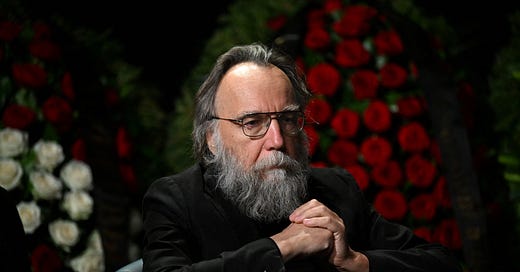

Fascism and Trolling: How much are the ideas of Alexander Dugin shared by the Kremlin?

A post-modern project made up out of occultism, conspiracy theories, esoterica, neo-fascism, Soviet sub-culture, and the ideas of the new political right? Let’s have a look.

By Grigor Atanesian

In reporting the news of the death of Darya Dugina, western media refer to her father as the ‘brain’ of the Kremlin, and his ideology as the doctrine of the Russian authorities. Yet, Dugin himself never has had a unified political doctrine. His teachings are a post-modern project made up out of occultism, conspiracy theories, esoterica, neo-fascism, Soviet sub-culture, and the ideas of the new political right and the new left.

Alexander Dugin has hopped from imperialism to masonic conspiracies, the songs of Russian pop star Tatiana Bulanova, and the philosophy of Martin Heidegger. Perhaps the only concrete position he has maintained over the years has been his hostility to an independent Ukraine, and his conviction that it presents a mortal threat to Russia.

We take a closer look at Dugin’s ideas, and in what way they mesh with the ideology of the Kremlin.

Falsifying ‘Eurasianism’

“You poured the dark wine

On the otherworldly forests

As SA divisions marched

Towards your sickened East”

Such were the breathy words to strummed guitar in a song named ‘Tango SA’, recorded on tape in 1986 by one Hans Sievers. The SA here refers to the Sturmabteilung: the Nazi assault troops. Sievers – that’s the pseudonym at the time of 24-year-old Alexander Dugin, the son of the marriage of a doctor and a general in the Soviet military intelligence.

The esoteric Nazi aesthetic, mixing racial theories with mysticism, came from the circle of writer Yuri Mamleyev, whose members studied such things.

“Dugin’s intellectual history starts with the Mamleyev circle,” says Igor Torbakov, senior research fellow at Uppsala University in Sweden. “It was a counter-culture of kitchen conversations.” [In Soviet times, controversial subjects were often discussed in the kitchen with taps running in case the home had been bugged.]

The circle indulged in the mystical traditionalism of French writer René Guénon and the neo-fascist Italian baron, Julius Evola. In particular, it was Guénon that Dugin cited most frequently in his early writings. After that, he set off in pursuit of the primitive, sacred traditions of humanity that western civilisation had allegedly lost thanks to its cult of science and reason.

Yet Dugin’s interest in fascism wasn’t limited to esoterica. In 1988, he joined the ‘Pamyat’ – ‘Memory’ – society of militant nationalists and anti-semites.

In the early 90s, Dugin began to call himself a ‘Eurasianist’, in the manner of the political and theological theories of émigré Russians who saw the country’s post-communist future in a pivot to the east, and the renunciation of democracy and market economics.

The Eurasianists believed Russia had orientated itself towards Europe, competing and comparing herself to it, for more than 300 years. Yet the country, they said, had eastern roots – the principality of Moscow was the inheritor of the Mongol-Tatar state, not that of Kyivan Rus.

Dugin has now “jumped on the bandwagon of Eurasianism, and being a talented intellectual entrepreneur, managed to project himself as the chief Eurasianist of them all,” says Igor Torbakov, who has made a study of the classical phase of the movement of the 1920s and 30s. He thinks Dugin saw parallels in the situation following the collapse of the USSR with that described by the Eurasianists. The imperialists of the 1990s stood before the same question as their 1920s forebears: how to rethink empire.

“Eurasianism was nothing more than an unsuccessful attempt to give a scientific basis to the idea of unifying the peoples of Russia and Eurasia and scientifically justify maintaining the entirety of the Russia state,” wrote historian Sergei Belyakov of the Urals Federal University in his article ‘Falsifying Eurasianism’.

Although their historical theories were unproven, the Eurasianists were successful academics in their subject areas: Prince Nikolai Trubetskoi and Roman Jakobson, for example, stood the frontier of structural linguistics.

But Dugin is sceptical of the value of scientific knowledge. “Science is just a modern kind of mythology,” he has written.

And apart from his rejection of the West, he has very little in common with the Eurasianists. The thinker has proselytised ‘Russian national-socialism’ and ‘Russian fascism’ as the means to establish a ‘Russian order of things’.

He founded the National-Bolshevik Party along with the author Eduard Limonov, unifying far left and far right ideas as an alternative to the official liberalism of the Yeltsin years.

In 1995, Dugin was a candidate for the Russian Parliament, the State Duma, from the National-Bolsheviks, endorsed by the musician Sergei Kurekhin, known for his absurdist projects, the most famous of which was called ‘Lenin-fungus’.

The campaign was an utter disaster, Kurekhin died the following year, and in 1998 Dugin left the party.

But the 2010s saw the revanche of the thereto ‘untouchable’ ideologues in Moscow. Indeed, the Russian authorities themselves started speaking the language of Limonov, Dugin and his friend, the writer Alexander Prokhanov. They demanded restitution for the humiliation of the 1990s, declared that Crimea and northern Kazakhstan were Russian lands, considered liberalism the root of all evil, and concocted a cult of Stalin and Orthodox Christianity.

Nobody knows precisely why after 2014 people began to call Dugin Putin’s ideologue and the Kremlin’s guru. Perhaps it’s because, more than anyone else, he claimed such a role by remaining in permanent orbit around Kremlin projects.

But according to the historian Torbakov, in truth he was only ever close to power at the end of the 1990s and early 2000s, when he occupied the post of advisor to the Duma speaker, Gennady Seleznyov.

‘The problem of Ukrainian sovereignty’

Dugin’s most famous book, ‘The Principles of Geopolitics’, came out in 1997. He presents the world as a struggle between land-based and marine civilisations – with the former represented by the Eurasian world, led by Russia, and the latter – the Atlantic world, headed by the United States.

In Eurasian states, according to Dugin, power has traditionally been authoritarian and society based on collectivism. Democracy, individualism and enterprise – that’s all for the Atlantic world. Meanwhile, behind the scenes, there’s a struggle between the ‘order of Eurasianists’ and the ‘order of Atlanticists’ – between, as it were, the mega-secret services of both.

This particular conspiracy theory is perhaps Dugin’s favourite. He has called the GRU – the Russian military intelligence agency – ‘Eurasianist’, while dubbing the KGB ‘Atlanticist’. The struggle between them, he traces to the Nazis: senior SS official Reinhard Heydrich was an agent of the Eurasians, and his assassination was the work of a secret Atlanticist, Wilhelm Canaris, rather than that of Czech partisans.

The book also contains some of his youthful enthusiasms, such as a study of war between Nordic and Southern races who emerged from the ancient continents of Hyperboria and Gondwanaland. He borrowed the idea from Hermann Wirth, the first head of the Nazi centre for the study of Nordic races. Later on, he returns to his ‘Pamyat’ antisemitism, and writes about a struggle between white peoples and “moonish Semites, Judeans and Saracens.”

“There’s nothing coincidental about the conspirology-based antisemitism in Dugin’s thinking,” according to Viktor Shnirelman, senior research fellow at the Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology of the Russian Academy of Sciences. It’s connected, he says, to the popular idea of the 1990s that ‘world Jewry’ was to blame for the collapse of the USSR.

“The Principles of Geopolitics” found an audience among hardliners in power. It was on the reading list at the Military Academy of the Russian General Staff, where the philosopher himself taught, conducted research, and lectured. The textbook on geopolitics recommended by the Russian education ministry also quotes him at length.

Dugin has often changed his ideas, and sometimes distanced himself from his former thinking. But he has been more consistent on some questions not only than Russia’s authorities, but also the far right radicals – for example, in stoking fear of an independent Ukraine.

In his book, he called Ukraine’s independence an existential threat to Russia. He suggested establishing control by Moscow over south-eastern Ukraine and Crimea, though not annexation.

In his less serious works, Dugin didn’t shy away from down-home Ukrainophobia and suitably insulting epithets.

And, just like Vladimir Putin at present, Dugin saw in Ukraine an instrument of the struggle of the US against Russia. He wrote: “The existence of a ‘sovereign Ukraine’, at the geopolitical level, is a declaration of geopolitical war against Russia (and it’s more about Atlanticism and Sea Power than about Ukraine).”

Torbakov says this doesn’t mean the philosopher has influenced Russia’s government or Putin personally: “There’s a huge reservoir of conservative ideas, including anti-Ukrainian ones – that the Kremlin can draw upon at will.”

He points out that Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s political essay of 1990 – ‘Rebuilding Russia’ – contains many of the things that Putin would come to repeat. In the essay, the author described the independence of Ukraine and Belarus as a tragedy to be avoided. He considered the Ukrainian language to be an Austro-Hungarian confection and “stuffed with German and Polish words.”

“Kill, kill, and kill again”

Torbakov says that when Seleznyov quit the speaker’s post in the Duma, Dugin lost access to the corridors of power. But he got a second chance after the 2004 ‘Orange Revolution’ in Kyiv. Dugin promptly formed the Union of Eurasianist Youth to fight back against the protests. And the fight was conducted by the deputy head of the Presidential Administration, Vladislav Surkov.

“The project was set up to meet the needs of the administration, and we got Eurasianism into it. We used the Presidential Administration – and they, and Surkov, used us right back,” wrote Pavel Zarifullin, a former colleague of Dugin’s.

Along with his comrades, in 2008, Dugin gathered an ‘anti-fascist conference’ at the state news agency, RIA Novosti, devoting it to attacks on Ukraine and the Baltic states. It was a lot like a similar congress held in August this year by Sergei Shoigu, the Russian minister of defence.

“We need to ask ourselves if it is in our interests that the state of Ukraine exists”, repeated Dugin once more.

But by the end of the decade, the Eurasianist project had lost the support of the authorities and Dugin took up an academic career. From 2008-14, he was a professor at the sociology faculty at Moscow State University, and from 2012 became a member of the expert council of the then Duma speaker, Sergei Naryshkin.

The press started to talk of him as the informal advisor and ideologue of the ruling ‘United Russia’ party, which had taken a turn towards conservatism. Dugin was invited to prestigious philosophical conferences at which he backed up his political projects with quotes from Martin Heidegger, and the German philosopher’s concept of ‘Dasein’ – ‘immanence’ or ‘being’.

He also began to show up on state television, where at times he engaged in plain trolling. He called for the internet to be banned, and described beard-wearing as a “fundamental virtue of Russian Orthodox men” – and the absence of a beard, symbolic castration.

Dugin is also said to have coined the phrase ‘All the good guys are Russians’.

As he became a meme, Dugin gained a mass audience. Intrigued by the troll-philosopher, a new generation opened for themselves his essays and pop music from the 2000s in which he claimed to uncover the deeper meaning of things. For example, he heard in the songs of pop star Tatiana Bulanova ‘the whining cry of the final depths’, while in the lyrics of Konstantin Meladze could be found new testaments and sacred revelations.

His fans and haters argued whether he was being serious or just having fun. His friendship with Kurekhin, author of so many mystifications, leaves little doubt about the nature of his sayings.

His academic career and popular trolling came to an end in 2014 with the annexation of Crimea and war in the Donbas.

Dugin came out as one of the most active supporters of the idea of ‘Novorossiya’ and the further annexation of Ukrainian territory. His call to “kill, kill and kill again” representatives of Ukraine’s government provoked protest in Russia and he was sacked from Moscow State University.

“There are books, but Putin doesn’t read them”

But the important thing isn’t that he was criticised in society, in Torbakov’s opinion, but that he was getting ahead of the Kremlin: “He reached his peak in 2014, but soon lost his academic position and access to television. He had become unacceptable in the eyes of the presidential administration.”

“After 2014, my contact with the Kremlin was sharply reduced,” he said in an interview with Prokhanov’s newspaper, ‘Tomorrow’. “I have to say, I’m pretty disappointed in Putin,” he added, accusing him of squandering the ‘Russian Spring’.

Still, the Russian elite remained happy to avail themselves of Dugin’s services. Between 2016-17, he worked as the editor-in-chief of the ‘Tsargrad’ TV channel owned by the ‘Orthodox Businessman’ Konstantin Malofeyev, who sponsored cooperation with far right movements in Europe and the US. Dugin remained popular among European rightists and traditionalists.

He maintained contact with academic and ideological groups in China, Iran and Turkey – countries with a strong anti-western sentiment, notes Torbakov.

The Turkish politician and ideologue Doğu Perinçek, seen as an informal advisor to President Erdogan, called Dugin and his family ‘friends of Turkey’. Local media have speculated that the connection between Perinçek and Dugin may have had a hand in the closer relationship between Turkey and Russia from 2016.

Perinçek claims that it was Dugin himself who warned Erdogan’s advisors of the coup being prepared against him on July 14th 2016. So far, there has been no proof of this.

The nearness of the thinker to power in Russia is hugely exaggerated, Torbakov believes. “The op-eds calling Dugin ‘Putin’s Brain’ drive me crazy.”

Dugin, meanwhile, complained in 2020 that Putin is not adopting the right ideas: “There are books, but Putin doesn’t read them, though he ought to. Or maybe he reads them but doesn’t understand them. Or maybe he just flicks through them.”

The BBC sought comment from Dugin through the press service of the International Eurasianist Movement. We received no response at the time the article was published.

Translated by Chris Booth.

Read this story in Russian here.