“Armed Russian Governor spotted in the Donbas.” Why bureaucrats have been hurrying to the frontline

A growing number of Russian officials are openly making trips to occupied areas of Ukraine, even though visiting frontline areas is dangerous.

By Petr Kozlov

A growing number of Russian officials are openly making trips to occupied areas of Ukraine, even though the situation there isn’t straightforward for Russia, and visiting frontline areas is dangerous. To begin with, you could count such trips on one hand. Now they are becoming a trend.

In fact, even those who previously criticised the enthusiasm of their colleagues and comrades are now themselves keen to be seen making similar journeys.

BBC Russian takes a look at what compels Russian officials to spend time in Ukraine’s captured regions.

Armed and looking tough. How Governor Kozhemyako turned up in the conflict zone

The capital of Russia’s Primorsk territory, Vladivostok, is separated from the Donbas by 7,000 kilometres as the crow flies. So waking up one morning in late April, residents might have struggled to imagine that their governor had gone missing.

But even his closest underlings were in the dark about Oleg Kozhemyako’s whereabouts.

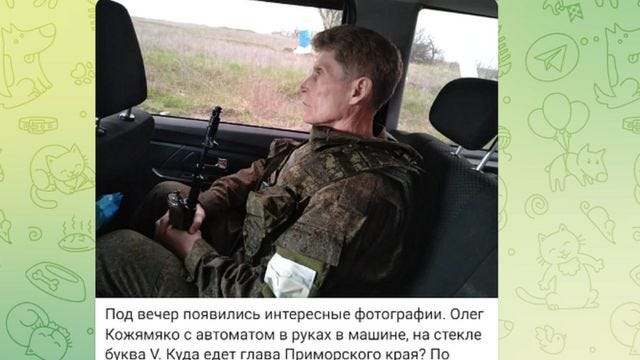

Towards evening, news arrived from an unexpected source, apparently from Russian-occupied Ukrainian territory. Photos of the governor of Primorsk, dressed in camouflage and body armour, and armed with an automatic weapon, began to circulate on the social networking platform Telegram.

Judging by the photo and his tough expression, Kozhemyako was somewhere in the conflict zone, seated in the back of a moving car with the ‘V’ symbol taped to it. It was clear that he was travelling over rough terrain, and there were buildings with the Ukrainian flag visible through the window.

Local media splashed headlines: “Oleg Kozhemyako spotted armed and in uniform in the special military operation zone in the Donbas”.

A local administration official, called up by journalists, was clearly taken by surprise. So he improvised, admitting he had only heard of his boss’s trip via the internet, but then declaring with confidence that Kozhemyako must have left for the conflict zone to support soldiers from Primorsk who were “fighting against the Nazis”.

“Considering his personal relationship with our marines, he may well have gone to meet them as a show of support,” the official told ‘Vostok-Media’. “These are our guys, after all, fighting against the Nazis right now, risking their lives. This matters to him, knowing his especially respectful attitude towards people in uniform”.

“Say the letter ‘Z’ loud and clear. Or get out”

Since the beginning of the war, no public orders or appeals to civilian officials, politicians, or cultural figures to visit the sites of recent battles have issued from the Kremlin.

However, like Kozhemyako, the first governors have carefully risked venturing to the zone of the military operation.

During more than five months of war, dozens of senior Russian officials have travelled to the occupied territories. And if the first of them, the deputy head of the presidential administration, Sergey Kiriyenko, arrived with an official mission – to decide on the possibility of organising referendums on the Russian annexation of Ukrainian territories; and if the deputy prime-minister Marat Khusnullin examined the main matters of his official brief, construction and reconstruction - the point of the governors’ visits has been less obvious.

Still, the leaders of Russia’s federal districts have become mass “tourists” in the war-torn parts of Ukraine.

It is possible they’ve understood something: that with time the Kremlin’s position may get tougher. If at the very beginning of the war nobody required anything from them, and individual governors acted intuitively, now things are verging towards a duty.

Perhaps it is no coincidence that Andrey Klishas, vice-chairman of the Russian Federation Council, reposted on his Telegram account the philosophy of the Russian thinker and Eurasianist Alexander Dugin. Western media have sometimes referred to him someone Vladimir Putin listens to as one of the main ideologists of modern Russia.

In the post, Dugin called on Russian elites to decide openly either to support the war publicly - or to step aside.

“I think that all senior Russian officials should openly express their attitude towards the special military operation or leave office. Some people are suspiciously silent. Regardless, we are beginning to interpret their silence as we see fit. Do not lead us into temptation, but say just that one letter ‘Z’ clearly and loudly. Either that, or honourably get out of our sight”, wrote Dugin. [The letter ‘Z’ was daubed on many Russian vehicles at the start of the invasion and has become a symbol of support for the war.]

Meanwhile, Senator Klishas suggests going further still – to demand that big businesses, politicians, and public figures make their stance clear: “People have the right to know the position of all leaders of politics, business, and society on this key question.”

“I am one of us, and I am a supporter!”

But even if we put aside the supposed (or increasing) “Kremlin obligation”, there is a whole host of reasons why officials visit the occupied territories.

At the very beginning of the war, when the most tough-skinned representatives of the political establishment began to come to their senses, they realised that the world, Russia, and the rules of the game within the Russian regime had all changed dramatically. This is the picture painted to the BBC, on condition of anonymity, by a Russian federal official, a regional governor, and an individual close to the leadership of the federal government.

One of the reasons why some public politicians quickly started supporting the war and went to the occupied Donbas was a desire to improve their position and reputation in the eyes of the federal centre.

As an example, a source close to the presidential administration referred to the case of Radiy Khabirov, head of the republic of Bashkortostan. According to the source, Khabirov’s position and future in the republic had been called into question by the Kremlin.

An experienced apparatchik, Khabirov felt vulnerable and decided to take the initiative: “to choose patriotism and show that I am ‘one of us’, and a supporter”.

As a result, he was the first governor to visit the Donbas – less than a month after the beginning of the invasion. He quickly reported the trip on his Telegram channel, and later became one of the first to set up a volunteer battalion from his region.

Thanks to his quick response, Khabirov was able to improve his standing and boost his political capital in the eyes of the presidential administration, in turn increasing his prospects of remaining in office, the source said.

“It was clear that the Kremlin did not punish Khabirov for the trip, and even praised him for it. This served as the signal for further mass visits”, the Russian political scientist Konstantin Kalachev told the BBC.

According to the independent “Meduza” news site, the war and the trip to the frontline could have saved from likely dismissal another regional chief, Governor Alexander Beglov of Saint Petersburg.

Other regional leaders followed Khabirov to Donetsk and Luhansk. Soon, visits by governors became a frequent event, and a whole “patronage” tour to cities of the Donbas was invented.

Such trips have become as identical as two drops of water: the arrival, followed by a meeting with the head of the self-declared “republic” or of the town administration; the signing of cooperation agreements; and the taking of a few photos for the governor’s Telegram and other social media feeds.

Faced with the need to travel to the Donetsk or Luhansk People’s Republics, regional leaders take different approaches. Some stress patriotism, geopolitics, and the rebuilding of infrastructure. Others in public focus on the mutual benefits of possible economic cooperation.

Another group prefers to avoid drawing attention to themselves, according to Russian political analyst Mikhail Vinogradov. For example, Moscow mayor Sergey Sobyanin’s trip was much less widely promoted than that of his counterpart from Saint Petersburg.

Similar visits have been made by the regional heads of Altai, Samara, Rostov, Volgograd, and Voronezh, as well as dozens of other members of federal government. Almost all reported that they had brought humanitarian aid, medicine, hardware and construction supplies.

At the same time, the economic situation in many of these regions has worsened in recent years. A cursory glance at local media outlets shows stories about unresolved problems in the medical and construction sectors, as well as to do with the provision of medicine, utilities, and civil amenities, among many others.

However, not all such trips turn out to be a public relations triumph in the governors’ own regions.

For example, Sergey Menyaylo, head of the republic of North Ossetia-Alania and a former career military officer, was fired upon by “Ukrainian saboteurs” during his visit, and reportedly suffered concussion.

While Menyaylo denied this, he did admit to having visited the Donbas. And hastily returned to Russia.

The Volodin incident

Visiting the occupied zone, while fraught with risks, does not automatically grant a pardon, nor is it protection from possible dismissal or other future career hazards. But after the war, however it ends, bureaucratic logic dictates that there will be “winners who served” - and they will bid for power.

To enter this cohort, you need to acquire leverage by participating in the war in this fashion, a source close to the leadership of the Russian government told the BBC.

“The Volodin case is an example. They are starting to put the pressure on. Suddenly you realise that what yesterday seemed to be a mistake, is today the only possible option”, he stressed.

Frequent visits by Duma deputies to captured Ukrainian lands turned into a public furore involving the speaker Vyacheslav Volodin. During one parliamentary session, Volodin reprimanded MPs for their frequent absences, and demanded an end to the “excessive fervour of certain deputies for engaging in matters that are not their business”.

He was answered by his long-time public opponent, the secretary of the General Council of the “United Russia” party and vice-speaker of the Federation Council, Andrey Turchak, who himself constantly pays visits to the Donbas. He claimed that his work would continue, and advised against paying attention to “officials who are out of touch with reality, who’ve worn out their trousers in comfy armchairs”.

This dispute was resolved, as usual, by Vladimir Putin, who praised MPs who “ventured into the war zone”. Just a week later, Volodin’s press service abruptly announced that he too had arrived in Luhansk.

In a speech to the parliament of the self-proclaimed Luhansk People’s Republic, Volodin assured them that Duma deputies “had been waiting for this meeting for 30 years”.

“Among governors and other officials, there are, as always, those who are very enthusiastic, as well as those who are sceptical. But what fool would show it?”, asks Kalachev rhetorically. “Each simply wants to get through all this. To fit in. To increase his market value. Maybe even to rise to a higher level”.

The unity of fear?

Losing the war would result not only in a “non-threatening Russia, but also a pathetic one”, said a regional governor talking with the BBC. And the international community is no longer willing to give Russian elites the room to manoeuvre.

This provides yet another reason for encouraging officials, governors, and politicians to “rally behind the great leader”. Thereafter, he continued, there is only one direction left: further militarisation, including of mindset, and the hatred of Europe.

“Regardless of one’s attitude to the war, everyone understands that whatever happens, nothing good can be expected to be on offer to those who worked in government unfavourably”, the regional governor added. Fearing for their safety, they agreed to speak to the BBC only on condition of anonymity.

“If it has come to the destruction of monuments to Pushkin [in Ukraine], then everyone [Russian politicians and officials, in the event the invasion of Ukraine ends badly] is f*****. That is why everyone is pulling together and demonstrating unity”, he believes.

Read this story in Russian here.