the assimilation and discrimination of the Talysh people" and demanded that the authorities "stop such manoeuvres." This demand was preceded by a lengthy preamble highlighting how the Talysh people supported the country in its victory over Armenia.

A painful subject

The head of the Public Council of the Talysh people, Gilal Mamedov, was one of the editors of the only Talysh-language newspaper in Azerbaijan, "Tolishi Sado" ("Voice of the Talysh"), until 2011. In 2012, he was arrested on charges of treason and incitement to ethnic hatred. International human rights organizations considered him a political prisoner. He was granted clemency by the president four years later.

The previous chief editor of the newspaper, linguist Novruzali Mamedov, was also arrested on charges of treason in 2007. Human rights advocates claimed that he was beaten during his arrest, and in prison, he was subjected to torture, which left him unable to move. Demands from international human rights organizations to release him and a personal letter from Mamedov's wife to the president were ignored, and in 2009, Novruzali Mamedov died in prison.

Fahradin Aboszoda, another prominent Talysh figure who was a politician and a book editor, fled to Russia to escape charges of treason. Human rights activists had requested Moscow not to extradite him, citing that deportation would put his life at risk. In 2020, he was extradited to Azerbaijan, where he died in prison, officially reported as a suicide.

During Aboszoda's arrest, only foreign human rights activists spoke out in his defense, while local activists remained silent and did not include him in any lists of political prisoners. Historian Arif Yunus explains that even human rights activists in Azerbaijan often consider so-called "national interests." He says, "People, opposition, and human rights activists are very afraid to go against public opinion."

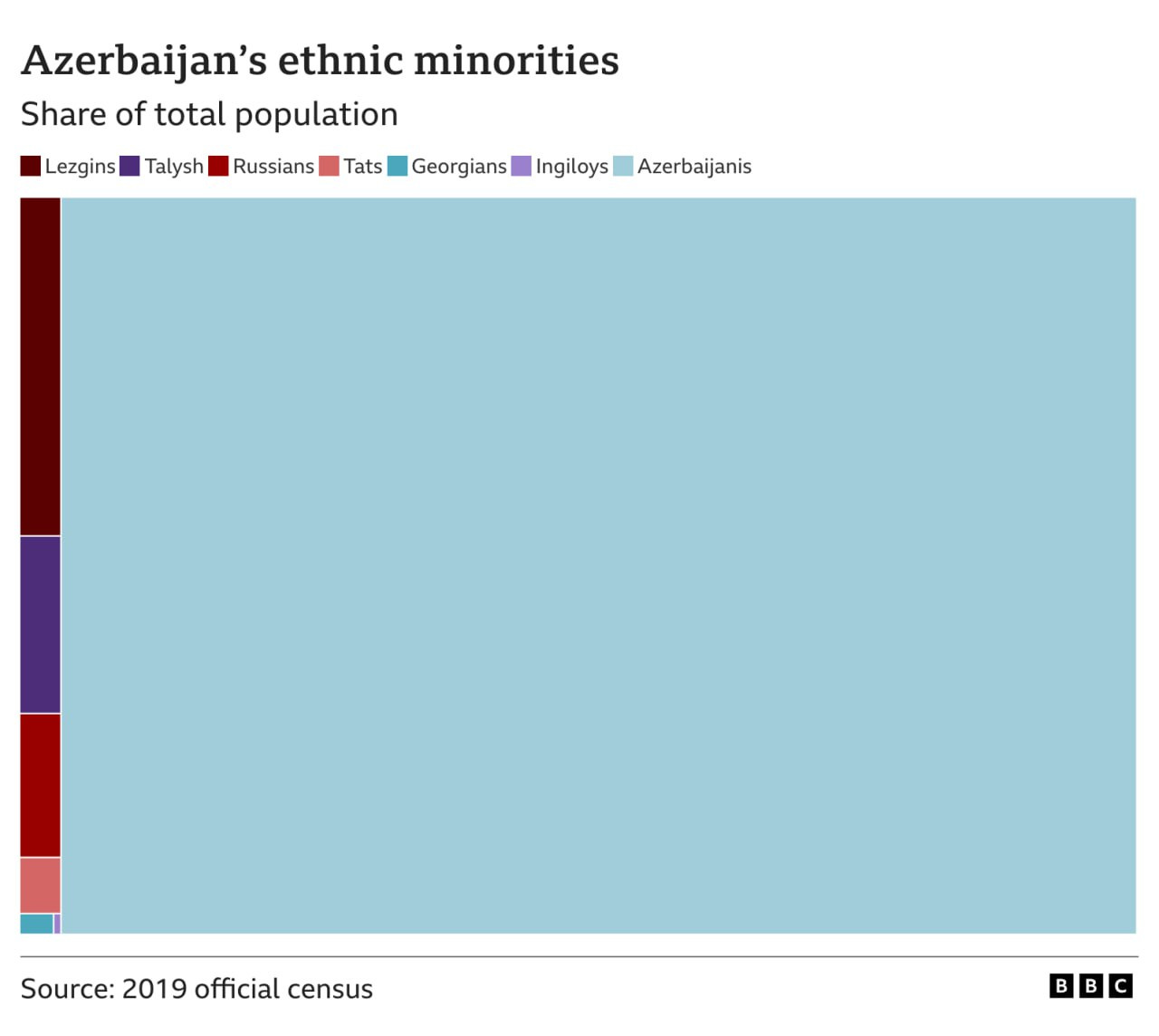

The issue of separatism is extremely sensitive not only for the Azerbaijani government but also for society, as noted by sociologist Bahruz Samedov. He explains that it is connected to the discourse that emerged after the return of Heydar Aliyev (the father of the current president) to power in 1993, which emphasized his role in saving the country from disintegration, suppressing a rebellion in Baku, ending the existence of the Talysh-Mugan autonomy, and strengthening the power of central government.

An example of this is the history of Heydar Aliyev's native Nakhichevan — an exclave separated from Azerbaijan by Armenian territory. For almost a century, the region had autonomous status and operated under its own laws, until last year when President Ilham Aliyev, amid high-profile arrests of Nakhichevan officials, removed (officially citing health reasons) Vasif Talibov, who had led the region for 27 years, and appointed a newcomer from Baku, effectively ending Nakhichevan’s autonomy.

In the context of the established absolutism, Samedov says that any form of political identity, not just ethnic, is seen as a threat to the state. Without political representation experience, many in Baku view even demands related to cultural identity, such as the right to information, books, and songs in one's own language, as separatism.

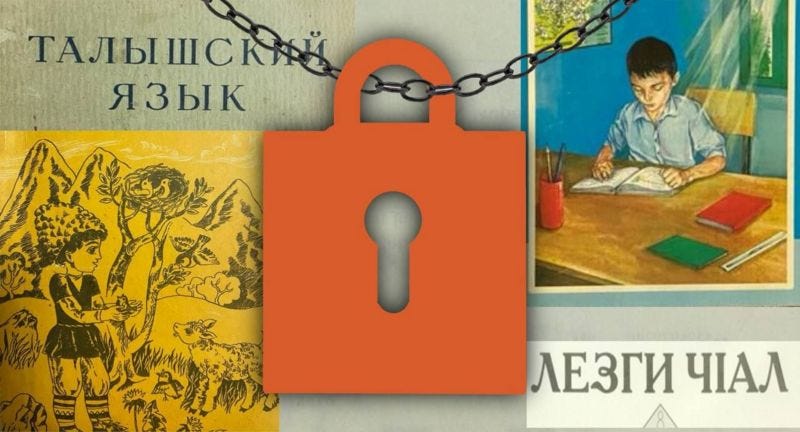

According to official data, ethnic minorities make up about 5% of Azerbaijan's population. However, some Azerbaijani experts, including Arif Yunus and Eldar Zeynalov, believe that the 2019 census was conducted dishonestly, and there are doubts about the official estimates of both the minority populations and the total population.

Some minorities, such as the Russians and Georgians, have more opportunities to study in their own language and develop their culture compared to others.

Russians are the third-largest ethnic minority in Azerbaijan after the Lezgins and Talysh people, with around 71,000 individuals, or 0.7% of the population. Georgians are significantly smaller in number, with 8,400 Georgians and 1,800 Ingiloys (a group of ethnic Georgians who identify differently and speak the Ingiloy dialect of the Georgian language).

Both Russians and Georgians have schools in their own language, and educational materials are supplied by Russia and Georgia. Nearly every school in Baku offers instruction in Russian, and there are Russian-language universities, a branch of Moscow State University, and several cultural centres in the capital.

Sociologist Bahruz Samedov explains the differences in approach by the presence of "patron states" for Georgians and Russians with whom Baku has good relations. He says, "This eliminates the risk of politicization based on ethnicity."

What about the Armenians?

In explaining why Azerbaijan does not fulfill its obligations regarding the protection of national minorities, researchers point out that the Azerbaijani nation is still in the process of formation, and Azerbaijani nationalism only began to emerge in the early 20th century, later than in Europe and the Caucasus.

In his essay, researcher Kanan Gaibov notes that in its attempts to unify society, the authoritarian regime is moving toward mono-ethnicity, primarily through the prioritization of the Azerbaijani language. Additionally, the shadow of the Karabakh conflict has loomed over Azerbaijan for the entire 30 years of its independence.

As a result of Azerbaijan's military operation in September, 2023, the entire Nagorno-Karabakh region, once populated by Armenians, came under Baku's control. According to the United Nations, out of tens of thousands of Karabakh Armenians, there are now no more than a thousand left in the region.

For the remaining population, the Azerbaijani authorities opened a website for initial registration and obtaining Azerbaijani passports. President Aliyev expressed confidence that Armenians would be able to successfully integrate.

The Azerbaijani authorities offered subsidies to farmers, tax and customs incentives, social payments, the organization of local governance through municipal elections, as well as protection for language, faith, and culture to the Armenians of Karabakh.

However, both experts and Armenians who fled the region do not believe in these promises. Many express concerns about potential violence and discrimination, and they remain sceptical about the ability to coexist peacefully in the region.

“If an Azerbaijani kills me on the street, the court will say it was my fault. If I leave one of them with a black eye, I will go to prison for 20 years,” said an Armenian refugee to the Russian website ‘Ekho Kavkaza’.

Elections at all levels in Azerbaijan are conducted with violations. Activists, politicians, journalists, and even farmers in remote regions face police violence, and Armenian churches are declared Albanian (there was once a Christian state, Caucasian Albania, in this region in the Middle Ages).

Moreover, it is unclear whether Azerbaijani society is ready for the new reality. Hate speech against Armenians, including in textbooks, is still widespread in schools. As historian Arif Yunus notes, "I wonder which textbooks Armenians will use in schools now. Their heroes are our enemies, and their narrative about Karabakh contradicts ours."

However, sociologist Sergey Rumyantsev suggests that after the mass exodus of Armenians from Karabakh, the question of their rights may have lost its significance. He asks, "Will it be necessary to provide rights to a non-existent ethnic group?"

If Armenians do return, Baku may, from an international image perspective, create conditions for them to study in their native language, speculates Rumyantsev. However, he believes that this would mean living in complete isolation, where the region may be visited by journalists or politicians, and residents would have to express loyalty to the president. He refers to such a situation as a "ghetto with all the Euro conditions." He questions whether such conditions can be considered as the protection of the rights of an ethnic group.

A report from the International Committee of the Red Cross, whose employees visited Karabakh, indicates that Stepanakert (known as Khankendi to Azerbaijanis) is mostly populated by elderly people and those who could not leave. According to a UN report, it is currently difficult to determine whether the local population intends to return.

Read this story in Russian here.

Azerbaijan’s Karabakh challenge: a genuine commitment to change, or more empty words?

By Famil Ismailov. Almost all the Armenians living in Nagorno-Karabakh have now left the disputed enclave since Azerbaijan retook control in a lightning military operation on 19 September. After three decades of bloodshed, mutual mistrust and hostility people unsurp…